Urban sustainability refers to a city’s ability to meet current needs while preserving the environment, resources, and quality of life for future generations. Numerous interconnected environmental, social, and economic challenges complicate efforts to achieve sustainability in modern urban areas.

Resource Scarcity and Environmental Strain

Limited Natural Resources

One of the central challenges to urban sustainability is the limited availability of essential natural resources. As cities grow, they require increasing amounts of freshwater, land, and energy. This demand often surpasses the local supply, requiring cities to source resources from distant regions, increasing environmental costs.

Water scarcity becomes critical in arid regions or densely populated cities. Overuse of water resources can deplete aquifers and harm ecosystems.

Energy consumption in urban areas is intense, often relying on fossil fuels. This dependence increases greenhouse gas emissions and air pollution.

Land scarcity forces development onto marginal lands, resulting in the destruction of green spaces, wetlands, and farmland. This affects local biodiversity and contributes to ecological degradation.

As cities expand, the strain on these resources intensifies, making sustainability more difficult to achieve without systemic reforms in resource management and conservation strategies.

Pollution and Environmental Degradation

Urban areas are significant sources of pollution, contributing to the degradation of air, water, and soil quality. These forms of pollution impact public health and degrade the environment.

Air pollution is driven by vehicular emissions, industrial activities, and construction. Pollutants like nitrogen oxides, sulfur dioxide, and particulate matter can cause respiratory problems and contribute to climate change.

Water pollution results from sewage discharge, industrial runoff, and stormwater pollution. Contaminated water sources spread disease and disrupt aquatic ecosystems.

Soil contamination can arise from improper waste disposal, industrial waste, and leaking underground storage tanks. Contaminated soil is dangerous for human health and agricultural use.

Urban pollution also accelerates climate change, intensifying environmental vulnerabilities and making long-term sustainability harder to achieve.

Land Use and Urban Expansion

Suburban Sprawl

Suburban sprawl, or suburbanization, refers to the outward expansion of urban areas into rural and undeveloped lands. This process creates low-density, car-dependent communities that present numerous sustainability issues:

Increased reliance on automobiles results in higher fuel consumption, greenhouse gas emissions, and traffic congestion.

Loss of farmland and forests disrupts ecosystems and reduces biodiversity.

The development pattern encourages placelessness, where suburban areas become indistinguishable due to standardized commercial developments and repetitive architecture.

Sprawl also reduces efficiency in public service delivery, requiring more roads, utilities, and emergency services per capita than dense urban areas.

Brownfields and Redevelopment

Brownfields are abandoned or underused industrial or commercial sites where redevelopment is complicated by real or perceived contamination. These sites often contain hazardous substances, making cleanup and reuse challenging.

Cleanup and remediation of brownfields require environmental assessments, soil testing, and removal or treatment of contaminants.

Regulatory hurdles can delay projects, as governments must ensure health and environmental standards are met.

Financial barriers can discourage investment, although grants and tax incentives can encourage redevelopment.

Despite the difficulties, successful brownfield projects can revitalize urban areas, provide new housing and jobs, and reduce urban sprawl by repurposing existing land instead of developing greenfield sites.

Social Inequality and Informal Settlements

Poverty and Inequity

Urban areas often exhibit stark socioeconomic inequalities, with wealthy neighborhoods existing alongside impoverished ones. Disparities in income, education, and access to services create significant challenges for urban sustainability:

Residents of low-income areas may lack access to public transportation, quality healthcare, and safe housing.

Environmental injustices occur when marginalized communities are disproportionately exposed to pollution and environmental hazards.

These inequalities can lead to social unrest, reduce quality of life, and hinder cohesive community development.

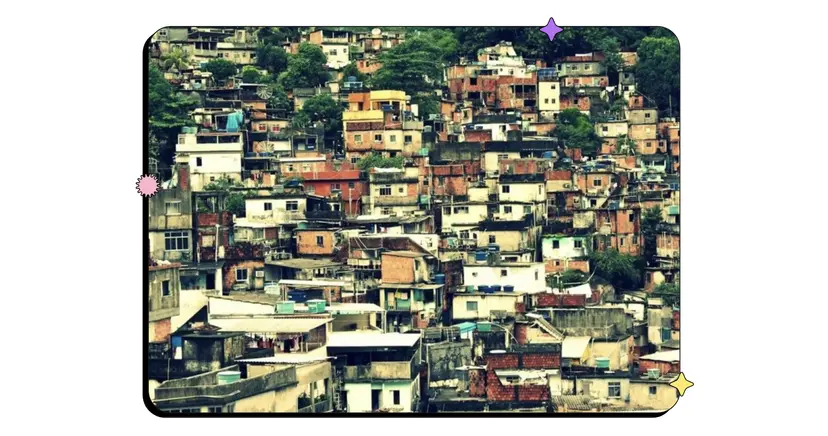

Squatter Settlements and Shantytowns

In rapidly urbanizing countries, many people settle in informal housing areas due to the lack of affordable formal housing. These areas, often called squatter settlements or shantytowns, are built without legal permission on land the residents do not own.

Favelas (Brazil), barriadas (Peru), and slums in other regions represent these settlements.

Housing is often constructed from scrap materials, such as tin, plastic, and wood.

Access to clean water, sanitation, electricity, and waste disposal is often limited or nonexistent.

These settlements are frequently located in vulnerable areas, such as floodplains or steep hillsides, where natural disasters can be catastrophic.

Source: Latin America Bureau

Global Examples of Squatter Settlements

Kibera, Nairobi, Kenya: One of Africa’s largest slums, known for poverty, overcrowding, and minimal infrastructure.

Orangi Town, Karachi, Pakistan: A massive informal settlement with over one million residents, many without access to basic services.

Dharavi, Mumbai, India: Famous for its dense population and informal economy, but also a hub of small-scale industries.

Neza-Chalco-Itza, Mexico City, Mexico: A sprawling settlement characterized by a lack of infrastructure, high pollution, and informal economies.

Residents often work in the informal economy, earning income from unregulated jobs like street vending or informal manufacturing. These jobs often lack labor protections and health benefits.

Transportation and Infrastructure

Traffic Congestion

Urban sustainability is deeply affected by the overwhelming use of private vehicles, which contributes to:

Traffic congestion, increasing commute times and reducing productivity.

Elevated air pollution, particularly carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides, and fine particulates.

Greater urban sprawl, as people live farther from work due to cheaper housing in suburbs.

Encouraging public transportation, cycling, and pedestrian infrastructure can help reduce emissions and improve quality of life.

Inadequate Sanitation

In many urban areas, especially in the Global South, infrastructure for sanitation and waste management is underdeveloped or entirely absent.

Poor sanitation leads to outbreaks of waterborne diseases like cholera and typhoid.

Inadequate waste disposal contributes to polluted rivers, blocked drainage, and worsening flood conditions.

Informal settlements are especially vulnerable due to the absence of formal sewage systems.

Improving sanitation requires significant investment in infrastructure, effective policy implementation, and community education.

Cultural and Psychological Dimensions

Placelessness vs. Sense of Place

The phenomenon of placelessness results from standardized urban development that erodes local identity. Common features include:

Strip malls with the same chain stores across different cities.

Identical suburban housing developments lacking architectural uniqueness.

This stands in contrast to a sense of place, which refers to people’s emotional and cultural connection to a location. A strong sense of place:

Encourages community engagement and civic participation.

Enhances mental well-being and social cohesion.

Reflects local culture, history, and shared experiences.

Efforts like placemaking aim to create distinctive, welcoming public spaces that reflect the character of the community.

Community Engagement

Cities that empower residents to participate in planning processes benefit from greater public trust and sustainable outcomes. Community-driven projects, such as:

Urban gardens

Neighborhood cleanups

Local markets

...can reduce pollution, increase green space, and foster a sense of ownership and pride in urban environments.

Climate and Natural Hazards

Vulnerability to Environmental Catastrophes

Poor urban planning and informal housing developments leave many city residents vulnerable to natural disasters:

Flooding is worsened by poor drainage and the paving over of natural floodplains.

Earthquakes devastate shantytowns with no building codes or structural integrity.

Tsunamis and hurricanes wreak havoc on coastal slums with little emergency preparedness.

Disaster impacts are especially severe in fragile settlements, where homes are made of weak materials and emergency services are lacking.

Climate Change Effects

Climate change exacerbates many urban challenges. Common impacts include:

Urban heat islands, where paved surfaces retain heat, raising city temperatures by 1 to 7 degrees Fahrenheit.

Intense rainfall events, overwhelming drainage systems and causing floods.

Prolonged droughts, threatening water supply and sanitation systems.

Cities must adapt through green infrastructure (such as green roofs and urban forests), water conservation, and resilient building codes.

Governance and Policy Challenges

Regulatory Complexity

Urban sustainability requires coordination across multiple government levels:

Local governments manage zoning, transportation, and sanitation.

National governments oversee environmental regulations and infrastructure funding.

Conflicting interests among stakeholders—developers, citizens, and politicians—can stall sustainability initiatives.

Fragmented governance leads to inefficiencies, delays, and policy gaps that make long-term planning difficult.

Political Will and Resource Allocation

Many sustainability efforts falter due to insufficient political commitment or resource allocation:

Short-term economic goals often override long-term environmental concerns.

Corruption or mismanagement can divert resources from critical projects.

Vulnerable populations may be excluded from decision-making processes.

Sustainability depends on governments prioritizing inclusive urban policies, transparent planning, and community engagement.

Farmland and Food Security

Encroachment on Agricultural Land

Urban expansion frequently consumes fertile agricultural land, impacting local food systems:

Longer supply chains increase carbon emissions and reduce food freshness.

Displaced farmers must move farther from markets, increasing production costs.

Loss of biodiversity occurs when forests and wetlands are cleared for development.

Protecting Green Spaces

Preserving green belts, community gardens, and urban parks offers:

Environmental benefits, including carbon sequestration and flood mitigation.

Health advantages, such as cleaner air and reduced stress.

Social equity, by ensuring all residents have access to nature.

Urban planning must balance growth with the protection of natural landscapes, ensuring sustainable access to food and clean environments.

Key Terms to Know

Brownfield: A contaminated site requiring cleanup before redevelopment.

Suburban Sprawl: Low-density development on city outskirts, reliant on cars.

Shantytown: Informal settlement with makeshift housing and limited services.

Placelessness: Homogenized landscapes lacking distinct cultural identity.

Disamenity Sector: Urban areas with poor infrastructure and low living standards.

Squatter Settlement: Unofficial housing on land without legal ownership.

Urban Heat Island: Area with elevated temperatures due to built environments.

Placemaking: Community-driven design of public spaces that reflect local identity.

Sense of Place: Emotional connection to a unique and meaningful environment.

Informal Economy: Unregulated jobs lacking legal protections or benefits.

FAQ

Environmental justice is a critical component of urban sustainability, especially in low-income neighborhoods that often bear the brunt of environmental degradation. These communities are disproportionately exposed to hazards like industrial pollution, waste disposal sites, and poor air quality. They frequently lack access to green spaces, clean water, and reliable public transportation. Environmental justice seeks to ensure equitable distribution of environmental benefits and burdens, which is essential for sustainable development. For urban sustainability to be truly effective, planning must prioritize these neighborhoods by:

Improving infrastructure and sanitation.

Remediating polluted sites.

Increasing access to parks and clean transit.

Including residents in decision-making processes.

Zoning laws significantly influence urban sustainability by regulating how land is used and developed within city limits. Poor zoning practices can exacerbate urban sprawl, increase traffic congestion, and segregate communities by income or race. However, smart zoning policies can:

Promote mixed-use development, reducing travel distances between homes, jobs, and services.

Encourage higher-density housing to preserve open space and farmland.

Designate green belts or conservation zones to prevent overdevelopment.

Support affordable housing to reduce inequality and commuting burdens.

Zoning reforms that prioritize sustainability create more efficient land use patterns and reduce the environmental impact of urban growth.

Technology plays an increasingly vital role in managing urban sustainability, especially in cities facing rapid growth and limited infrastructure. Smart city technologies help governments monitor, analyze, and optimize urban systems in real-time. Examples include:

Smart grids that improve energy efficiency by balancing supply and demand.

Traffic sensors and adaptive signal systems that reduce congestion and emissions.

GIS (Geographic Information Systems) for mapping informal settlements and planning infrastructure upgrades.

Waste management systems using sensors to optimize collection routes and reduce overflow.

Mobile applications that increase community participation and transparency in planning.

Technology enables data-driven solutions for cleaner, more efficient, and inclusive urban environments.

Cultural beliefs and traditions shape how communities engage with their environment and perceive urban development. In many cities, sustainability initiatives may conflict with local customs or values if not implemented sensitively. Key ways culture influences sustainability include:

Preferences for housing types (e.g., single-family homes vs. communal living).

Attitudes toward public vs. private transport.

The value placed on communal open spaces and religious or heritage sites.

Waste disposal and consumption habits influenced by traditional practices.

To be effective, sustainability plans must be culturally responsive, involving local communities and respecting traditions while promoting environmental goals. This fosters long-term success and public support.

The informal economy includes all economic activities not regulated by the state, and it plays a major role in many cities, especially in developing countries. Informal work—such as street vending, small-scale manufacturing, and waste collection—is often the primary income source for residents of informal settlements. Understanding the informal economy is essential for sustainability because:

It supports livelihoods and social stability in underserved areas.

Excluding it from planning leads to ineffective or harmful policies.

It presents opportunities for recycling, repair, and circular economy practices.

Informal workers can be partners in sustainable waste management and service provision. Recognizing and integrating this sector supports equity and efficiency in urban development.

Practice Questions

Explain two challenges that suburban sprawl poses to achieving urban sustainability.

Suburban sprawl creates sustainability challenges by increasing dependence on automobiles, which raises greenhouse gas emissions and contributes to air pollution. This car-centric development reduces transportation efficiency and worsens traffic congestion. Additionally, sprawl leads to the consumption of greenfield land, causing the loss of farmland and natural habitats. This land use change disrupts ecosystems, reduces biodiversity, and limits local food production. Both effects place strain on environmental systems and infrastructure, making it harder for urban areas to grow in ways that are socially equitable, environmentally friendly, and economically sustainable over the long term.

Describe how squatter settlements present both challenges and opportunities for urban planners.

Squatter settlements challenge urban planners by lacking formal infrastructure, resulting in poor sanitation, overcrowding, and vulnerability to natural hazards. These areas are often outside government regulation, complicating service provision and land rights enforcement. However, they also offer opportunities for inclusive development. Many contain strong community networks and informal economies that, if supported with public investment and legal recognition, can evolve into vibrant neighborhoods. Upgrading infrastructure, formalizing property rights, and involving residents in planning can transform these areas into sustainable communities, addressing social equity while improving environmental and living conditions within rapidly growing cities.