AP Syllabus focus:

‘Introduction to the concept of marginal relative frequencies, explaining how to calculate them as the row and column totals in a two-way (contingency) table divided by the grand total of all observations. Defining conditional relative frequency and demonstrating how to calculate it for specific parts of the contingency table, such as cell frequencies in a row divided by the total for that row, to explore relationships within subsets of the data. Essential Knowledge UNC-1.Q.1 and UNC-1.Q.2: Providing a clear guide on how to compute marginal and conditional relative frequencies from two-way tables, highlighting their importance in analyzing relationships between two categorical variables.’

Understanding marginal and conditional relative frequencies is essential for analyzing two categorical variables, revealing patterns and associations by comparing proportions rather than raw counts within a two-way table.

Calculating Marginal and Conditional Relative Frequencies

Marginal and conditional relative frequencies provide structured ways to examine relationships between two categorical variables, helping to determine whether the variables may be associated. These measures rely on proportions rather than raw values, making them central to interpreting two-way (contingency) tables in a meaningful statistical context.

Two-Way Tables and Observed Frequencies

A two-way table organizes data for two categorical variables by listing the categories of one variable in the rows and the categories of the second variable in the columns. Each cell in the table displays the frequency (count) of observations that fall into the corresponding row–column combination.

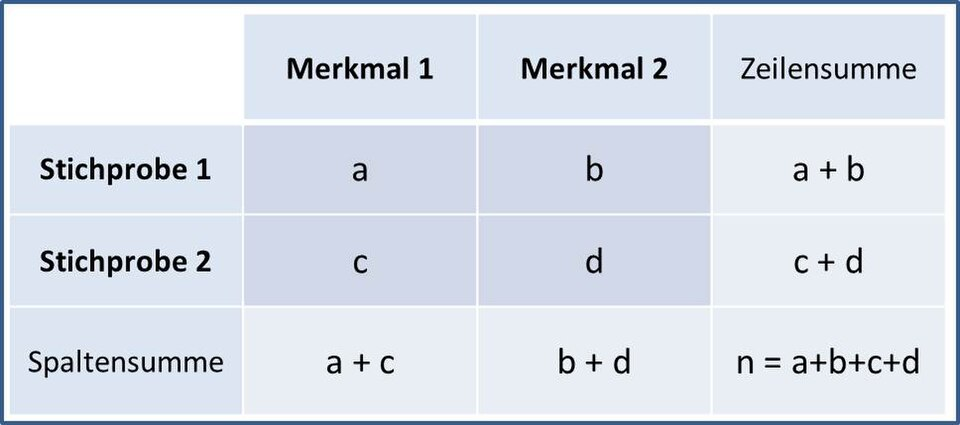

A 2×2 contingency table showing cell counts and marginal totals, illustrating the foundational structure used to compute joint, marginal, and conditional frequencies. German labels and references to the chi-square fourfold test appear but extend beyond the syllabus requirements while not affecting the table’s conceptual clarity. Source.

The totals along the margins are essential for computing relative frequencies.

Two-Way Table: A table that displays frequency counts for two categorical variables using rows and columns to show joint occurrences.

A two-way table contains three types of totals that play distinct roles: row totals, column totals, and the grand total. These allow for calculating proportions that describe how the data are distributed within and across variable categories.

Marginal Relative Frequencies

Marginal relative frequencies describe the proportion of the total number of observations that fall into each row category or each column category. They highlight how frequently each category appears in the overall dataset, regardless of the category of the other variable.

Marginal Relative Frequency: A proportion found by dividing a row total or column total by the grand total of all observations in a two-way table.

Marginal relative frequencies provide an overall view of each variable’s distribution, helping students compare category sizes and understand baseline proportions.

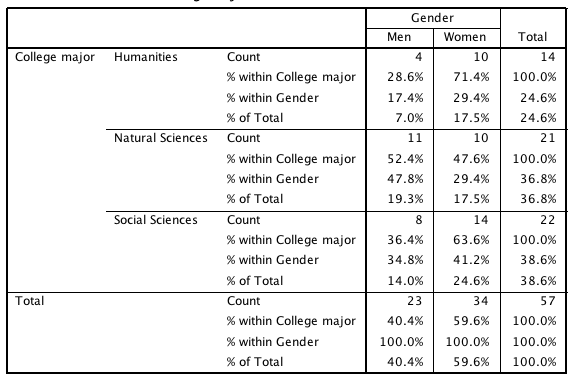

A contingency table displaying gender by major with percentages in each cell, illustrating how marginal totals and conditional distributions can be read directly from a two-way table. The specific majors and exact percentages extend slightly beyond the syllabus but faithfully represent the structural features needed for interpreting relative frequencies. Source.

Because they use the total number of observations as the denominator, they reflect broad patterns rather than conditional ones.

Conditional Relative Frequencies

Conditional relative frequencies offer more specific insight. A conditional relative frequency describes the proportion of observations that fall into a particular cell category, given that the observation belongs to a specific row or column. In other words, it restricts the comparison to a subset determined by one variable.

Conditional Relative Frequency: A proportion computed by dividing a cell frequency by the total for its row or column, representing the distribution of one variable within a fixed category of another variable.

These relative frequencies make it possible to analyze how the distribution of one variable differs across categories of the second variable. Conditional frequencies are essential for identifying potential associations, because differences in conditional distributions across categories may suggest that the variables are related.

How to Compute Marginal and Conditional Relative Frequencies

Organizing clean, clearly labeled two-way tables ensures that marginal and conditional relative frequencies can be calculated accurately and interpreted confidently. Students should follow a systematic approach when working with two-way categorical data.

Process for Marginal Relative Frequencies

Identify the row total or column total associated with the category of interest.

Locate the grand total, which is the sum of all cell frequencies in the table.

Compute the proportion using the formula:

Row marginal proportion = (row total) ÷ (grand total)

Column marginal proportion = (column total) ÷ (grand total)

Interpret the resulting proportion in the context of the variable alone.

Process for Conditional Relative Frequencies

Choose whether the condition is based on a row or a column.

Identify the total for that row or column.

Divide the relevant cell frequency by this row or column total.

Interpret the resulting proportion as describing the distribution of one variable within the category of the other variable.

Because conditional relative frequencies rely on a restricted total, they reveal within-group patterns that marginal relative frequencies cannot capture.

Interpreting Marginal and Conditional Relative Frequencies

Interpreting relative frequencies requires comparing proportions and considering how distributions differ across conditions. Marginal relative frequencies show overall category prevalence, while conditional relative frequencies reveal meaningful variation between subgroups.

Using Marginal Relative Frequencies for Insights

They allow comparisons of category sizes across the entire dataset.

They are necessary for establishing broad context before looking at associations.

They help identify imbalances or dominant categories in the data.

Using Conditional Relative Frequencies to Identify Associations

Differences across conditional distributions often suggest that variables may be associated.

Similar conditional distributions across categories typically suggest no association.

They provide the foundation for deeper statistical investigations, including later inference procedures.

By analyzing conditional relative frequencies, students gain insight into whether patterns observed in data are consistent with meaningful relationships or may simply reflect random variation.

FAQ

A joint relative frequency represents the proportion of observations that fall into a specific row–column combination out of the grand total. It focuses on a single cell in the context of the entire table.

A conditional relative frequency is calculated within a restricted group, using only the row or column total as the denominator. It reveals how one variable is distributed within a fixed category of the other variable.

When conditional relative frequencies differ noticeably across the categories of the explanatory variable, it suggests a potential association.

If the conditional distributions are very similar across categories, the variables are likely not associated. Statistical significance is not determined here, but patterns can guide further investigation.

Raw frequencies can mislead when groups differ in size, because larger groups naturally have larger counts.

Proportions standardise the data, enabling fair comparisons even when totals differ across rows or columns. This makes relative frequencies essential for interpreting relationships accurately.

Common errors include:

• Using the grand total instead of the row or column total.

• Misidentifying which variable is conditioned on.

• Confusing a difference in conditional frequencies with proof of causation.

Careful attention to the denominator and the wording of the condition reduces these mistakes.

These frequencies provide an early understanding of patterns in categorical data, allowing students to spot potential associations.

They also help build intuition about expected versus observed proportions, which becomes important when learning about chi-square tests and formal assessments of association later in the course.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

A school surveyed a group of students about whether they prefer studying in the morning or the evening. Out of all students surveyed, 120 preferred morning study and 80 preferred evening study. The total number of students surveyed was 200.

Calculate the marginal relative frequency of students who prefer morning study. Give your answer as a proportion.

Question 1 (1–3 marks total)

• Correct method: dividing 120 by 200 (1 mark).

• Correct numerical answer: 0.6 (1 mark).

• Correct statement that this represents the marginal relative frequency for morning study (1 mark).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

A group of adults were asked whether they drink tea regularly (Yes or No) and whether they prefer sweet or savoury snacks. Out of the 150 adults surveyed, 90 reported drinking tea regularly. Among the tea drinkers, 54 preferred sweet snacks and the rest preferred savoury snacks. Among the adults who do not drink tea regularly, 24 preferred sweet snacks and the rest preferred savoury snacks.

Using this information:

(a) Calculate the conditional relative frequency of preferring sweet snacks among tea drinkers.

(b) Calculate the conditional relative frequency of preferring sweet snacks among non–tea drinkers.

(c) Comment on whether snack preference appears to be associated with drinking tea.

Question 2 (4–6 marks total)

(a)

• Correct method for tea drinkers: dividing 54 by 90 (1 mark).

• Correct numerical result: 0.6 (1 mark).

(b)

• Correct method for non–tea drinkers: recognising that 60 adults do not drink tea (150 minus 90) and then dividing 24 by 60 (1 mark).

• Correct numerical result: 0.4 (1 mark).

(c)

• A correct comment noting that the conditional relative frequencies differ (0.6 vs 0.4), indicating a potential association between tea drinking and snack preference (1–2 marks depending on clarity).