AP Syllabus focus:

‘An overview of experiments in statistics, where treatments are deliberately assigned to subjects to observe their effects. Outline the process of creating a controlled experiment, including randomization and the assignment of treatments, to test hypotheses about cause-and-effect relationships.’

Experiments allow researchers to investigate cause-and-effect relationships by deliberately assigning treatments and controlling conditions. Proper design and implementation ensure reliable, unbiased results that support valid statistical conclusions.

Understanding Experiments in Statistics

An experiment is a statistical study in which researchers intentionally apply treatments to experimental units to measure resulting outcomes. Unlike observational studies, experiments allow for purposeful manipulation, enabling stronger causal claims when the design controls for confounding factors and random variation.

Experimental Unit: The individual or object to which a treatment is applied.

Experiments differ fundamentally from other data collection methods because of this deliberate intervention. This characteristic makes them uniquely powerful for answering questions about whether one variable causes changes in another.

Core Components of Experimental Design

Treatments and Explanatory Variables

A treatment is a specific condition applied to the experimental units, often defined by one or more explanatory variables (factors). Each factor may have multiple levels, and combinations of these levels create different treatments.

Treatment: A condition or set of conditions applied to experimental units in an experiment.

Clear identification of treatments is essential for linking observed outcomes to specific experimental conditions.

Response Variables

The response variable is the measured outcome used to assess the effect of the treatment. Properly defining the response variable ensures that results are interpretable, measurable, and aligned with the research objective.

Implementing a Controlled Experiment

Key Steps in Designing an Experiment

A well-implemented experiment follows structured, intentional steps designed to minimize bias and variability. These steps form the backbone of any controlled study.

Define the research question by identifying the causal relationship of interest.

Specify the explanatory variables, including factors and levels.

Determine treatments and how they will be assigned.

Select experimental units that are appropriate for testing the research question.

Plan the method of random assignment to distribute treatments impartially.

Establish protocols to ensure identical conditions across treatment groups except for the treatment applied.

Collect response data according to clearly defined measurement procedures.

Each step helps to maintain internal validity, ensuring that observed differences between groups can be attributed to the treatment rather than external influences.

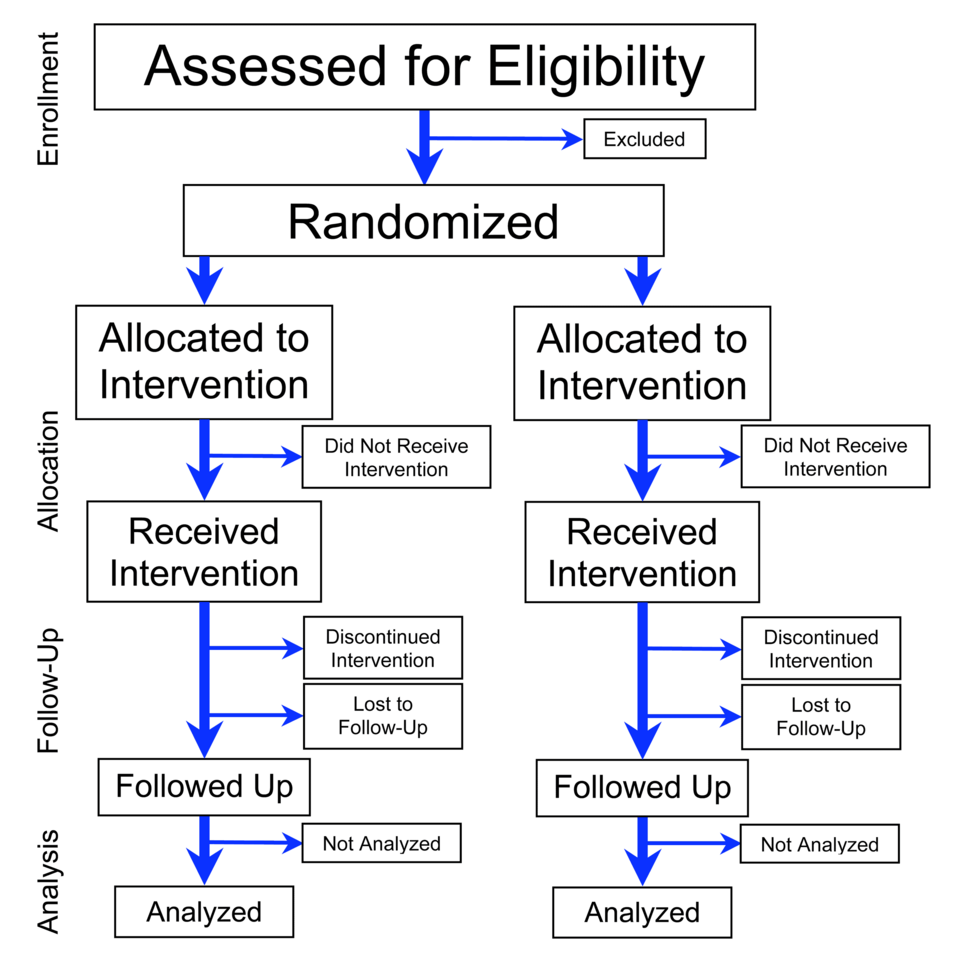

A typical experiment follows a pipeline of enrolling subjects, randomly assigning them to treatment or control groups, applying the treatments, and then measuring outcomes.

This flowchart illustrates the major phases of a randomized experiment: enrollment of subjects, random assignment to treatment or control groups, follow-up, and analysis. It highlights how randomization is embedded in a broader study design. The diagram contains some additional trial-reporting details beyond the AP syllabus, but they help show how real experiments are implemented and documented. Source.

Randomization: The Foundation of Causal Inference

Randomization is the process of assigning treatments to experimental units using a chance mechanism. Random assignment distributes uncontrolled variables roughly evenly across treatment groups, reducing the effect of potential confounders.

Random Assignment: The use of chance to assign treatments to experimental units, ensuring comparable groups.

Randomization does not eliminate variability but creates treatment groups that are similar on average, supporting valid comparisons that can reveal causal effects.

A normal sentence is placed here to maintain required spacing before introducing any additional structured content.

EQUATION

= Probability of a particular assignment

This probability framework underlies why random assignment protects against systematic bias: each possible assignment has an equal chance of occurring.

Controlling Experimental Conditions

Experiments must maintain consistent conditions across treatment groups to prevent external factors from influencing results. Researchers control the environment, timing, instructions, or measurement tools to isolate the effect of the treatment.

Consistent conditions support reliability by ensuring that any observed differences reflect treatment effects rather than external variation.

Replication

Replication refers to applying each treatment to multiple experimental units. Replication increases the reliability of results, reduces the influence of random variation, and supports more precise estimation of treatment effects.

Avoiding Confounding

A confounding variable is related to both the explanatory and response variables, making it difficult to determine whether observed effects are due to the treatment or the confounder.

Confounding Variable: A variable other than the explanatory variable that influences the response and may distort perceived relationships.

Proper control, random assignment, and consistent procedures help reduce confounding, strengthening causal claims.

Assignment Methods in Experiments

Completely Randomized Design

In a completely randomized design, all experimental units are pooled together, and treatments are assigned using a random process. This design is simple and widely used when units are relatively homogeneous.

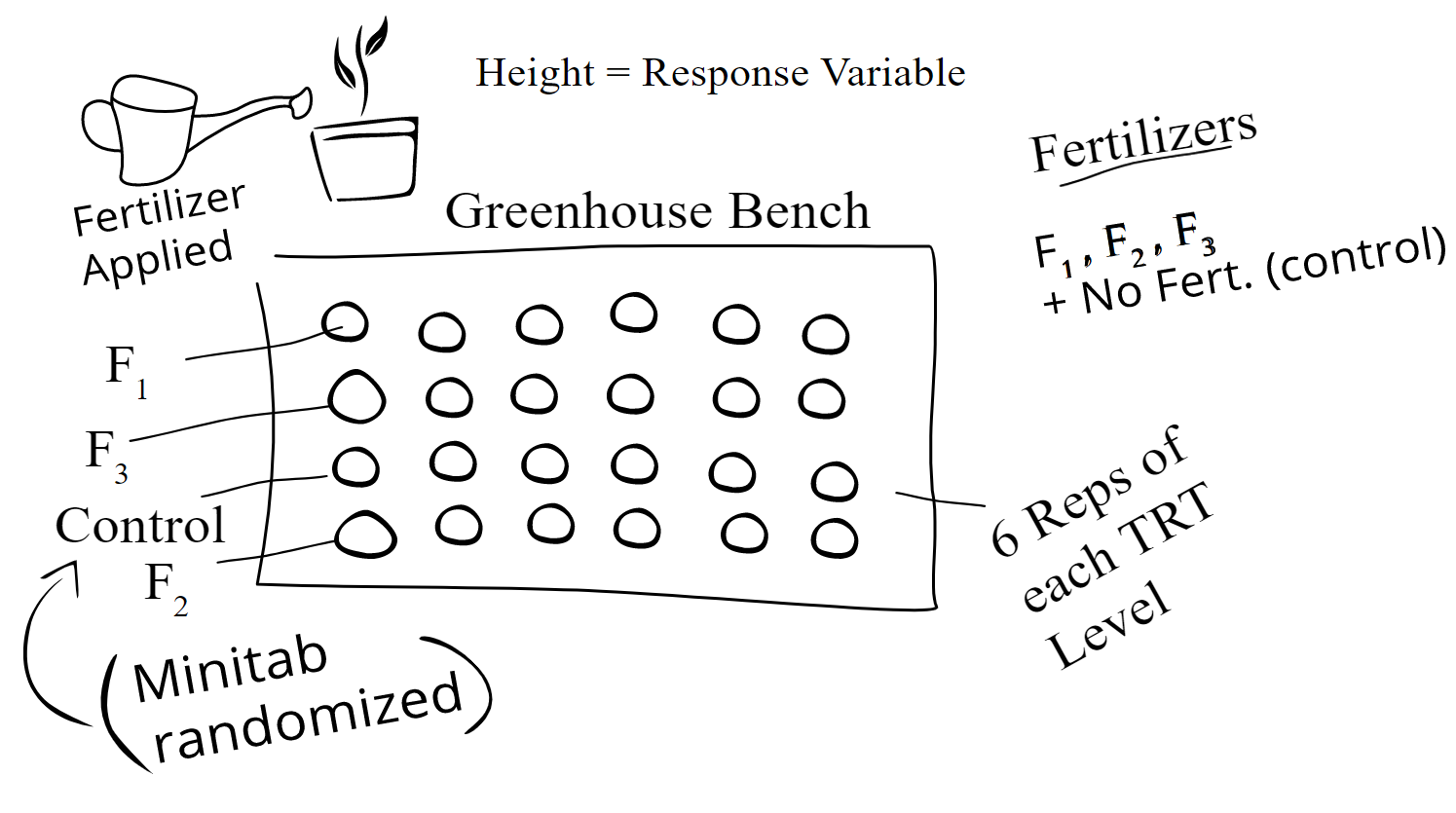

This schematic shows a greenhouse bench with 24 plants randomly assigned to four fertilizer treatments, including a control, with six replications each. It makes the roles of experimental units, treatments, and the response variable visually clear while emphasizing random assignment. Some notes about software (Minitab) and ANOVA extend beyond the AP syllabus but simply indicate practical ways experimental designs are generated and analyzed. Source.

Randomized Block Design

A randomized block design creates groups (blocks) of similar units before random assignment to treatments. Blocking reduces variability by ensuring that comparisons are made within more uniform groups.

Matched Pairs Design

A matched pairs design pairs units that are extremely similar or uses each individual as their own pair via two conditions measured in sequence. This design enhances precision by controlling for individual differences.

Executing the Experiment

During implementation, researchers must adhere strictly to the planned protocol. Consistency in delivering treatments, recording responses, and maintaining subject conditions is essential.

Follow standardized procedures for applying treatments.

Ensure blinding when possible to reduce psychological or measurement bias.

Monitor adherence to the plan to protect validity.

Record data uniformly to support accurate analysis.

Each step safeguards the experiment from influences that could undermine accurate interpretation of treatment effects.

FAQ

A treatment is well-defined when every participant receiving it experiences the same procedure, dosage, or condition. Vague or inconsistently applied treatments weaken the experiment because differences in outcomes may reflect inconsistencies rather than the treatment itself.

To ensure clarity:

Specify exact timings, quantities, or instructions.

Use standardised delivery methods.

Document procedures so they can be replicated.

Clear definition strengthens internal validity and allows meaningful comparisons between groups.

Researchers consider the purpose of the study and the practical limits of time, cost, and participant availability. Additional treatment levels help reveal patterns, but too many can dilute the sample size for each group.

A common approach is to:

Include a control group.

Use 2–4 treatment levels that capture meaningful differences.

Avoid unnecessary complexity unless examining a graded or multi-factor response.

The goal is to balance insight with statistical power.

Multiple factors are used when researchers want to understand how different variables interact or independently affect the response. This allows more efficient exploration of complex systems.

However, adding factors is appropriate only when:

The sample size is large enough to support multiple treatment combinations.

Interactions are plausible and of scientific interest.

The design can remain balanced and appropriately randomised.

Including extra factors without clear purpose can overcomplicate the design.

Maintaining identical conditions across treatment groups is challenging because real-world environments vary. Even small inconsistencies may introduce unwanted variability.

Common issues include:

Differences in timing or instructions delivered by multiple researchers.

Equipment variation, such as inconsistent calibration.

External influences like temperature, lighting, or noise.

Careful planning, training, and monitoring help reduce these inconsistencies.

Compliance is crucial because non-compliance blurs the distinction between treatment groups and weakens causal conclusions. Researchers use several strategies:

Clear explanations of the study’s purpose and procedures.

Regular check-ins or monitoring systems.

Incentives or reminders to encourage adherence.

Simple, easy-to-follow instructions to reduce participant burden.

High compliance helps ensure observed effects genuinely reflect the treatment.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

A researcher wants to test whether a new revision app improves students’ test scores. She randomly assigns 40 students to either use the app or not use the app for two weeks and then compares their test scores.

Explain why this study is an experiment rather than an observational study.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

• 1 mark: States that treatments are deliberately assigned to participants.

• 1 mark: Notes that random assignment is used.

• 1 mark: States that this deliberate assignment allows the researcher to test for cause-and-effect rather than simply observing existing differences.

Maximum: 3 marks.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

A team of nutrition scientists is investigating whether a high-protein breakfast increases concentration levels in teenagers. They recruit 60 volunteers from a local school and randomly assign each student to receive either a high-protein breakfast or a standard breakfast for one week. At the end of the week, each student completes the same concentration test.

(a) Identify the experimental units, the treatments, and the response variable.

(b) Explain why random assignment is essential in this study.

(c) Describe one additional feature of good experimental design the researchers should include, and explain how it strengthens the study.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Part (a)

• 1 mark: Identifies the experimental units as the 60 students.

• 1 mark: Identifies the treatments (high-protein breakfast and standard breakfast).

• 1 mark: Identifies the response variable as concentration test score.

Part (b)

• 1 mark: States that random assignment helps create comparable groups.

• 1 mark: Explains that it reduces the influence of confounding variables or systematic differences between groups.

Part (c)

• 1 mark: Names a valid feature of good design, such as replication, control of conditions, or blinding.

• 1 mark: Explains clearly how this feature strengthens the experiment (e.g., reduces variability, reduces bias, or improves internal validity).

Maximum: 6 marks.