AP Syllabus focus:

‘In-depth discussion on randomized complete block designs, blocking, and matched pairs designs. This will include the purpose of blocking to control for variability, the concept of matched pairs to closely compare treatments, and the application of these designs in experiments to improve the accuracy of conclusions.’

Advanced experimental designs refine basic experiments by controlling variability and improving comparison between treatments, allowing more precise, credible conclusions about cause-and-effect relationships in research settings.

Advanced Experimental Designs

In introductory experiments, we often simply compare treatment groups formed by complete random assignment. Advanced experimental designs go further by deliberately organizing experimental units to reduce unexplained variability. Two especially important designs for AP Statistics are randomized complete block designs and matched pairs designs, both based on the powerful idea of blocking.

Blocking: Purpose and Logic

When researchers suspect that a known factor (such as age, prior knowledge, or machine type) strongly affects the response variable, they do not want that factor to hide or distort treatment effects. Instead of ignoring it, they group similar experimental units together and randomize treatments within those groups.

Blocking: Grouping experimental units into relatively homogeneous groups (blocks) based on a variable related to the response, then randomizing treatments separately within each block.

Blocking is used to control for variability due to differences between blocks, so that comparisons of treatments are made within similar groups rather than across very different units.

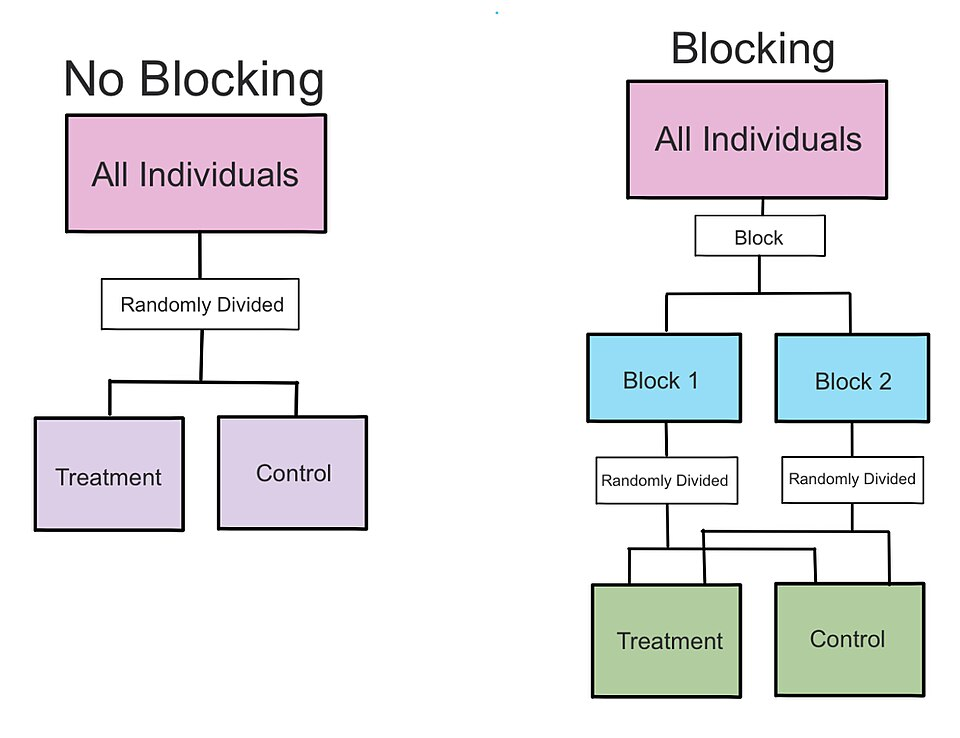

This diagram contrasts a non-blocked randomized design with a blocked design in which individuals are grouped into homogeneous blocks before randomization. It highlights how blocking restructures random assignment to control for known sources of variability. The framing elements simply provide general context without adding concepts beyond the syllabus. Source.

Randomized Complete Block Design (RCBD)

A randomized complete block design (RCBD) uses blocking in a systematic way whenever each block can receive all treatments being studied.

Randomized complete block design (RCBD): An experimental design in which experimental units are first grouped into blocks, and then all treatments are randomly assigned within each block so that every treatment appears in every block.

Key features of a randomized complete block design include:

Blocks formed first using a characteristic related to the response (for example, gender, class period, or field location).

All treatments represented in each block, allowing direct within-block comparisons.

Random assignment within blocks, not across the entire set of units.

Analysis based on within-block treatment comparisons, which reduces the influence of block-to-block differences.

A typical RCBD process:

Identify a lurking variable you can measure and use to define blocks.

Form blocks of units that are as similar as possible on that variable.

Within each block, randomly assign each treatment to one or more units.

Measure the response for all units and compare treatments within blocks.

RCBD is especially useful when:

Experimental units naturally fall into categories (such as different classrooms or production batches).

You believe between-block variation is large, but within-block variation is smaller.

You want fair treatment comparisons that do not depend on which block a unit belongs to.

However, RCBD requires that each block can reasonably receive every treatment and that block sizes align with the number of treatments. If blocks are poorly chosen or too small, blocking may not reduce variability and can even complicate the experiment unnecessarily.

Matched Pairs Designs

A matched pairs design is a special, very common case of blocking where each block contains exactly two “units” being compared as closely as possible.

Matched pairs design: A design in which experimental units are organized into pairs that are as similar as possible, or a single unit receives two treatments in random order, so comparisons are made within each pair.

Matched pairs designs appear in two main forms:

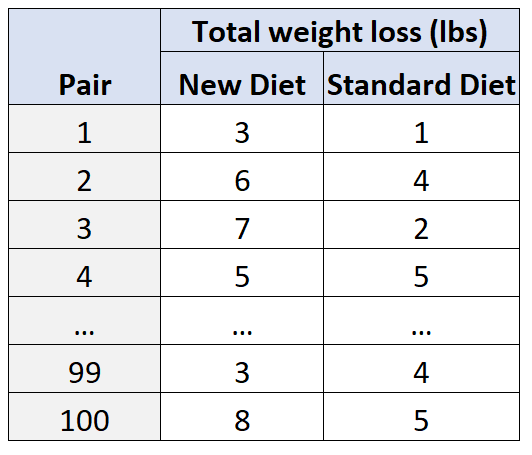

This table shows data from a matched pairs experiment in which each pair of similar subjects has outcomes recorded under two treatments. It emphasizes that conclusions rely on within-pair comparisons rather than differences between unrelated individuals. The large number of pairs shown is extra detail but does not introduce concepts beyond the syllabus. Source.

Two treatments on the same unit

One subject receives both treatments, often in random order (for example, two learning methods on the same student).

The “pair” consists of the two measurements on that single unit.

Two very similar units paired together

Two subjects are matched on key characteristics (such as age, prior score, or baseline health).

Within each pair, one subject is randomly assigned to each treatment.

A typical matched pairs process:

Decide which characteristics are important for making fair comparisons.

Either measure each subject twice (two treatments per subject) or form closely matched pairs of different subjects.

Randomly assign treatment order (for the same subject) or treatment labels (within each pair).

Focus on within-pair differences in the response to evaluate treatment effects.

Because comparisons are made within each pair, variability due to differences between subjects is greatly reduced, allowing more sensitive detection of treatment effects with relatively small sample sizes.

Blocking, RCBD, and Matched Pairs: How They Relate

Both RCBD and matched pairs are based on the same foundational idea: treat similar experimental units as a block and randomize treatments within that block. In fact:

A matched pairs design can be viewed as an RCBD where each block (pair) contains exactly two experimental units or two measurements from one unit.

Both designs aim to control for confounding variables by keeping them nearly constant within blocks or pairs while varying only the treatment.

When deciding between these designs:

Use a randomized complete block design when you have a moderate to large number of units in each category (block) and every block can receive all treatments.

Use a matched pairs design when you can closely match units in pairs or measure each unit twice, and you want very direct, sensitive comparisons between two treatments.

By thoughtfully using blocking, randomized complete block designs, and matched pairs designs, experimenters can control variability, sharpen treatment comparisons, and improve the accuracy and credibility of their conclusions about cause-and-effect relationships.

FAQ

Blocking and matched pairing shift the focus to within-block or within-pair differences, meaning treatment effects are interpreted relative to each block or pair rather than the overall sample.

This can:

• highlight subtle treatment effects masked by overall variability

• reduce error terms in analysis, increasing precision

• require statistical methods that explicitly account for the block or pair structure, such as paired comparisons or block-adjusted estimators

Researchers choose a blocking variable when there is strong prior evidence or theoretical justification that it influences the response variable. This decision often comes from pilot studies, expert knowledge, or previous research in the same field.

A useful guideline is to select a variable that:

• creates groups that are internally similar but meaningfully different from one another

• is practical to measure before the experiment begins

• is not itself an explanatory variable being tested

Yes. Blocking can reduce effectiveness when blocks are chosen poorly or without enough evidence that the blocking variable influences the response.

Unhelpful blocking can:

• introduce unnecessary complexity in design and analysis

• reduce randomisation flexibility

• create very small blocks, limiting the number of treatments that can be assigned

In such cases, a completely randomised design may be more appropriate.

Matched pairs link individuals or measurements in pairs, meaning each pair forms its own small block. This forces comparisons to occur within pairs rather than across larger groups.

In contrast, two similar groups may still differ in subtle ways, and treatment differences can be confounded by between-group variation. Matched pairs remove this issue by tightly coupling each treatment comparison to a specific pair.

Repeated measures are preferred when the characteristic being controlled varies widely across individuals but remains stable within each person over time.

Using the same subject avoids difficulties in finding perfectly matched partners and ensures near-total control of subject-specific variability.

This approach is especially useful when:

• the response can be measured multiple times without long-term effects

• treatment order can be randomised

• carry-over effects can be minimised or accounted for

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

A researcher is testing two different fertiliser formulas on plant growth. She suspects that differences in sunlight exposure across the greenhouse could affect plant height. She divides the greenhouse into three zones based on sunlight level (low, medium, high), places several plants in each zone, and randomly assigns both fertiliser treatments within every zone.

a) Identify the experimental design used.

b) Explain why this design is appropriate for the researcher’s concerns.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

a) 1 mark

• Correctly identifies a randomised complete block design (or acceptable equivalent such as “blocking with randomisation within blocks”).

b) 1–2 marks

• 1 mark for stating that sunlight exposure is a potential source of variability that might affect plant height.

• 1 mark for explaining that blocking by sunlight levels and randomising treatments within each zone controls this variability, allowing fairer comparison of fertilisers.

Maximum: 3 marks

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

A sports scientist wants to compare two training programmes, Programme A and Programme B, to see which leads to greater improvements in running speed. Because athletes vary widely in age, baseline fitness, and experience, the researcher pairs athletes who are very similar on these characteristics. Within each pair, one athlete is randomly assigned to Programme A and the other to Programme B.

The study runs for eight weeks, after which the improvement in speed for each athlete is recorded.

a) Identify the experimental design used.

b) Explain how this design helps to control variability.

c) Give one reason why this design may provide more sensitive comparisons than a completely randomised experiment.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

a) 1 mark

• Identifies the design as a matched pairs design.

b) 1–2 marks

• 1 mark for explaining that pairing athletes on similar characteristics controls for differences in age, baseline fitness, or experience.

• 1 mark for stating that random assignment within each pair isolates the effect of the training programmes.

c) 1–3 marks

• 1 mark for stating that matched pairs reduce subject-to-subject variability.

• 1 mark for explaining that within-pair comparisons allow more precise detection of differences between programmes.

• 1 mark for noting that this often increases sensitivity or statistical power compared with a completely randomised design.

Maximum: 6 marks