AP Syllabus focus:

‘Enduring Understanding: VAR-3 highlights that well-designed experiments can establish evidence of causal relationships. This foundational concept underscores the importance of selecting an experimental design that can robustly test hypotheses and establish causality.’

Understanding experimental design is essential because the structure of an experiment determines whether researchers can make credible causal claims and reliably test hypotheses about relationships between variables.

Understanding Experimental Design

Experimental design refers to the overall plan used to structure an experiment so that cause-and-effect relationships can be investigated convincingly. A well-designed experiment uses deliberate structure and controls to isolate the effect of an explanatory variable on a response variable. This aligns directly with the syllabus emphasis that strong design is what allows researchers to establish evidence of causal relationships.

When an experiment is properly planned, the design ensures that the only systematic difference between groups is the treatment itself. This clarity is what enables researchers to attribute observed differences in outcomes to the treatment rather than to confounding influences.

Core Purpose of Experimental Design

A central priority in designing an experiment is establishing causality, introduced here as the ability to conclude that changes in one variable produce changes in another.

Causality: A relationship in which variation in an explanatory variable directly produces variation in a response variable.

Because observational studies cannot reliably eliminate confounding variables, experiments serve as the primary method for causal inference. Good design minimizes alternative explanations for observed effects.

The AP Statistics framework highlights this connection through Enduring Understanding VAR-3, which underscores that experiments must be built deliberately to yield trustworthy causal conclusions.

Key Structural Components

To create a valid experimental design, researchers must clearly identify the main components of the study. Each plays a role in ensuring clarity and reducing bias.

Explanatory and Response Variables

The explanatory variable is the factor manipulated by the researcher, and the response variable is the outcome measured after the treatment is applied.

Explanatory Variable: A variable intentionally changed or assigned in an experiment to study its effect on a response.

A clear statement of variables ensures the experiment directly tests the intended causal pathway.

Experimental Units and Treatments

Experimental units are individuals or objects receiving treatments. A treatment is a specific condition or level of the explanatory variable assigned to units.

These components must be aligned so that treatments are meaningful tests of the research question.

Principles Supporting Causal Claims

To fulfill the syllabus expectation of selecting designs capable of establishing causality, experiments rely on several foundational principles. These principles ensure that results are attributable to the treatment rather than to systematic differences among groups.

Random Assignment

Random assignment ensures each experimental unit has an equal chance of receiving any treatment.

Random Assignment: The use of a chance process to assign treatments to experimental units, creating groups that are comparable on average.

This mechanism distributes potential confounding variables evenly across groups, supporting valid causal inference.

Random assignment is distinct from random sampling; it does not make experiments generalizable to populations but instead strengthens internal validity.

Control

Control refers to methods used to reduce the influence of confounding variables or eliminate outside factors.

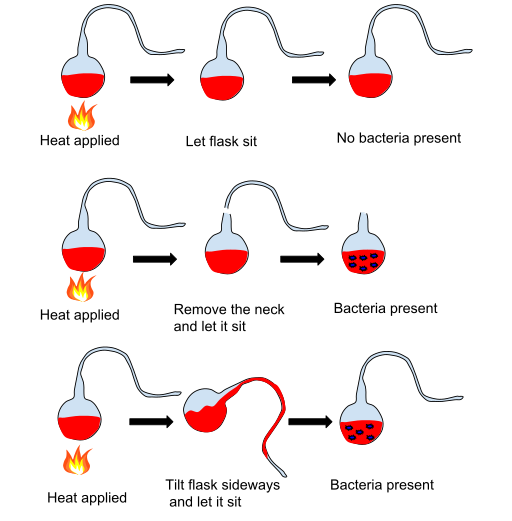

This diagram illustrates how a controlled experiment isolates the effect of a single factor by holding conditions constant across groups. Although microbiology-specific details are included, the visual clearly demonstrates the principle of control in experimental design. Source.

In an experiment evaluating treatment effects, all groups should be treated identically except for the treatment itself. This structural consistency supports clearer interpretation of outcomes.

Replication

Replication ensures enough experimental units per treatment group to distinguish real effects from natural variability.

Replication: The use of a sufficiently large number of experimental units to ensure that random variation is unlikely to distort treatment effects.

A large sample helps stabilize the influence of chance, increasing confidence in observed differences.

Designing for Internal Validity

Internal validity is the degree to which an experiment convincingly demonstrates a cause-and-effect relationship. A design with strong internal validity ensures that the treatment is the most plausible explanation for differences in the response variable.

To enhance internal validity, researchers typically incorporate:

Consistent procedures across treatment groups

Random assignment to eliminate systematic differences

Control of confounding variables, either through design choices or standardized conditions

Appropriate replication to reduce variability

These elements reinforce the syllabus emphasis on choosing an experimental design that “robustly tests hypotheses and establishes causality.”

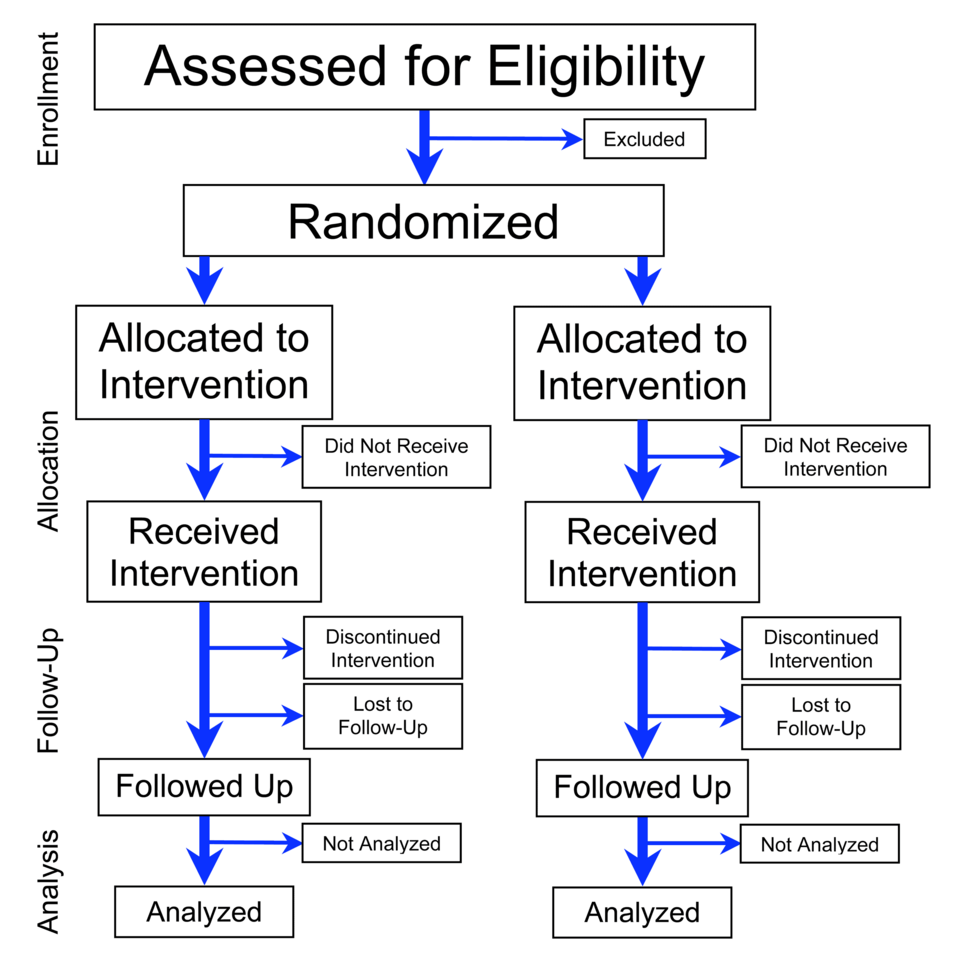

This flowchart demonstrates how randomized experiments assign units to treatment groups and track them through consistent stages, illustrating the structural logic that supports valid causal inference. Source.

Selecting an Appropriate Design

The AP focus on understanding experimental design includes recognizing that no single design fits all studies. Instead, researchers select a design that matches the research question, experimental units, and available resources. The goal is always to protect the ability to make a causal claim.

When choosing a design, researchers typically consider:

The number of factors and levels

Whether units differ meaningfully in ways that require blocking

The need for blinding to reduce response bias

The expected magnitude of variability among units

Practical limitations such as time, materials, and ethical considerations

Well-chosen designs reflect a deliberate effort to minimize confounding variables while isolating treatment effects.

Building Toward Causal Evidence

A strong understanding of experimental design equips students with the ability to evaluate whether a study’s structure allows credible causal conclusions. Every design decision—choice of treatments, assignment mechanism, control conditions, number of units—contributes directly to whether a causal relationship can be supported.

This subsubtopic therefore grounds students in the foundational idea that the power of experimentation comes not from data alone but from how the experiment is constructed.

FAQ

Blinding reduces the risk of behaviour changes that could blur treatment effects.

In single-blind designs, participants do not know which treatment they receive, limiting expectancy effects. In double-blind designs, researchers interacting with participants are also unaware of treatment assignments, reducing unintentional influence.

Blinding supports cleaner comparisons and decreases the chance that psychological or procedural differences contaminate the results.

While control focuses on removing or limiting confounding variables, standardisation ensures all experimental units undergo identical procedures apart from the treatment.

Standardisation may involve:

• Using the same instructions, timing, and equipment for all groups.

• Training researchers to follow consistent protocols.

• Ensuring environmental conditions remain stable across sessions.

Together, control and standardisation reinforce internal validity by eliminating unnecessary variation.

Internal validity concerns whether the experiment genuinely establishes a cause-and-effect relationship by ruling out alternative explanations. Reliability, by contrast, refers to the consistency of measurement tools or procedures across repeated observations.

A study may be reliable without being internally valid if the measurements are consistent but the design does not isolate the treatment effect. Conversely, even a well-designed experiment can suffer if unreliable measurement tools introduce noise into the data.

The number of treatment levels should balance meaningful scientific comparison with practical limitations.

Key considerations include:

• Whether additional levels provide genuinely informative contrasts.

• The risk of diluting sample sizes across too many groups.

• Resources required to administer and monitor each treatment.

• Whether the research question requires examining a trend or simply comparing two conditions.

A pilot study helps identify design flaws before running the full experiment.

Researchers might use a pilot to:

• Test measurement procedures to ensure they function correctly.

• Estimate variability in the response variable for better planning of sample sizes.

• Confirm that participants understand instructions or treatment protocols.

• Identify logistical issues that could undermine internal validity in the main experiment.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

A researcher wants to investigate whether a new revision technique improves students’ test performance. She randomly assigns 40 students to either use the new technique or use their usual study method.

Explain why random assignment is important in this experimental design.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

• 1 mark for stating that random assignment creates comparable groups on average.

• 1 mark for explaining that it helps distribute confounding variables evenly across groups.

• 1 mark for linking this to improved validity of conclusions about the effect of the revision technique.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

A nutrition scientist plans an experiment to determine whether increasing daily water intake affects concentration levels in adults. She identifies the explanatory variable, selects two treatment levels (1 litre per day and 2 litres per day), and measures concentration scores after two weeks.

(a) Identify the response variable in this experiment.

(b) Explain how control and replication should be incorporated into this design.

(c) Explain why this experiment, if well designed, can provide evidence for a causal relationship.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

(a)

• 1 mark: Identifying the response variable as the concentration score measured after two weeks.

(b)

• 1 mark: Explaining that control involves ensuring conditions are kept the same for both groups apart from the treatment (e.g., similar environment or instructions).

• 1 mark: Explaining that replication requires using a sufficiently large number of adults in each treatment group to reduce the impact of natural variability.

(c)

• 1 mark: Explaining that random assignment allows differences in concentration to be attributed to the treatment rather than to other variables.

• 1 mark: Stating that a well-designed experiment isolates the explanatory variable, supporting causal inference.