AP Syllabus focus:

‘VAR-3.D emphasizes the skill to explain why a particular experimental design is chosen over others. This involves assessing the experiment's objectives, the nature of the data, the available resources, and the characteristics of the experimental units to determine the most suitable design.’

Selecting the most suitable experimental design requires carefully aligning the study’s purpose, available resources, and characteristics of participants to ensure valid, interpretable, and meaningful causal conclusions.

Understanding Appropriateness in Experimental Design

Choosing an experimental design is fundamentally about match—the match between the research question, the type of data, and the constraints under which the study operates. Because experiments aim to establish cause-and-effect relationships, selecting an appropriate design directly affects the strength of the evidence that can be produced. AP Statistics students should recognize that appropriateness depends on how effectively a design supports random assignment, reduces variability, and isolates the effect of the explanatory variable.

Key Factors That Determine Design Appropriateness

Research Objectives and Hypotheses

A design must clearly support the goal of the study. If the objective is to compare multiple treatments, designs that accommodate comparisons—such as a completely randomized design—may be suitable. When the objective requires controlling for differences among experimental units, blocking or pairing may be necessary.

Nature of the Data

Researchers must consider:

Whether the response variable is quantitative or categorical

Whether variability across units may mask treatment effects

Whether measurements are repeated or occur only once

These considerations influence how treatments should be assigned and how experimental conditions should be structured.

Characteristics of Experimental Units

Experimental units are the individuals or objects receiving treatments. Their characteristics—such as age, background, baseline skill, or natural variability—directly affect design choices. For example, when units differ substantially, using blocking or a matched pairs design can help reduce unexplained variation.

Blocking: A technique that groups experimental units with similar characteristics to reduce variability in the response variable.

A design that ignores important differences among units may produce misleading results, even if random assignment is used.

A sentence must appear here to separate definition and upcoming structured content. Experimental appropriateness always depends on a balance between eliminating variability and maintaining feasibility.

Practical Constraints and Resources

Real-world experiments face limitations such as:

Time (e.g., long-term follow-up versus short-term testing)

Cost (e.g., number of units available, cost of materials)

Feasibility (e.g., ethical conditions, accessibility of subjects)

Researchers must select designs that function within these constraints while still maintaining integrity.

Major Experimental Designs and When They Are Appropriate

Completely Randomized Design

This design randomly assigns all experimental units to treatment groups without restrictions. It is appropriate when:

Units are similar in all relevant ways

No natural subgroups need controlling

Simplicity and clarity of treatment assignment are priorities

Use this design when variability among units is minimal, making random assignment sufficient to balance out unknown differences.

Randomized Block Design

This type of design incorporates blocks—groups of units with similar characteristics—to control for variability.

Block: A homogeneous group of experimental units formed to control for the influence of a specific variable.

Once units are placed into blocks, random assignment occurs within each block. This design is appropriate when one or more known characteristics strongly influence the response variable. It ensures comparisons between treatments occur among similar units, improving precision of estimates.

A normal sentence goes here to maintain separation before the next section. Blocking is especially appropriate in studies where environmental or personal factors cannot be eliminated but can be grouped.

Matched Pairs Design

A specific form of blocking, the matched pairs design pairs units based on shared characteristics or uses the same individual twice under different conditions. It is appropriate when:

Two treatments are being compared

Units can be matched closely or measured twice

Reducing variability within pairs enhances detection of treatment differences

Matched pairs help control for nearly all between-unit variability, isolating the treatment effect more clearly.

Factorial Designs

When researchers wish to study the effects of multiple explanatory variables simultaneously, factorial designs are appropriate. They allow measurement of both main effects and interaction effects, providing deeper understanding of complex systems. These designs are chosen when researchers seek efficiency or want to understand how variables work together.

How to Judge Whether a Design Is the “Right” One

Alignment With Study Purpose

A design is appropriate only if it directly supports the study's key question. For example, detecting subtle treatment effects requires designs that minimize variability, such as blocking.

Ability to Support Random Assignment

Appropriate designs preserve the central principle of experimentation: random assignment. If a design limits or complicates randomization in ways that introduce bias, it may be inappropriate.

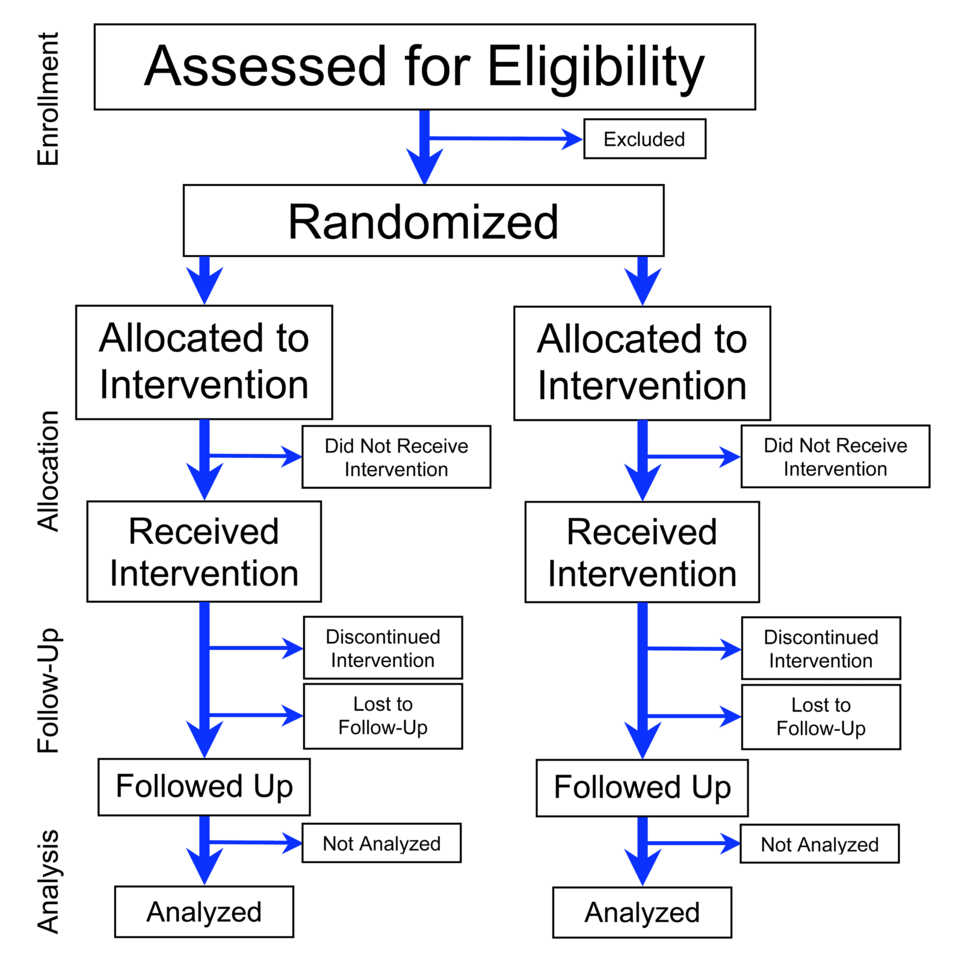

Flowchart of a parallel randomized experiment showing eligibility assessment, random assignment, treatment allocation, follow-up, and analysis. This illustrates how appropriate designs preserve clear treatment pathways and unbiased comparison between groups. The diagram includes more clinical detail than required for AP Statistics but effectively demonstrates overall experimental structure. Source.

Control of Confounding Variables

Appropriate designs anticipate and reduce confounding. Decisions such as blocking, matching, or adding control groups should directly address threats to validity.

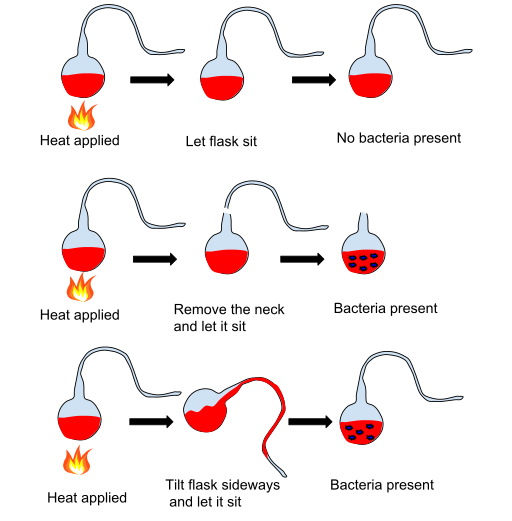

Diagram of Pasteur’s swan-neck flask experiment comparing different flask conditions to isolate the effect of airborne contaminants. This highlights how control conditions strengthen causal conclusions in experimental design. The image includes microbiology-specific details not required for AP Statistics but visually reinforces controlled comparison principles. Source.

Adaptation to Constraints

A theoretically strong design may be impractical. Appropriateness requires balancing rigor with feasibility, ensuring the design remains executable under real-world conditions.

Maintaining Integrity and Interpretability

A design is appropriate if it produces data that can be clearly analyzed and interpreted. Overly complex designs may obscure treatment effects, whereas overly simple ones may fail to control important sources of variation.

Putting It Together

Evaluating the appropriateness of experimental designs requires understanding how well a design aligns with the study’s objectives, characteristics of experimental units, resource constraints, and the need to support valid causal inference. The AP syllabus emphasizes that students must be able to justify why one design is chosen over another by considering these interconnected factors.

FAQ

The larger the number of experimental units, the greater the flexibility in choosing a design because random assignment becomes more effective at balancing characteristics across groups.

In smaller studies, designs that control variability more tightly, such as matched pairs or blocking, become more important because randomisation alone may not adequately balance key differences.

Researchers often choose simpler designs for large-scale studies to keep implementation manageable while maintaining statistical validity.

A matched pairs design is inappropriate when meaningful, measurable characteristics for pairing cannot be identified or when forced pairing introduces artificial similarities that do not reflect natural variation.

It is also unsuitable when the treatment cannot reasonably be applied twice to the same unit or when pairing would restrict the sample size excessively.

Matched pairing should only be used when it genuinely reduces variability without compromising the study’s feasibility.

Researchers typically select the characteristic most strongly related to the response variable, as controlling for the primary source of variation gives the greatest improvement in precision.

Additional considerations include:

Whether the characteristic is easy to measure reliably

Whether blocking on it avoids creating excessively small blocks

Whether the characteristic is stable and relevant for the entire duration of the study

Blocking decisions should balance statistical benefit with practicality.

When units are naturally clustered (such as patients within hospitals or students within classrooms), a completely randomised design can ignore important structural differences that influence results.

Clusters may have distinct environments, resources, or baseline characteristics that introduce confounding if not accounted for.

In such cases, designs incorporating blocking or hierarchical assignment are more appropriate because they respect the structure of the population.

Complex designs, while often offering better control of variability, typically require more resources in planning, implementation, and analysis.

Researchers must consider:

Time needed to measure blocking or matching variables

Costs associated with managing multiple design layers

Availability of personnel to administer treatments consistently

A simpler design may be chosen when resource constraints would undermine the reliability or completeness of a more complex approach.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks)

A researcher wants to compare two different teaching methods using a group of students who are similar in prior achievement. They are considering either a completely randomised design or a matched pairs design.

Explain why a matched pairs design may be more appropriate in this situation.

Question 1 (2 marks)

1 mark: States that matched pairs reduce variability or control for individual differences.

1 mark: Explains that students can be paired based on prior achievement or each student can act as their own control, making comparisons between teaching methods fairer or more precise.

Question 2 (5 marks)

A sports scientist wants to investigate whether three different hydration strategies affect athletes’ sprint times. The athletes vary widely in baseline fitness levels. The scientist is considering using either a completely randomised design or a randomised block design.

(a) State the key feature of a randomised block design. (1 mark)

(b) Explain why baseline fitness should be considered when choosing an appropriate design. (2 marks)

(c) Identify which design would be more appropriate in this study and justify your choice. (2 marks)

Question 2 (5 marks)

(a) 1 mark

States that participants are grouped into blocks of similar characteristics before random assignment takes place within each block.

(b) 2 marks

1 mark: States that fitness level could affect sprint performance independently of hydration strategy.

1 mark: Explains that failing to account for fitness differences would increase variability or confounding, making treatment effects harder to detect.

(c) 2 marks

1 mark: Identifies the randomised block design as more appropriate.

1 mark: Justifies that blocking on baseline fitness would reduce variability and allow more accurate comparisons between hydration strategies.