AP Syllabus focus:

‘UNC-3.A.2: Define a binomial random variable, X, as one that counts the number of successes in n repeated independent trials, with each trial having two possible outcomes: success or failure. Detail the criteria for a process to be considered binomial, including independence of trials, a fixed number of trials (n), only two outcomes per trial, and a constant probability of success (p) across trials.’

A binomial random variable provides a powerful framework for describing repeated chance situations, helping students link probability principles to structured processes involving repeated, independent trials.

Characteristics of Binomial Random Variables

A binomial random variable is a foundational concept in probability, capturing situations where repeated, chance-driven processes follow a consistent structure. To fully understand this type of random variable, students must be able to recognize when a real-world scenario meets the strict criteria that define binomial behavior. These criteria distinguish binomial settings from other random processes and ensure that binomial probability methods are applied correctly. In AP Statistics, the syllabus emphasizes that a binomial random variable counts the number of successes in a fixed number of repeated independent trials, each with only two possible outcomes and a constant probability of success.

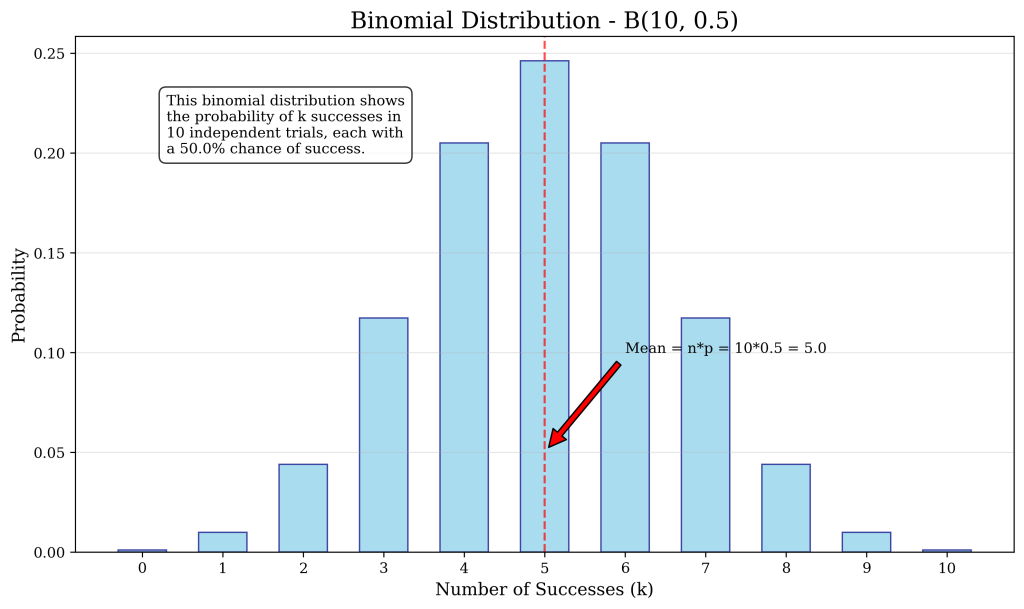

A bar chart displays the probability of each possible number of successes in 10 independent trials with constant probability of success, illustrating a binomial random variable as a count of successes. Source.

The Structure of Binomial Situations

In any binomial setting, each individual trial of the random process must result in one of two possible outcomes. The labels success and failure are conventional, but they do not imply desirability; they simply categorize the mutually exclusive outcomes of each trial. A trial refers to any single repetition of a random process, such as flipping a coin or testing a manufactured part. Binomial random variables, therefore, rely on predictably structured trials that produce clean, categorical results.

Binomial Random Variable: A random variable that counts the number of successes in a fixed number of independent trials, each with two possible outcomes and constant probability of success.

Each trial’s outcome must be unaffected by the outcomes of previous trials. This requirement of independence ensures that the probability model governing each trial remains stable throughout the process. Independence is essential; if earlier outcomes influence later ones, the process no longer fits the binomial framework.

Core Criteria for a Binomial Random Variable

The AP Statistics specification identifies four essential characteristics that must all be satisfied for a process to be binomial. These characteristics form a checklist that should be applied when evaluating situations involving repeated chance events.

A process is binomial only if all of the following conditions are met:

Fixed number of trials

The number of repetitions, denoted by n, must be predetermined and unchanging during the process. This fixed structure allows the random variable to measure countable outcomes from a known set of trials.Two mutually exclusive outcomes per trial

Every trial must result in a clear, non-overlapping outcome: success or failure. No other outcomes may exist in the context of each trial.Independence of trials

Each trial must operate separately from the others. The likelihood of success on Trial 1 must not affect or be affected by the likelihood of success on Trial 2.Constant probability of success

The probability of success, p, must remain the same across all trials. Similarly, the probability of failure, 1 − p, must also remain constant.

These four conditions work together to create the stable, predictable environment necessary for binomial modeling.

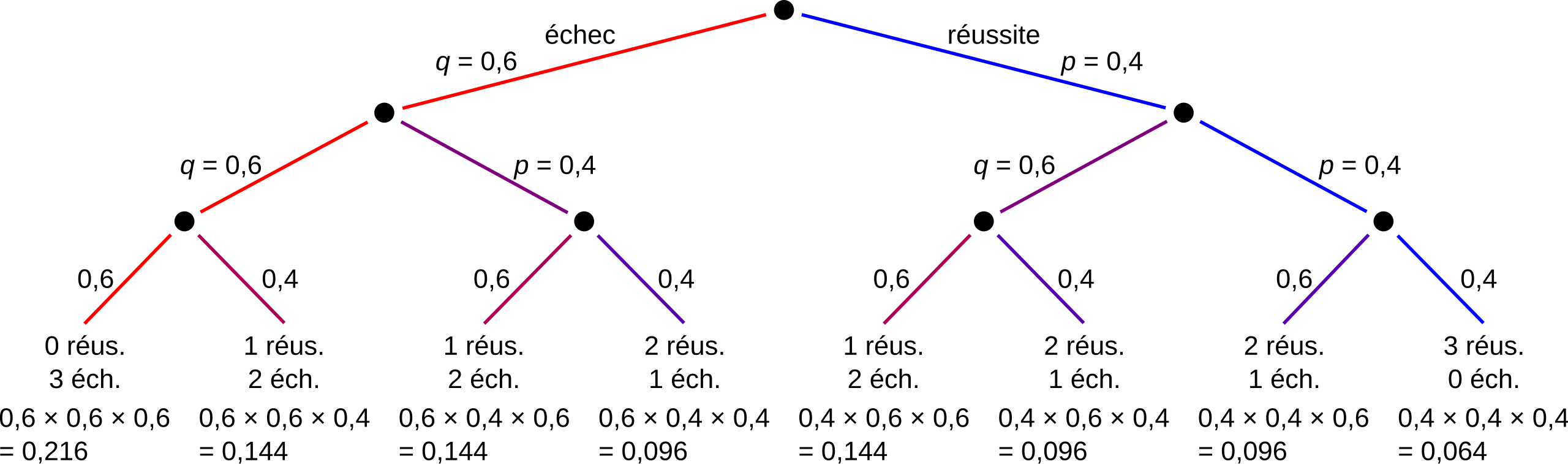

A probability tree illustrates three Bernoulli trials, each with fixed success and failure probabilities, emphasizing the independence and two-outcome structure required for a binomial setting. Source.

Understanding the Trial Structure

A binomial process focuses exclusively on the count of successes across multiple trials. Each trial behaves like a Bernoulli trial, which is a single experiment with only two outcomes and a constant probability of success. Thus, when multiple Bernoulli trials are combined, the count of successes becomes a binomial random variable. The stability of the Bernoulli structure across trials makes the binomial model mathematically consistent and interpretable.

Bernoulli Trial: A trial with exactly two possible outcomes—success or failure—and a constant probability of success.

Repeated Bernoulli trials form the backbone of binomial processes, and binomial random variables track how many successes occur in the entire collection of these trials.

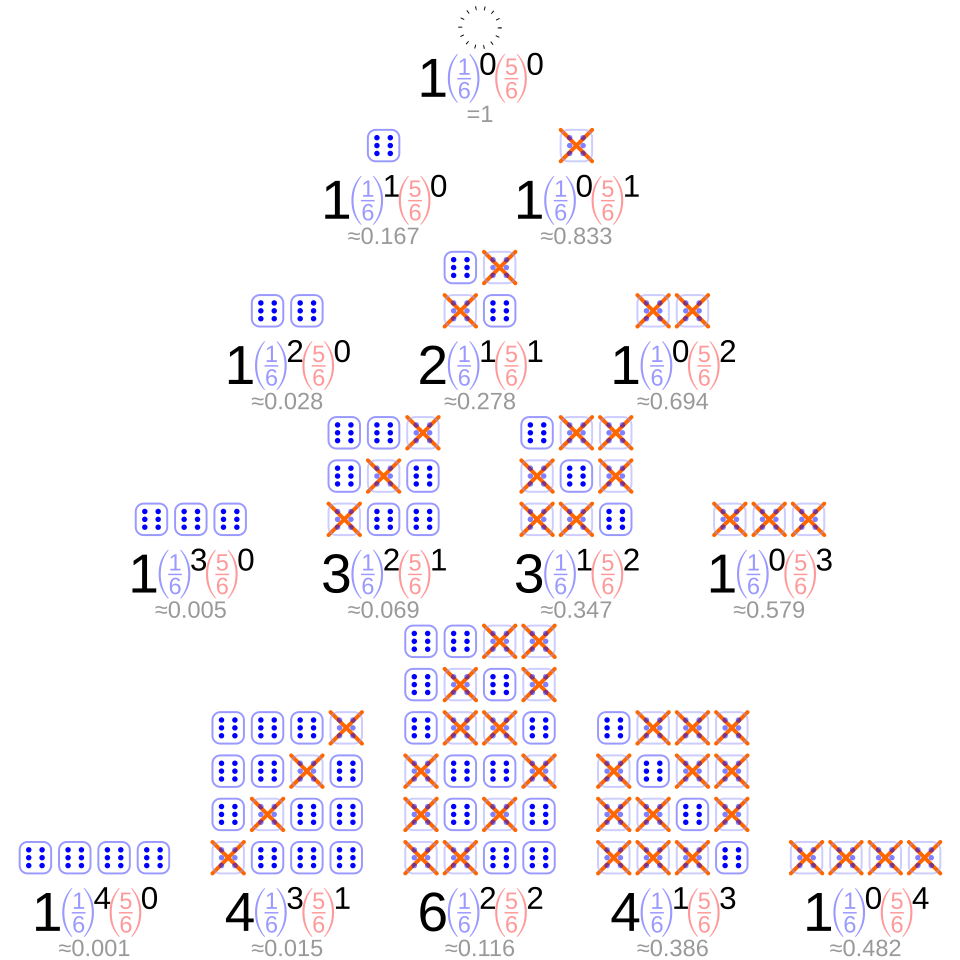

An array of dice highlights how successes and failures can be counted across identical independent trials, reinforcing the idea that a binomial random variable measures the number of successes in a fixed set of trials. Source.

Identifying Successes and Failures

One of the subtle but essential aspects of binomial modeling is the researcher’s ability to define success meaningfully for the context at hand. Success should be clearly stated and consistently identifiable. For example, success may mean a product passes inspection, a survey respondent answers “yes,” or a randomly selected individual displays a specific trait. Once defined, every trial in the process must adhere to that definition to maintain the binomial structure.

Recognizing Binomial Scenarios in Practice

Students must develop fluency in identifying binomial settings by applying the four defining criteria. Many real-world processes appear repetitive and binary but fail the criteria upon closer inspection. For instance, probabilities may shift over time, or the number of trials may be uncertain. Without all conditions satisfied, the binomial framework cannot be applied. A strong grasp of these characteristics ensures accurate interpretation and correct selection of appropriate probability tools throughout AP Statistics.

FAQ

A success must be defined in a way that is unambiguous and applies consistently to every trial. The choice is contextual and should reflect the specific outcome you want to count.

The key requirement is that every trial uses the same definition. If the interpretation of success changes midway, the situation no longer fits a binomial framework.

Yes, provided the estimated probability is treated as constant across all trials.

The binomial model relies on the assumption of a fixed probability, not on knowing the true value with certainty. As long as the chosen estimate is applied consistently and justified by context, the model remains appropriate.

Situations often break independence when one trial influences the next. Examples include:

• Selecting without replacement from a small population.

• Learning or fatigue effects during repeated human tasks.

• Changing conditions such as temperature or pressure affecting results across trials.

When independence is violated, the count of successes cannot be modelled as a binomial random variable.

Often yes, especially when the effect of dependence is negligible in practice.

If the population is large, or the influence between trials is minimal, statisticians commonly treat the trials as independent for modelling purposes.

However, strong or systematic dependence should never be ignored, as it undermines the validity of binomial assumptions.

A fixed number of trials ensures that the random variable counts successes from a predetermined set of opportunities.

If the process continues until a condition is met—such as stopping after the fifth success—the number of trials becomes random, violating a key binomial requirement.

Processes with a variable endpoint generally require different models, such as geometric or negative binomial distributions.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

A factory produces metal clips, and each clip either passes (success) or fails (failure) a quality inspection. The probability a clip passes is constant at 0.92, and the outcome of each inspection is independent of all others. The factory inspects 15 clips.

Explain why the number of clips that pass inspection can be modelled as a binomial random variable.

(3 marks)

Question 1 (3 marks)

• 1 mark: States that each clip has only two possible outcomes: pass or fail.

• 1 mark: States that the probability of success (passing) is constant at 0.92 for all clips.

• 1 mark: States that inspections are independent and there is a fixed number of trials (15 clips).

Full marks awarded for clearly stating all binomial conditions.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

A basketball player takes a series of free throws. On each attempt, the player either scores (success) or misses (failure). The probability of scoring remains constant at 0.75 throughout the training session, and each attempt is independent of the others.

(a) State the conditions required for the number of successful free throws to follow a binomial distribution.

(b) Determine whether this situation meets all binomial conditions and justify your reasoning.

(c) Explain why the number of successful free throws can be considered a binomial random variable.

(6 marks)

Question 2 (6 marks)

(a)

• 1 mark: Mentions two outcomes per trial (success or failure).

• 1 mark: Mentions constant probability of success across trials.

• 1 mark: Mentions independence of trials.

• 1 mark: Mentions fixed number of trials.

(b)

• 1 mark: Correctly states that all binomial conditions are satisfied.

• 1 mark: Provides justification referencing two or more specified conditions (e.g., probability remains 0.75, independence, only two outcomes).

(c)

• 1 mark: Concludes that the number of successful free throws is therefore a binomial random variable because it counts the number of successes in a fixed number of independent trials with constant probability.