AP Syllabus focus:

‘Guidelines for assessing whether the sampling distribution of p-hat is approximately normal by checking that both np-hat and n(1-p-hat) meet or exceed 10, facilitating the assumption of normality for the purpose of constructing confidence intervals.’

Assessing the normality of the sampling distribution of p-hat is essential for constructing valid confidence intervals, ensuring that inference procedures appropriately model the behavior of sample proportions.

Assessing Sample Distribution Normality

A central requirement for using a one-sample z-interval for a population proportion is verifying that the sampling distribution of the sample proportion, denoted p-hat, is approximately normal. This subsubtopic focuses on determining when this normal approximation is justified, based on the size and composition of the sample. Normality is vital because the z-interval relies on the assumption that the sampling distribution behaves like a normal distribution, enabling the use of critical values from the standard normal model.

Why Normality Matters for p-hat

When constructing a confidence interval for a population proportion, students assume that repeated random samples of size n generate sample proportions whose distribution is approximately normal. This shape allows us to model variation using familiar properties of the normal distribution and to compute margins of error with standard methods. However, this approximation is only appropriate when the sample contains sufficient evidence—through counts of both successes and failures—that the normal model behaves reliably.

Understanding p-hat and the Sampling Distribution

The sample proportion p-hat represents the proportion of individuals in the sample who fall into the category of interest. Because p-hat varies from sample to sample due to sampling variability, its distribution must be reasonably well-behaved to support the inference process. When the normality condition fails, the sampling distribution becomes skewed, and confidence interval calculations may be inaccurate.

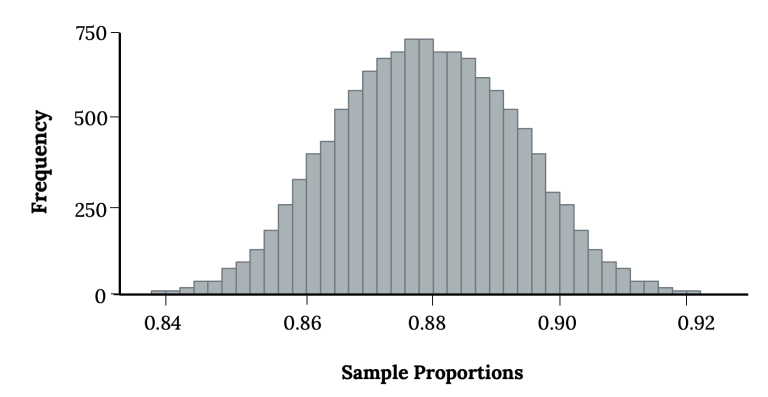

When the normality condition holds, the histogram of p-hat from many random samples is unimodal, symmetric, and well-approximated by a normal curve centered at the true population proportion.

Histogram of a simulated sampling distribution of p-hat from 10,000 samples, showing a symmetric, bell-shaped curve when normality conditions are satisfied. Source.

Sampling Distribution of p-hat: The probability distribution of all possible sample proportions obtained from repeated random samples of the same size taken from a population.

After introducing the sampling distribution, it becomes important to identify when this distribution resembles a normal curve closely enough for z-based methods.

The Normality Condition Using Counts of Successes and Failures

To assess normality, AP Statistics requires checking whether the sample includes enough successes and failures. Specifically, students verify two inequalities based on the observed sample proportion.

EQUATION

= Sample size

= Observed sample proportion

Meeting these conditions indicates that the sampling distribution of p-hat is approximately normal, according to the Central Limit Theorem for proportions, which states that with sufficiently large sample counts, the distribution becomes nearly normal regardless of the population shape.

Interpreting the Counts: Successes and Failures

To apply the condition, the sample must contain both:

At least 10 successes, meaning the number of individuals in the sample possessing the characteristic of interest is sufficiently large.

At least 10 failures, meaning the number of individuals not possessing the characteristic is also sufficiently large.

These thresholds ensure that neither tail of the sampling distribution is excessively thin or distorted.

When the Normality Condition Fails

If either np-hat or n(1 − p-hat) falls below 10:

The sampling distribution becomes skewed, often toward the side of the smaller count.

The margin of error computed using normal methods may be misleading.

The resulting confidence interval may misrepresent the uncertainty in the estimate.

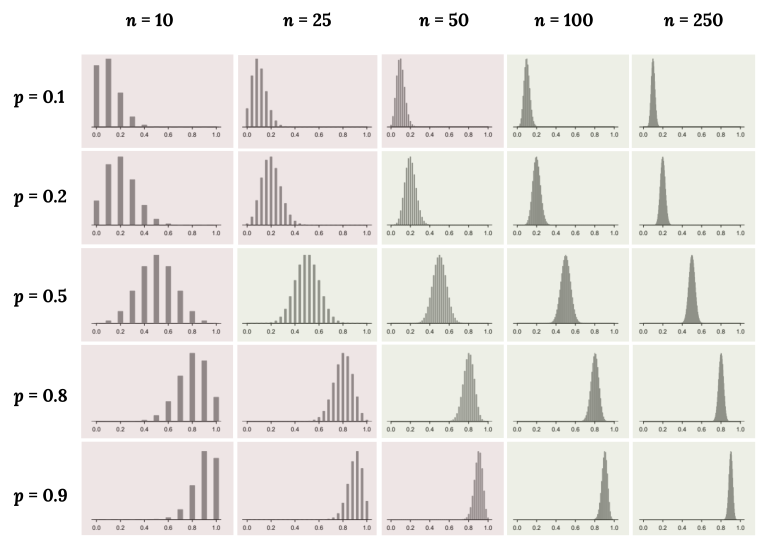

When np-hat or n(1 − p-hat) is small, especially when the true proportion is near 0 or 1, the sampling distribution can be strongly skewed and far from normal.

Grid of sampling distributions illustrating how extreme p values or small sample sizes create skewed, non-normal shapes, while larger expected counts yield distributions that approach normality. Source.

In these situations, alternative methods—such as exact binomial procedures—may be preferred, though such methods are beyond the scope of AP Statistics.

Practical Steps for Students

When assessing sample distribution normality as part of constructing a confidence interval, students typically follow this process:

Identify p-hat.

Use sample data to compute the observed proportion.Compute expected counts.

Multiply the sample size by p-hat and by (1 − p-hat).Check for adequacy.

Confirm that both values meet or exceed the threshold of 10.Validate normality.

Only proceed with the one-sample z-interval if the condition is met.

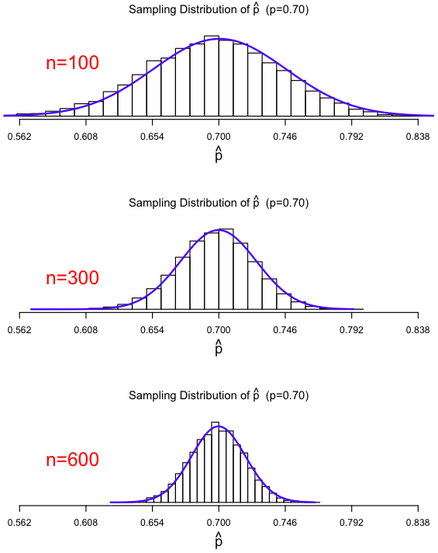

As n increases while p stays the same, the sampling distribution of p-hat becomes more tightly concentrated around p and more closely resembles a normal curve.

Three sampling distributions of p-hat for increasing sample sizes, demonstrating that larger n values produce narrower, more normal-shaped distributions consistent with the success–failure condition. Source.

Connecting Normality to Reliable Inference

Because inference for proportions depends on approximating p-hat’s distribution with a normal curve, this condition directly affects the accuracy of interval estimates. The strength of the normal approximation ensures that the critical value (z)*, standard error, and margin of error accurately quantify uncertainty. When the approximation is valid, students can trust that their confidence interval is properly calibrated and interpretable.

Thus, assessing sample distribution normality is not a procedural formality—it is the foundation for making justified and statistically sound inferences about population proportions using confidence intervals.

FAQ

The closer the true population proportion is to 0.5, the more quickly the sampling distribution becomes approximately normal because both expected successes and failures increase symmetrically.

When the true proportion is very small or very large, much larger sample sizes are needed for the success–failure condition to be met. This is because one of the expected counts grows slowly, making skewness more likely.

Because the true population proportion is unknown, the observed sample proportion is the only available estimate to evaluate expected successes and failures.

This substitution is justified in confidence interval construction, where the objective is to estimate the unknown proportion, and it provides a practical way to assess whether the normal model is appropriate.

The approximation may still be acceptable, but the sampling distribution can show mild skewness.

In borderline cases:

• The tails of the distribution may be slightly heavier or lighter than the normal curve.

• Margin-of-error calculations may be slightly less accurate.

• Intervals remain usable but may not align perfectly with exact binomial methods.

Yes. A large n does not guarantee normality if the observed proportion is extremely close to 0 or 1.

For example:

• Even with a large sample, if p-hat is around 0.01 or 0.99, one of the expected counts (successes or failures) may still be below 10.

This highlights why the rule checks counts rather than sample size alone.

Proportions alone do not indicate how much data supports each category. A small proportion in a small sample may represent only one or two observations, which is insufficient for stable inference.

Using counts ensures that each category has enough observations for the sampling distribution of p-hat to stabilise and resemble a normal curve, allowing z-based confidence intervals to perform reliably.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

A researcher collects a random sample of 200 households and finds that 18% of them own an electric vehicle.

Determine whether it is appropriate to assume that the sampling distribution of the sample proportion is approximately normal. Show your working.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

• 1 mark: Correctly identifies the sample proportion as 0.18.

• 1 mark: Correctly checks expected successes: 200 × 0.18 = 36 (≥ 10).

• 1 mark: Correctly checks expected failures: 200 × 0.82 = 164 (≥ 10) and concludes that the normal approximation is appropriate.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

A public health team conducts a random survey of 120 adults to estimate the proportion who meet daily hydration guidelines. In the sample, 42 adults meet the guidelines.

(a) Assess whether the normality condition for constructing a confidence interval for a population proportion is satisfied.

(b) Explain why checking this condition is important for the validity of the interval.

(c) Suppose the sample size had been reduced to 40 with the same sample proportion. Comment on whether the normality condition would still hold and justify your reasoning.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

(a)

• 1 mark: Correctly calculates the sample proportion as 42/120 = 0.35.

• 1 mark: Correctly checks expected successes: 120 × 0.35 = 42 (≥ 10).

• 1 mark: Correctly checks expected failures: 120 × 0.65 = 78 (≥ 10).

• 1 mark: States that the normality condition is satisfied.

(b)

• 1 mark: Explains that the condition is needed to ensure that the sampling distribution of the sample proportion is approximately normal.

• 1 mark: States that a normal distribution is required to justify the use of z-based confidence intervals.

(c)

• 1 mark: Correctly checks expected successes for n = 40: 40 × 0.35 = 14 (≥ 10).

• 1 mark: Correctly checks expected failures for n = 40: 40 × 0.65 = 26 (≥ 10).

• 1 mark: Concludes that the normality condition would still hold but that the sampling distribution would be more variable due to the smaller sample.