AP Syllabus focus:

‘Type I Error: Occurs when the null hypothesis is true but is incorrectly rejected. Known as a false positive.

- Type II Error: Occurs when the null hypothesis is false but is incorrectly failed to be rejected. Known as a false negative.’

AP Statistics relies on hypothesis testing, and understanding potential errors in this process is essential. These notes explain how Type I and Type II errors arise when making decisions based on sample evidence.

Understanding Errors in Statistical Decisions

When conducting a significance test, statisticians compare sample results to a hypothesized claim about a population. Because tests rely on sample data, the decision may be incorrect even when proper procedures are used. Recognizing the two kinds of incorrect decisions strengthens interpretation of results and clarifies the risks associated with hypothesis testing.

The Role of Hypotheses in Error Types

Significance testing begins with the null hypothesis (H₀), a statement asserting no effect or no difference in the population. The alternative hypothesis (Hₐ) represents the research claim suggesting a real effect or difference. Decisions about these hypotheses can lead to correct conclusions or one of two possible errors.

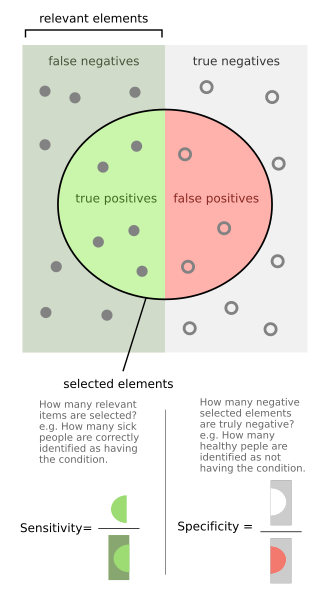

This diagram illustrates true positives, false positives, false negatives, and true negatives, directly connecting false positives to Type I errors and false negatives to Type II errors. Sensitivity and specificity labels extend beyond the AP Statistics syllabus but help contextualize how such errors arise in classification decisions. Source.

Type I Error: Rejecting the null hypothesis when it is actually true; also known as a false positive.

After introducing the Type I error, it is important to emphasize the conceptual meaning. A false positive indicates that sample evidence appears strong enough to contradict H₀ even though the population reality aligns with H₀. This mistake is tied to the fundamental randomness of sampling.

Type II Error: Failing to reject the null hypothesis when it is actually false; also known as a false negative.

A false negative reflects insufficient sample evidence to detect an existing effect or difference. This may occur when the sample size is small, the data are highly variable, or the true parameter differs only slightly from the hypothesized value.

Distinguishing Between Type I and Type II Errors

Recognizing the distinction between error types is crucial because each has different implications depending on the research context.

Interpreting a Type I Error

A Type I error means a test concludes that evidence contradicts the null hypothesis, incorrectly suggesting the presence of an effect. In formal testing procedures, the significance level, denoted α, defines the probability of committing a Type I error. Setting α involves balancing risk and precision; lower α reduces the risk of false positives but may increase the likelihood of false negatives.

Interpreting a Type II Error

A Type II error occurs when the procedure fails to detect a real effect. The probability of a Type II error is typically written as β, and its complement, 1 − β, represents the power of a test—its ability to correctly reject a false null hypothesis. Although α is chosen by the researcher, β depends on multiple factors, including sample size, true effect size, and data variability.

One meaningful sentence is necessary before moving into a mathematical relationship that helps quantify error probabilities.

EQUATION

= Probability of correctly rejecting a false null hypothesis

= Probability of a Type II error

This relationship highlights that reducing β increases a test’s power, improving the likelihood of detecting meaningful effects when they exist.

Factors Affecting the Likelihood of Errors

Statistical decision-making is shaped by conditions that influence the probability of each type of error. Understanding these factors helps researchers design more effective studies.

Factors Increasing Type I Error Risk

Although α constrains the chance of a Type I error, certain choices can unintentionally raise the likelihood of rejecting a true null hypothesis. These include:

Using a very small sample size, leading to unstable estimates

Conducting multiple tests without adjusting α

Relying on poorly controlled experimental conditions

These issues can exaggerate apparent differences in sample data, making false positives more likely.

Factors Increasing Type II Error Risk

Type II errors are more likely when evidence is insufficient to reveal a true effect. Contributing conditions include:

Small sample sizes that produce large standard errors

High variability within the population

A true parameter value that lies close to the null value

A very small significance level, which makes rejecting H₀ more difficult

Each of these conditions reduces the test’s sensitivity, increasing β.

Balancing Type I and Type II Errors

Because decreasing one type of error often increases the other, researchers must consider the context of the study when selecting α and designing data collection.

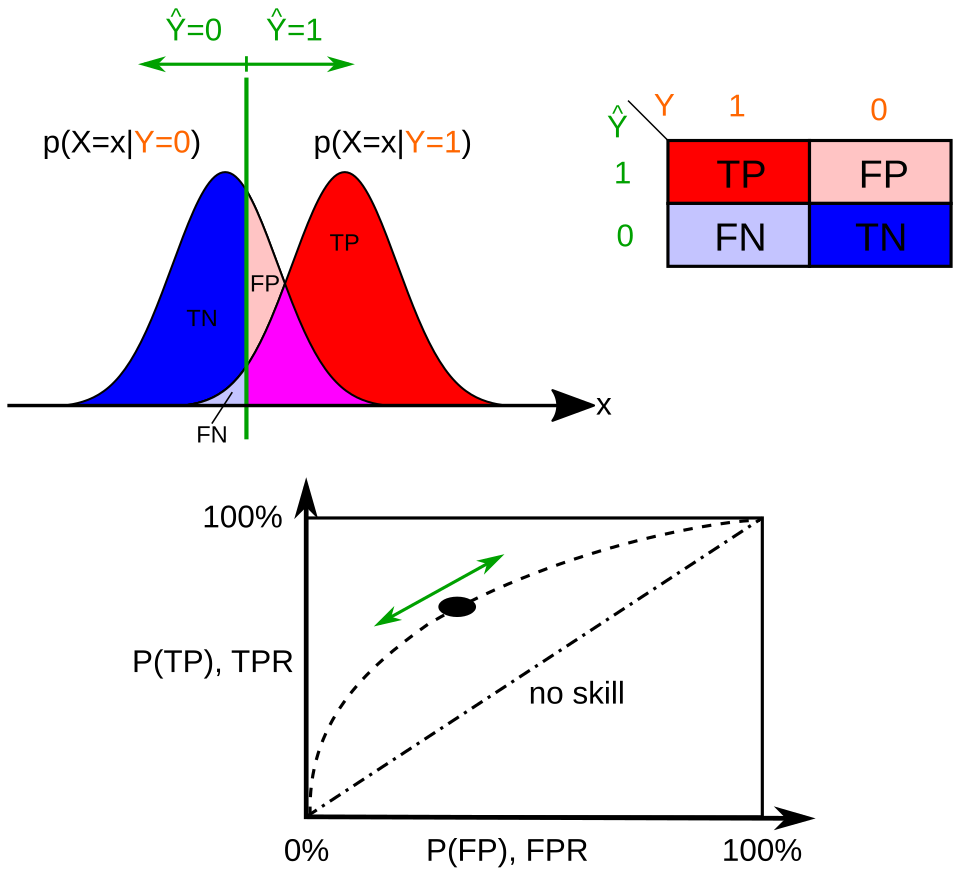

This figure visualizes how shifting a decision threshold changes the balance between false positives (Type I errors) and false negatives (Type II errors). The overlap between distributions illustrates why such errors occur. The ROC curve and extended labeling exceed AP Statistics requirements but effectively demonstrate the fundamental trade-off between the two types of errors. Source.

Using Context to Evaluate Error Impact

Understanding the real-world implications of errors helps guide appropriate statistical decisions. Researchers evaluate:

The cost of a false positive vs. a false negative

Ethical or safety considerations

Practical importance of correctly detecting or ruling out effects

Thoughtfully balancing these factors ensures that hypothesis testing aligns with the goals and responsibilities of the study.

FAQ

A useful way is to link each error type to the phrases false positive (Type I) and false negative (Type II). This anchors the errors to real-world decision outcomes.

Another strategy is to associate Type I errors with being overly cautious about missing an effect, while Type II errors reflect being overly cautious about claiming one exists.

Mnemonic pairs such as “I = Incorrect rejection” and “II = Inadequate evidence to reject” can also help fix the concepts in memory.

A smaller significance level makes the threshold for rejecting the null hypothesis more restrictive, meaning stronger evidence is required.

This increases the probability that a real effect goes undetected because the test is less willing to reject the null hypothesis.

Researchers must balance caution against false positives with the risk of missing meaningful effects.

A Type I error is often more serious in studies where a false claim could lead to harmful or costly actions.

Examples include:

Declaring a medical treatment effective when it is not

Approving an unsafe product

Detecting a nonexistent security threat

In such contexts, wrongly rejecting a true null hypothesis may carry greater consequences than failing to detect a real difference.

Small samples create more variability in estimates, making it harder to detect real differences between the true parameter and the hypothesised value.

Greater sampling variability reduces the test’s power, meaning genuine effects may go unnoticed.

Increasing the sample size stabilises the estimate and improves the ability to identify meaningful deviations from the null.

Researchers consider context, cost, and consequences. The relative seriousness of each error guides the choice.

Common considerations include:

Ethical implications of false positives vs false negatives

Financial or safety risks

Whether missing an effect or falsely claiming one is more damaging

The chosen balance informs the selection of significance level and study design decisions.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

A medical screening test for a certain disease has been shown to incorrectly indicate the presence of the disease in some healthy individuals.

a) Identify which type of error this represents.

b) Briefly explain what this error means in the context of the test.

Question 1

a) 1 mark: Correctly identifies the error as a Type I error.

b) 1–2 marks:

1 mark for stating that the test incorrectly labels a healthy person as having the disease.

1 additional mark for explaining that this means the null hypothesis (that the person is healthy) was wrongly rejected.

Total: 2–3 marks.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

A researcher conducts a significance test for a population proportion with a null hypothesis stating that the proportion of customers satisfied with a service is 0.80. The true proportion is actually 0.72, but the researcher fails to reject the null hypothesis.

a) Identify the type of error that has occurred.

b) Explain why this error occurs in terms of the decision made.

c) Describe one factor that could reduce the likelihood of this type of error if the study were repeated.

d) Explain why reducing the chance of this type of error may increase the likelihood of the other error type.

Question 2

a) 1 mark: Identifies the error as a Type II error.

b) 1–2 marks:

1 mark for stating that the researcher failed to reject the null hypothesis even though it was false.

1 additional mark for explaining that the test missed a real difference between the hypothesised and true proportion.

c) 1 mark: States a valid factor that reduces Type II error probability, such as increasing sample size, increasing significance level, or reducing variability.

d) 1–2 marks:1 mark for noting that decreasing the chance of a Type II error often raises the chance of a Type I error.

1 additional mark for explaining that increasing sensitivity to detect real effects makes the test more likely to reject the null hypothesis, even when it is true.

Total: 4–6 marks.