OCR Specification focus:

‘Accessions, reputations, splendour and ceremony underpinned absolutism; successes and weaknesses varied by reign.’

The Ottoman sultans between 1453 and 1606 exercised immense political, military and religious power. Their authority depended on carefully orchestrated successions, personal charisma, and the display of imperial magnificence that reinforced their image as absolute rulers.

The Nature of Ottoman Accession

Accession to the sultanate was rarely smooth.

Dynastic succession in the Ottoman Empire did not follow strict primogeniture but was often resolved through power struggles between brothers.

The victor emerged through political intrigue, military backing, and at times ruthless measures.

This created both instability and a system that ensured the strongest candidate typically came to power.

Primogeniture: A system of inheritance where the eldest son automatically succeeds his father’s position, usually in monarchy or noble family lines.

The role of the army and court factions was pivotal in shaping which prince ascended. Once secured, the accession was legitimised through ceremonial enthronement, religious endorsement by the ulema (Islamic scholars), and the proclamation of sovereignty across the empire.

The enthronement of Sultan Osman II (1618–22) depicts the formal cülûs ceremony, with officials and religious figures present to bless and proclaim the new ruler. Although slightly later than 1453–1606, it accurately illustrates the Ottoman rites used to legitimise accession. Note the structured choreography and elite presence that communicated splendour, hierarchy, and authority. Source

Character of the Sultans

The personality and leadership style of individual sultans profoundly influenced the stability of the empire.

Mehmed II (r. 1451–1481), known as “the Conqueror,” was defined by his ambition and military genius, exemplified by the capture of Constantinople in 1453.

Gentile Bellini’s 1480 portrait of Mehmed II presents the sultan as a powerful, composed ruler framed by classical motifs, aligning visual prestige with political authority. Such images contributed to Ottoman and European perceptions of the sultan’s reputation. This artwork is directly within the period covered by the syllabus. Source

Suleiman the Magnificent (r. 1520–1566) embodied the pinnacle of imperial prestige, combining military triumphs with codification of law and patronage of culture.

Later sultans such as Selim II (r. 1566–1574) were criticised for indulgence and reliance on advisors, highlighting how weakness at the top could undermine Ottoman power.

The character of the ruler directly shaped the empire’s reputation abroad and the internal cohesion of its political system. Charismatic rulers bolstered the perception of divine favour and invincibility, while weaker sultans left the empire vulnerable to factionalism.

Absolutism and Splendour

The Ottoman sultans were perceived as absolute monarchs, wielding unchallengeable authority over military, religion, and state administration.

Absolutism was expressed through elaborate court rituals, which demonstrated distance between the ruler and subjects.

The sultan’s palace, particularly Topkapi in Istanbul, embodied splendour and magnificence, reinforcing the grandeur of the imperial household.

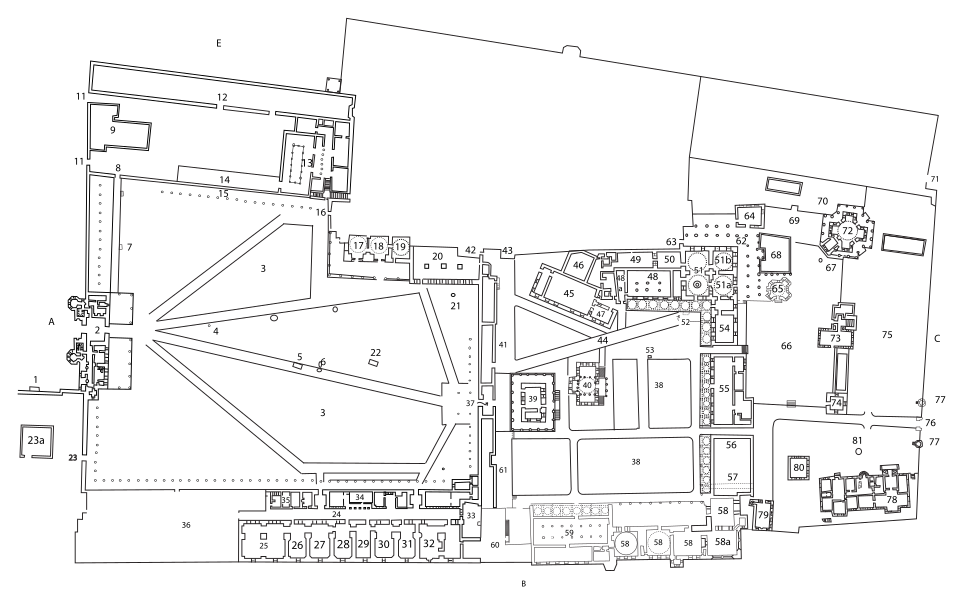

Plan of Topkapı Palace showing the progressively restricted courtyards, the Gate of Felicity, and the Audience Chamber — key settings for ritual, protocol, and controlled access to the sultan. The spatial sequence visualises how architecture buttressed absolutism by regulating proximity to the ruler. The legend includes areas beyond this subsubtopic; focus on the courtyards and audience spaces. Source

Ceremonial events, including processions, audiences with foreign envoys, and religious festivals, were carefully choreographed to project power and divine sanction.

Absolutism: A political system in which the ruler holds total power, unrestricted by laws, institutions, or opposition, often justified by divine right.

Such splendour was not mere extravagance; it was a vital political tool that reinforced the legitimacy of the dynasty and intimidated both domestic elites and foreign rivals.

The Role of Reputation

Reputation was central to sustaining Ottoman authority across diverse territories.

Military victories enhanced the prestige of the sultan and reinforced the empire’s dominance.

Conversely, military failures or signs of weakness could damage imperial reputation and embolden rivals.

The ruler’s personal reputation also influenced the cohesion of provincial administration, the loyalty of the military, and diplomatic relations with European powers.

The dissemination of reputation was achieved through imperial propaganda, monumental architecture, coinage bearing the sultan’s name, and chronicles that glorified achievements.

Ceremony as a Political Tool

Ceremony underpinned absolutism by creating a visible hierarchy centred on the sultan.

Audiences with the sultan required strict protocol, emphasising his elevated status.

The harem and palace rituals symbolised the wealth and exclusivity of the dynasty.

Public ceremonies, such as religious festivals and military parades, reminded subjects of the sultan’s centrality to both faith and empire.

These practices forged a sense of awe and loyalty, integrating political and religious symbolism to affirm the sacred character of the dynasty.

Variation in Success and Weakness

The Ottoman experience from 1453 to 1606 demonstrates how absolutism was both strengthened and weakened depending on the ruler.

Strong sultans like Mehmed II and Suleiman I expanded the empire, consolidated law, and projected unprecedented grandeur.

Weaker successors such as Selim II and Murad III relied heavily on grand viziers, palace favourites, or the harem, diluting the effective exercise of personal rule.

The balance between splendour and effectiveness could determine whether absolutism was reinforced or hollowed out in practice.

Key factors influencing success included:

The ruler’s military ability and charisma.

Stability during accession and avoidance of prolonged succession crises.

Effective use of court ritual and public ceremony to legitimise rule.

Management of reputation through conquest, law, and culture.

The Ottoman Sultan as an Absolute Ruler

By combining accession practices, personal character, and the careful deployment of splendour and ceremony, the Ottoman sultans crafted an image of absolutism. Yet this image depended on performance: strong rulers could transform the empire’s reputation and ensure political cohesion, while weaker rulers risked undermining the very foundations of their authority. The period illustrates the dynamic interplay between image, personality, and ceremony in sustaining the sultan’s role as the centre of the Ottoman world.

FAQ

The Ottomans rejected strict primogeniture to ensure the most capable son could rule. Princes governed provinces during their youth, gaining administrative and military experience. When the reigning sultan died, rival brothers competed for the throne. Victory depended on political alliances, military support, and sometimes brutal elimination of rivals. This system minimised long-term dynastic weakness but created frequent instability at the moment of accession.

The ulema provided religious legitimacy by confirming the new sultan as protector of Islam and upholder of sharia.

They issued blessings or sermons recognising his authority.

Their approval signalled divine sanction, reassuring both elites and common subjects.

By aligning with the ulema, sultans integrated political power with spiritual authority, reinforcing absolutism.

Without this endorsement, a ruler’s claim could be questioned, especially in contested accessions.

Public processions were highly orchestrated events showcasing wealth and order.

The sultan appeared surrounded by guards, banners, and music, projecting invincibility.

Subjects witnessed the grandeur of their ruler firsthand, reinforcing loyalty.

Foreign envoys also observed, reporting back on the empire’s strength.

These processions reminded populations of the sultan’s centrality to both the political system and the faith, blending spectacle with political messaging.

The palace’s layout reflected hierarchy and control.

Courtyards narrowed access, symbolising increasing exclusivity and authority.

The Gate of Felicity marked the transition to sacred royal space, accessible only to select officials.

The Audience Chamber controlled interactions with foreign envoys, emphasising distance and power.

This architectural symbolism made the sultan physically and politically remote, reinforcing his absolute authority.

European diplomats, merchants, and travellers reported on the sultans they encountered. Their writings often shaped international reputations, highlighting either magnificence or decadence.

Strong rulers like Mehmed II or Suleiman were described as disciplined and formidable.

Later sultans were sometimes criticised as weak or indulgent, reflecting political realities.

These external perspectives circulated widely, influencing diplomacy and how European powers judged the Ottoman threat.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks)

Give two ways in which the accession of an Ottoman sultan was legitimised.

Mark Scheme:

1 mark for each valid way identified.

Acceptable answers include:

• Through ceremonial enthronement (cülûs) (1 mark)

• By endorsement of the ulema or religious blessing (1 mark)

• By proclamation of sovereignty across the empire (1 mark)

Maximum 2 marks.

Question 2 (6 marks)

Explain how splendour and ceremony reinforced the absolutism of the Ottoman sultans between 1453 and 1606.

Mark Scheme:

Level 1 (1–2 marks): Generalised or descriptive answers with limited reference to splendour or ceremony, e.g. “The Ottomans had a palace” or “They used rituals.”

Level 2 (3–4 marks): Clear explanation of at least one way splendour and ceremony supported absolutism. May include reference to Topkapı Palace or court rituals. Some link to absolutism but limited development.

Level 3 (5–6 marks): Developed explanation with two or more ways splendour and ceremony reinforced absolutism. Stronger answers will explicitly connect ritual and magnificence (e.g. court audiences, festivals, Topkapı’s restricted access) to the projection of authority and unchallengeable power.

Maximum 6 marks.