OCR Specification focus:

‘The extent of power and centralised authority depended on cooperation and control over nobility.’

Introduction

The relationship between monarchy and nobility defined the strength of central government in France from 1498 to 1610, shaping centralisation, authority, and the development of monarchy.

The Role of the Nobility in Central Power

The nobility represented both a vital support system and a major obstacle to centralisation. Monarchs relied on noble cooperation for military campaigns, local administration, and maintaining order, yet excessive autonomy threatened royal authority. The French crown had to balance rewards and repression to ensure loyalty, while promoting the monarchy’s image as the natural centre of power.

The Importance of Noble Privileges

French nobles enjoyed extensive privileges, including exemption from many taxes and rights over tenants. Such privileges provided them with both prestige and financial security. However, this meant that while the monarchy depended on nobles for governance, it faced difficulties in enforcing equality and central control. Monarchs often struggled against entrenched regionalism and noble independence.

Privilege: A set of rights, exemptions, and honours conferred upon individuals or groups, often hereditary, which distinguished the nobility from common subjects.

The persistence of noble privilege forced monarchs to pursue gradual centralisation rather than direct confrontation, using methods of patronage and negotiation.

Methods of Centralisation

Centralisation was a process of strengthening authority at the expense of competing powers. The monarchy employed multiple strategies:

Patronage: Distributing offices, pensions, and honours to bind nobles to the crown.

Venality of Office: Allowing nobles to purchase offices in government and judiciary, creating dependence on royal favour.

Military Control: Establishing command over noble-led armies and reducing reliance on private noble forces.

Legal Institutions: Using the Parlements and royal courts to extend the king’s legal authority across regions.

Jurisdictions of the Parlements and related sovereign/provincial councils across France. The map illustrates the crown’s regional legal reach that underpinned centralisation against noble independence. Extra detail: boundaries shown are for the broader Ancien Régime and not fixed precisely to 1498–1610. Source

Royal Officials (Intendants in later developments): Early forms of centrally appointed officials monitored noble activity and ensured local enforcement of royal policy.

These strategies limited noble independence, though full absolutism had yet to emerge.

Noble Resistance and Conflict

Nobles did not always accept centralisation. Periodic rebellions demonstrated resistance to perceived threats to autonomy. The most famous early example was the Constable Bourbon’s revolt (1523), which exposed the limitations of royal authority when powerful nobles defected.

Engraved portrait of Charles III, Duke of Bourbon, Constable of France. His 1523 defection exemplifies how overmighty nobles could destabilise central authority. High-resolution engraving by Thomas de Leu. Source

Although suppressed, it highlighted the monarchy’s vulnerability to noble disunity.

Factionalism also weakened central authority.

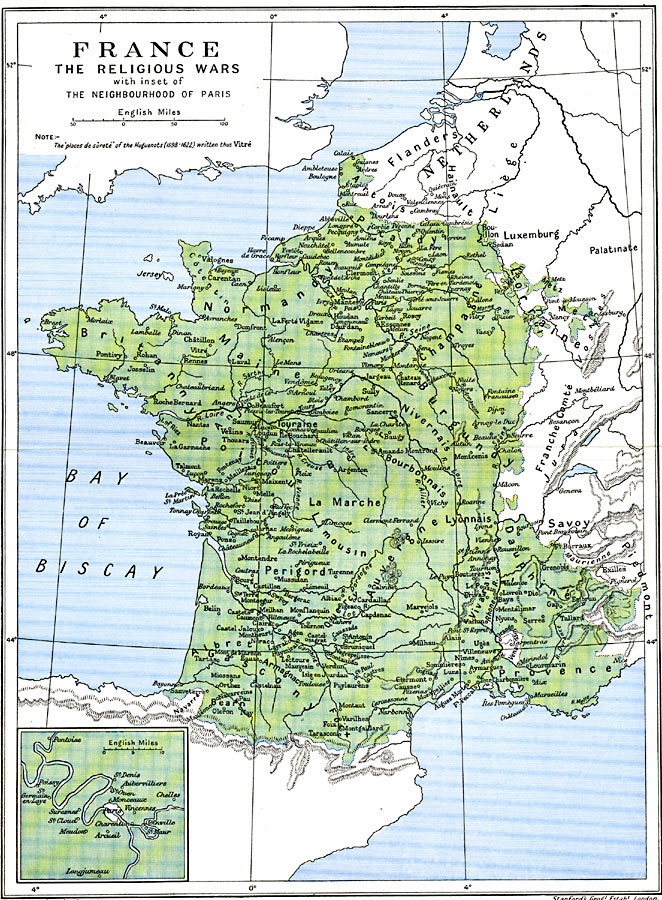

Map of France during the Wars of Religion showing contested regions and Huguenot places de sûreté. It situates noble–confessional power bases that constrained royal centralisation before 1598. Extra detail: the key includes fortified places maintained to 1622, just beyond the syllabus window. Source

Rivalries between noble families, especially during the Wars of Religion (1562–1598), fractured national unity and forced monarchs to negotiate rather than dictate. Control over the nobility was thus inseparable from managing broader religious and political conflict.

The Guise and Bourbon Rivalries

The Guise family, staunchly Catholic, and the Bourbon dynasty, associated with Protestantism, exemplified noble power challenging the monarchy. Their rivalry often overshadowed the crown, limiting centralisation and undermining authority. The monarchy’s ability to mediate and eventually suppress such rivalries determined its success in restoring central control.

Royal Authority under Successive Monarchs

Francis I (1515–1547)

Francis I extended central authority through patronage and a court culture centred at Fontainebleau. However, dependence on noble cooperation limited the push toward absolutism. He consolidated power by making nobles part of royal administration, though this increased reliance on venal offices.

Henry II (1547–1559)

Henry II strengthened legal centralisation and used royal justice to limit noble jurisdiction. Yet, costly wars weakened finances, forcing him to make concessions to nobles to secure loyalty.

Charles IX and Henry III (1560–1589)

During the Wars of Religion, noble power surged as regional leaders armed their followers. The monarchy’s reliance on noble militias eroded central authority, with noble factions dominating politics. The crown’s authority was constantly under siege by competing noble ambitions.

Henry IV (1589–1610)

Henry IV restored royal authority after the wars by reconciling factions, rewarding nobles with positions, and re-establishing central control. His use of Sully’s reforms reinforced financial stability, reducing dependence on noble subsidies. While he relied on noble support for recovery, he successfully curbed the power of overmighty subjects and strengthened central authority.

Cooperation versus Control

The balance between noble cooperation and control defined the extent of royal centralisation. Monarchs could not rule without noble support, yet excessive noble independence undermined stability. The crown therefore pursued policies that:

Integrated nobles into the administrative hierarchy.

Offered rewards in exchange for loyalty.

Limited independent noble military power.

Promoted the monarchy as the supreme symbol of unity.

Centralisation: The process of consolidating authority in the monarchy, reducing the power of regional or noble institutions to achieve unified governance.

This process laid the foundations of absolutism, though by 1610 France was not yet a fully absolutist state. The monarchy’s authority was still dependent on managing noble cooperation.

Impact on Nation-State Development

The struggle between monarchy and nobility had profound effects on the emergence of the French nation state:

Successful centralisation fostered unity and the perception of the king as the sole source of authority.

Noble resistance highlighted the fragility of royal power and the difficulty of enforcing uniform rule across provinces.

The Wars of Religion demonstrated how noble autonomy could destabilise the kingdom.

Henry IV’s reign marked a turning point, as effective cooperation restored stability and central authority, strengthening the monarchy’s claim to lead a unified nation.

FAQ

French monarchs frequently relied on noble loans or subsidies to fund wars and court expenses. This created a dynamic where nobles could influence policy by withholding support.

Instead of direct confrontation, kings often extended privileges or offices as compensation, limiting their ability to enforce uniform financial authority.

Nobles used fortified châteaux as symbols of independence and bases of local authority.

These structures provided refuge in times of conflict.

They also acted as administrative centres where nobles maintained client networks.

Their existence meant monarchs could not easily project power without noble cooperation.

Patronage tied nobles’ fortunes directly to the monarchy. Offices, pensions, and honours created personal loyalty that discouraged rebellion.

However, this system also reinforced dependence on royal favour. Ambitious nobles could still feel excluded if patronage was uneven, leading to factional rivalries that threatened unity.

Religious allegiance amplified political rivalries. Catholic noble families such as the Guise gained legitimacy as defenders of faith, while Protestant Bourbons positioned themselves as champions of reform.

This religious dimension legitimised noble opposition to the crown, as they claimed moral authority in addition to traditional privilege.

Monarchs promoted alternative loyalties by appointing royal officials, particularly in sensitive regions.

These officials bypassed noble intermediaries in legal and financial matters.

Royal propaganda emphasised the king’s role as the supreme protector of justice.

Such tactics weakened local noble networks but required careful balance to avoid alienating powerful families.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks)

Identify two methods used by French monarchs between 1498 and 1610 to centralise authority over the nobility.

Mark Scheme:

1 mark for each valid method identified, up to a maximum of 2 marks.

Acceptable answers include: patronage, venality of office, military control, use of Parlements/legal institutions, appointment of royal officials.

Question 2 (6 marks)

Explain how the nobility limited the ability of French monarchs to centralise authority between 1498 and 1610.

Mark Scheme:

Level 1 (1–2 marks): Simple statements with limited explanation (e.g. “The nobles had privileges” or “They rebelled”).

Level 2 (3–4 marks): Clear explanation of one way the nobility limited centralisation, with some detail (e.g. privileges exempted nobles from taxation, limiting financial control).

Level 3 (5–6 marks): Detailed explanation of at least two ways the nobility limited centralisation, with specific examples (e.g. Constable Bourbon’s revolt of 1523 undermined authority; noble factionalism during the Wars of Religion forced monarchs to negotiate rather than impose control). Marks awarded for depth, clarity, and accurate contextual knowledge.