AP Syllabus focus:

‘Solve applied rate-of-change problems involving geometric formulas or physical quantities, using derivatives to connect how one measurement changes when another related measurement changes.’

Geometric and physical rate problems use relationships between measurable quantities to determine how quickly one quantity changes as another varies. These problems rely on interpreting derivatives within structured, real-world relationships.

Understanding Geometric and Physical Rate Problems

Geometric and physical rate problems arise when two or more related measurements change over time, and the rate of one quantity must be found from the rate of another. These situations typically involve formulas from geometry or physics that connect the variables through an equation. By differentiating that equation with respect to time, you obtain a relationship between their respective rates of change.

The Role of Differentiation in Applied Rates

These problems use derivatives as rates of change, meaning each derivative represents how quickly a quantity is varying at a specific instant. Because geometric or physical formulas often involve products, powers, or composite functions, implicit differentiation becomes essential.

Implicit Differentiation: Differentiating an equation involving multiple variables by treating each variable as a function of time and applying the chain rule to every term.

In geometric and physical contexts, the chain rule ensures that derivatives accurately reflect how all quantities evolve with respect to time.

Identifying Variables and Relationships

Before differentiating, the first task is to identify the primary quantities, their units, and how they relate geometrically or physically. Geometric relationships often come from formulas for area, volume, surface area, or perimeter, while physical relationships may involve force, pressure, or density.

Common Geometric Relationships

Many geometric rate problems rely on classical formulas. When such formulas must be differentiated, it is essential to treat every geometric quantity as time-dependent.

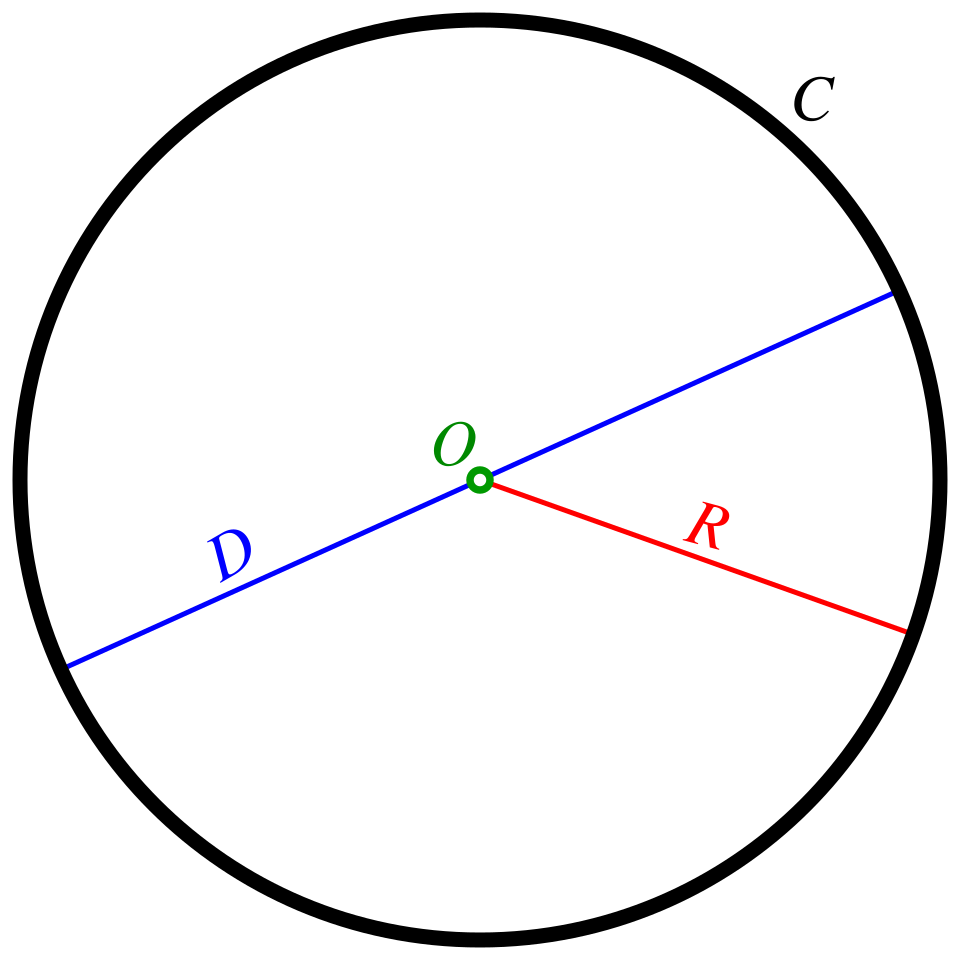

This diagram shows a circle with its center O, radius R, diameter D, and circumference C labeled. It helps connect formulas such as to the geometric features they represent. The inclusion of center and circumference labels adds minor extra detail beyond the AP Calculus AB focus but remains supportive for understanding. Source.

= area (square units)

= radius (linear units)

A normal interpretation sentence appears here to guide the student in applying equations only when appropriate to a situation.

= volume (cubic units)

= radius (linear units)

Recognizing which geometric formula governs a situation allows you to build the equation connecting the changing quantities.

Common Physical Relationships

Physical rate problems may involve relationships in which one measurable quantity influences another according to a physical law.

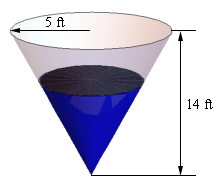

This figure shows an inverted conical tank with water depth h and surface radius r labeled, illustrating how physical quantities like volume depend on changing geometric measurements. It reflects structures common in geometric and physical rate problems. Numerical labels such as 5 and 14 come from a specific example and extend slightly beyond the general AP syllabus requirements. Source.

Differentiating Geometric and Physical Equations

Once the relevant equation is identified, the next step is to differentiate with respect to time. Because geometric and physical formulas typically include variables raised to powers or multiplied together, differentiation must be handled carefully.

Using the Chain Rule With Measurements

Whenever a variable represents a changing measurement, its derivative must include . Differentiating an equation such as requires applying the chain rule, ensuring that both the function and the variable’s rate appear in the derivative expression.

Product and Power Considerations

Many physical relationships involve products (such as force multiplied by displacement) or powers of variables (such as radius cubed). While the product rule may appear in some contexts, geometric and physical rate problems in AP Calculus AB frequently emphasize the power rule combined with the chain rule.

Rate of Change: The derivative of a quantity with respect to time, interpreted as its instantaneous change per unit time.

These derivative expressions allow students to isolate and solve for the required unknown rate.

Interpreting Units and Physical Meaning

Interpreting the units of rates is crucial because geometric and physical problems often combine different measurement types. Students must ensure that units are consistent and meaningful within the problem’s context.

Compound Units in Applied Rates

Rates often include compound units, such as square units per second or cubic units per minute. These express how quickly area or volume is expanding or contracting. Accurate unit tracking helps verify whether an answer makes physical sense.

Direction and Sign of Rates

A positive rate typically indicates an increasing measurement, while a negative rate signifies a decreasing measurement. Interpreting the sign within the context of the situation is an essential skill.

Strategic Process for Geometric and Physical Rate Problems

To approach these applied problems effectively, students should follow a structured process:

Identify all variables that change with time.

Determine the governing equation connecting the geometric or physical quantities.

Differentiate implicitly with respect to time, applying the chain rule to every variable.

Substitute known values at the relevant instant.

Solve for the desired rate, ensuring the units and sign are appropriate.

Connecting Measurement Changes Through Derivatives

Ultimately, geometric and physical rate problems emphasize how derivatives link one changing measurement to another. Because these relationships arise naturally from geometric structure or physical law, calculus provides a powerful framework for determining instantaneous rates in a wide range of applied situations.

FAQ

Choose the formula that directly links the measurements that are changing in the problem. If several formulas seem possible, pick the one that allows substitution of known relationships without introducing unnecessary variables.

Focus on formulas that contain the quantity whose rate is required. If multiple quantities are changing, ensure the formula connects them in a single equation before differentiating.

Many shapes have multiple dimensions that depend on each other. If you differentiate without first reducing the number of variables, you may end up with a derivative containing unknown rates you cannot evaluate.

Expressing variables in terms of one central measurement (for instance, height in a cone) ensures the final derivative contains only quantities relevant to the specific instant described.

A frequent error is forgetting that every geometric measurement varies with time, leading students to differentiate a variable as if it were constant.

To avoid this:

• Treat all dimensions as functions of time.

• Apply the chain rule even when it seems unnecessary.

• Check each term to ensure its derivative includes the correct rate notation.

Signs indicate whether a measurement is increasing or decreasing. In geometric settings, a positive value typically signals expansion, while a negative value suggests contraction.

In physical settings, the sign can show whether a system is filling, emptying, stretching, or compressing. Interpreting sign correctly prevents contradictions with the physical situation described.

These shapes have simple, well-known formulas that produce meaningful rate relationships when differentiated. Their dimensions scale predictably, allowing students to see how one measurement influences another.

They also model common physical situations, such as inflating balloons, water tanks, or spreading material, making them ideal for testing understanding of real-world rate interactions.

Practice Questions

(1–3 marks)

A circular oil spill on the surface of the sea expands so that its radius is increasing at a constant rate of 0.4 metres per minute. At the instant when the radius is 5 metres, find the rate at which the area of the oil spill is increasing.

(1–3 marks)

• 1 mark for using the relationship A = pi r^2.

• 1 mark for differentiating to obtain dA/dt = 2 pi r (dr/dt).

• 1 mark for substitution of r = 5 and dr/dt = 0.4 to obtain a correct numerical rate.

(4–6 marks)

Water is being poured into a conical container with a fixed height of 12 centimetres and a fixed radius of 6 centimetres. At a particular instant, the depth of the water is 4 centimetres and is increasing at 0.5 centimetres per second.

(a) Express the radius of the water’s surface in terms of the depth of the water.

(b) Find the rate at which the volume of water in the container is increasing at that instant.

(c) Interpret your answer to part (b) in the context of the situation.

(4–6 marks)

(a)

• 1 mark for recognising similarity of triangles and obtaining r/h = 6/12.

• 1 mark for correctly stating r = h/2.

(b)

• 1 mark for using V = (1/3) pi r^2 h.

• 1 mark for substituting r = h/2 into the volume formula.

• 1 mark for differentiating with respect to time and substituting h = 4 and dh/dt = 0.5 to obtain a correct numerical rate.

(c)

• 1 mark for a clear contextual interpretation that the volume of water in the container is increasing at the calculated rate at that instant.