Spatial concepts form the foundation of geographic thinking. They help geographers analyze how things are distributed across space, how places interact, and how human and physical systems are organized geographically. By applying spatial concepts, we can examine patterns, relationships, and processes that shape the world.

Absolute and Relative Location

Understanding location is a key spatial concept that enables geographers to describe where things are on Earth. There are two main ways to describe location: absolute location and relative location.

Absolute Location

Absolute location is the fixed, specific position of a place on the Earth’s surface, usually expressed in terms of latitude and longitude. This global coordinate system allows us to pinpoint any location with mathematical precision.

For example:

The Statue of Liberty is located at 40.6892° N, 74.0445° W.

The Great Wall of China can be identified near 40.4319° N, 116.5704° E.

The South Pole is located at 90° S, 0° E.

These coordinates do not change, regardless of time, context, or human interpretation. Absolute location is used in GPS navigation, mapmaking, scientific research, and geospatial technologies to provide exact points on Earth’s surface.

Relative Location

Relative location refers to a place’s position in relation to other places or landmarks. It is context-dependent and changes based on perspective or purpose.

Examples include:

“The airport is five miles south of downtown.”

“Chicago is located on the southwestern shore of Lake Michigan.”

“Egypt is north of Sudan and west of the Red Sea.”

Unlike absolute location, relative location can shift depending on transportation access, infrastructure development, or political context. It plays a key role in understanding trade routes, cultural diffusion, migration flows, and geopolitical relations.

Relative location is especially useful for describing places to others in everyday conversation, navigation without GPS, and analyzing how proximity affects interaction.

Place

While location answers “where,” the concept of place answers “what is it like?” Place is defined by a unique combination of physical and human characteristics that give meaning and identity to a location.

Characteristics of Place

Each place has a distinctive character shaped by:

Physical attributes such as climate, terrain, elevation, vegetation, and natural resources.

Human attributes such as architecture, languages, religion, politics, economy, and culture.

For instance:

Venice, Italy is recognized for its canals, Renaissance architecture, and tourism.

Dubai, UAE is known for its skyscrapers, luxury lifestyle, and desert climate.

Yellowstone National Park is notable for geysers, wildlife, and geothermal features.

Place is not merely a spot on a map. It reflects the identity and experience of those who live there or visit. Geographers study place to understand cultural landscapes, regional identities, and the relationship between people and their environments.

Spatial Interaction

Spatial interaction describes the flow of people, goods, ideas, and information between different places. It focuses on movement and connections across geographic space and helps explain how distant places are linked economically, socially, and culturally.

The three key factors that determine the degree of spatial interaction are:

Complementarity – The degree to which one place has something another place wants or needs.

Transferability – The ease with which goods or ideas can be moved from one place to another, considering cost and technology.

Intervening Opportunities – Alternative places that offer the same product or service, potentially reducing interaction with the original destination.

Time and Distance Decay

Time-distance decay is a concept that suggests the farther away and longer it takes to get somewhere, the less likely interaction will occur. This principle is observable in daily life.

Examples:

You’re more likely to shop at a nearby grocery store than one across town.

Cultural influence weakens the farther it spreads from its origin.

Tourists tend to travel to destinations that are more accessible.

Technology has significantly reduced the effects of time-distance decay:

The internet allows instant communication worldwide.

High-speed transportation shortens travel time.

Social media spreads trends globally in seconds.

Despite these advances, distance still matters in economic decisions, migration patterns, and urban development.

Diffusion

Diffusion is the process through which a cultural element, innovation, or idea spreads from its origin to other locations. Studying diffusion helps geographers trace the movement of religion, language, disease, technology, fashion, and political ideologies.

Types of Diffusion

There are two primary categories of diffusion: relocation diffusion and expansion diffusion.

Relocation Diffusion

Relocation diffusion occurs when people physically move and bring cultural elements with them. The characteristic doesn’t spread from one person to another in place but is carried to a new location entirely.

Examples:

The spread of Islam to Southeast Asia by Arab traders.

The introduction of Spanish in Latin America during colonization.

Pizza and pasta culture brought to the U.S. by Italian immigrants.

This type of diffusion often involves migration, colonization, or diaspora communities and is critical for understanding how cultures mix and evolve.

Expansion Diffusion

Expansion diffusion occurs when a cultural trait spreads outward from its hearth, while remaining strong at the origin. Several subtypes help describe how this occurs:

Patterns of Diffusion

Hierarchical Diffusion

This type of diffusion spreads from authorities, influential figures, or major nodes to other segments of society.

Examples:

Fashion trends from celebrities influencing youth culture.

Government policies adopted first in capital cities before reaching rural areas.

Popular music originating in urban centers then reaching smaller towns.

Hierarchical diffusion reflects the impact of power, influence, and communication structures.

Contagious Diffusion

Contagious diffusion spreads rapidly and broadly through contact between individuals, similar to the transmission of a virus.

Examples:

A viral TikTok trend reaching millions in days.

The spread of slang, memes, or jokes across social media.

The transmission of diseases like influenza or COVID-19.

It’s typically fast, widespread, and doesn't follow a hierarchy—everyone is equally likely to adopt the trait.

Stimulus Diffusion

Stimulus diffusion happens when the core idea spreads, but the specific trait is altered to better suit the receiving culture.

Examples:

McDonald’s in India doesn’t serve beef but offers vegetarian items inspired by local cuisine.

Apple’s design principles influencing other tech brands, but with different operating systems.

Chinese fast food chains adapting American-style menus to reflect local tastes.

Stimulus diffusion shows how global ideas are shaped by local culture, creating hybrids.

Spatial Patterns

Spatial patterns refer to the geographic arrangement of phenomena across Earth’s surface. Recognizing these patterns helps geographers explain processes like urban growth, disease spread, or cultural diffusion.

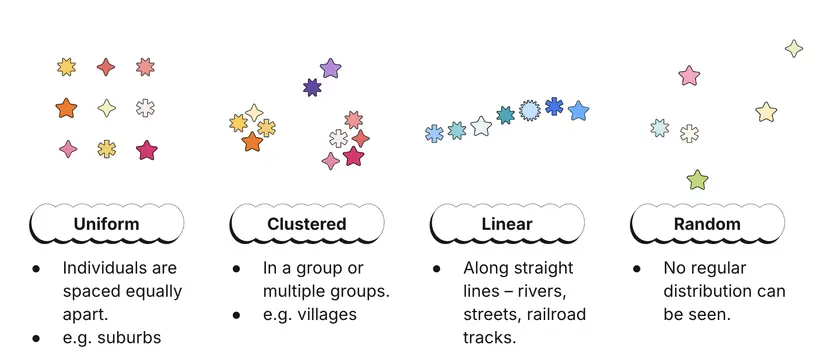

Common Types of Spatial Patterns

Clustered (Agglomerated): Items are close together in space, such as houses in a dense neighborhood or businesses in a shopping mall.

Dispersed (Scattered): Items are spread out, like farms in a rural area.

Linear: Features are arranged in a line, such as towns along a river or railway.

Radial: Patterns spread outward from a central point, such as public transit routes from a city center.

Random: No apparent pattern, like the distribution of restaurants in some urban areas.

Understanding spatial patterns helps identify trends, forecast changes, and manage development.

Connectivity and Accessibility

Connectivity and accessibility determine how linked places are and how easily they interact. These concepts directly impact spatial interaction, economic activity, and social dynamics.

Connectivity

Connectivity refers to the directness and number of connections between locations. More connectivity means easier flow of goods, information, and people.

Examples:

A city with highways, rail lines, and air routes has high connectivity.

Digital connectivity includes broadband access and mobile networks.

Accessibility

Accessibility measures the ease of reaching a destination. It depends on transportation, infrastructure, and physical geography.

Examples:

A mountain village with no roads has low accessibility.

Airports with global flights increase accessibility for their cities.

Both connectivity and accessibility influence trade, migration, urban growth, and service delivery.

Spatial Association

Spatial association exists when two or more phenomena occur in the same location and show potential relationships.

Examples:

Low income areas and higher rates of asthma, possibly due to industrial pollution.

Agricultural regions with high pesticide use and nearby water contamination.

Urban areas with higher population density and increased COVID-19 transmission.

It’s important to remember that spatial association does not prove causation, but it can point to meaningful connections that warrant deeper investigation.

Sense of Place

Sense of place refers to the emotional and cultural meanings attached to a location. It reflects personal experiences, memories, traditions, and social connections.

Examples:

A childhood home holding sentimental value.

Jerusalem’s religious significance for multiple faiths.

Times Square symbolizing urban energy and entertainment.

A strong sense of place contributes to community identity, pride, and attachment. It also influences how people respond to urban development, natural disasters, or social change.

Friction of Distance

Friction of distance describes the resistance or effort required to move across space. As distance increases, interaction tends to decrease unless technology or infrastructure compensates.

Implications:

High friction areas are remote and underdeveloped.

Low friction areas have robust networks and strong global ties.

Reduced friction leads to increased globalization and faster diffusion.

The concept helps explain uneven development, accessibility gaps, and travel behavior.

Tobler’s First Law of Geography

Tobler’s First Law of Geography states:

“Everything is related to everything else, but near things are more related than distant things.”

This law emphasizes that spatial proximity matters in shaping relationships and patterns. It underlies most spatial analysis in geography, from urban planning to epidemiology. Whether studying markets, ecosystems, or cultural diffusion, the principle reinforces the role of distance in geographic relationships.

FAQ

Spatial concepts provide the framework for analyzing how cities grow, change, and interact with surrounding areas. Geographers use tools like spatial patterns, diffusion, and interaction to interpret how land is used, where populations concentrate, and how infrastructure develops.

Patterns help identify where residential, commercial, and industrial zones form (e.g., concentric or sector models).

Spatial interaction explains commuting flows and the connectivity of suburbs and city centers.

Time-distance decay shows why downtowns have stronger influence than distant exurbs.

Hierarchical diffusion accounts for how planning trends or technologies spread between cities.

These concepts help predict future growth and guide urban planning.

Friction of distance refers to the effort, time, and cost required to move people or goods across space. In economic geography, it plays a critical role in shaping trade relationships, business locations, and supply chains.

Areas with high friction (remote or poorly connected) face limited trade opportunities and higher costs.

Low friction zones, like major port cities, attract investment and function as trade hubs.

Modern infrastructure and technology (airports, internet) reduce friction, allowing companies to operate globally.

Friction explains why businesses cluster in well-connected regions and why some rural areas struggle economically.

It remains a key variable in location decisions and development planning.

Spatial diffusion is central to how religions and languages spread over time and space. Through relocation and expansion diffusion, these cultural elements move beyond their points of origin and become embedded in new regions.

Relocation diffusion occurs when missionaries, colonizers, or migrants bring their faith and language to new lands.

Hierarchical diffusion explains how rulers or elites adopt a religion, which then spreads to the general population (e.g., Christianity in the Roman Empire).

Contagious diffusion applies when everyday contact between people spreads religious practices or languages across adjacent areas.

Over centuries, these diffusion processes result in linguistic and religious diversity shaped by movement and interaction.

Spatial association identifies patterns where different phenomena occur in the same locations, helping policymakers make data-driven decisions. Recognizing these spatial relationships allows for targeted responses to specific geographic issues.

Planners use spatial association to detect links between poverty and limited healthcare access.

Mapping crime rates alongside lighting or infrastructure reveals safety challenges.

Overlapping data on pollution and respiratory illness guides environmental regulations.

Spatial association helps distribute resources more equitably by highlighting underserved regions.

By analyzing these patterns, governments can craft more effective and equitable policies grounded in geographic realities.

Spatial concepts shape how human activity interacts with the environment, influencing the appearance and meaning of cultural landscapes. A cultural landscape reflects both the physical features and the human imprint on a place.

Place and sense of place determine how people identify with and modify spaces.

Diffusion brings architectural styles, agricultural practices, or technologies to new regions, changing the visual environment.

Relative location affects cultural exposure and external influences, especially near borders or trade routes.

Spatial patterns like clustering or dispersion affect settlement types (e.g., compact villages vs. dispersed farms).

These concepts help geographers decode how identity, tradition, and innovation are reflected in built environments.

Practice Questions

Compare and contrast hierarchical diffusion and contagious diffusion, providing a geographic example of each.

Hierarchical diffusion spreads from authoritative or influential nodes to other locations, often following a structured pattern. For example, fashion trends may originate in major cities like Paris and gradually influence smaller towns. In contrast, contagious diffusion spreads rapidly and widely through direct contact, regardless of hierarchy. An example is the spread of the “Ice Bucket Challenge,” which quickly went viral through social media across all age and social groups. While hierarchical diffusion depends on influence and status, contagious diffusion relies on widespread personal interaction. Both are types of expansion diffusion but differ in their pathways and rate of spread.

Explain how relative location can change over time and discuss one consequence of that change for a specific place.

Relative location is context-dependent and can shift with changes in transportation, technology, or economic development. For example, the relative location of Dubai changed dramatically with the development of international air travel. Once considered a remote desert city, Dubai became a global hub situated “between Europe and Asia,” with enhanced accessibility and connectivity. This shift attracted international investment, tourism, and business, transforming its economy and urban landscape. The change in relative location contributed to rapid urbanization and made Dubai a key node in global networks. This demonstrates how human decisions and technological advancements reshape geographic perceptions and significance.