AP Syllabus focus:

‘Assimilation is a diffusion effect in which a group becomes absorbed into the dominant culture, reducing cultural differences.’

Assimilation plays a major role in reshaping cultural identities and landscapes when groups interact over long periods of time. These notes explore how assimilation operates, why it varies by context, and how it transforms cultural visibility and practice.

Understanding Assimilation

Assimilation is a cultural diffusion effect that occurs when sustained contact between groups results in one cultural group—typically a minority—adopting the dominant culture’s traits to such an extent that distinct cultural markers diminish.

Defining Assimilation

Assimilation: The process through which a minority cultural group adopts the traits, norms, and behaviors of a dominant group to the extent that cultural distinctions fade.

Assimilation differs from acculturation, which involves adopting traits while maintaining a separate cultural identity. In contrast, assimilation typically results in the weakening or loss of the original cultural identity over time.

Degrees and Types of Assimilation

Assimilation does not occur uniformly; it varies in intensity and across cultural domains. Geographers examine several dimensions:

Cultural assimilation: Changes in language, religion, foodways, and social norms.

Structural assimilation: Entry into the dominant society’s institutions, including work, housing, education, and political structures.

Spatial assimilation: Residential integration as minority groups disperse into areas once dominated by the majority population.

Identificational assimilation: Shifts in self-perception, loyalty, or group identity toward the dominant culture.

These dimensions help geographers understand the layered nature of assimilation and how it unfolds across generations.

Forces Driving Assimilation

Social and Economic Pressures

Assimilation may occur because individuals pursue employment opportunities, social mobility, or access to education. Dominant-group expectations can reinforce these pressures.

Government Policies and Institutions

Policies can accelerate assimilation. School systems, legal requirements, and public messaging have historically encouraged minority groups to adopt the dominant culture’s language and norms.

These factors raise questions about the voluntary or forced nature of assimilation.

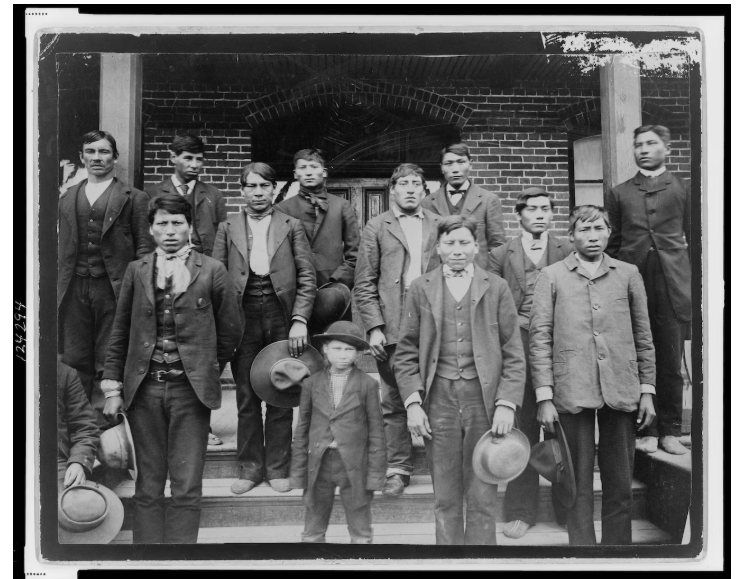

This photograph of a Native American boarding school classroom demonstrates how assimilation was enforced by suppressing Indigenous languages and cultural practices. Such institutions aimed to replace traditional identities with Anglo-American norms. The detailed historical context exceeds syllabus needs but illustrates the concept of forced assimilation clearly. Source

Voluntary Versus Forced Assimilation

Voluntary assimilation tends to occur where groups seek economic advantages, social belonging, or access to dominant-group networks. Forced assimilation is linked to coercive measures including restrictions on language use, seizure of land, or state-run residential schooling systems.

Time Scales of Assimilation

Assimilation often takes place over multiple generations. First-generation migrants may retain strong markers of their original culture, while second- or third-generation individuals may increasingly adopt dominant cultural norms.

Cultural Markers Affected by Assimilation

Assimilation can reshape numerous cultural traits:

Language: Declining use of heritage languages in favor of the dominant language.

Religion: Adoption of dominant religious practices or reduced observance of minority religious traditions.

Dress and foodways: Changes that align with majority cultural norms.

Family structure and gender roles: Adjustments that mirror dominant cultural expectations.

Language loss is especially significant because language is a key indicator of cultural maintenance and group identity.

How Assimilation Alters Landscapes

Spatial Assimilation and Residential Patterns

As assimilation progresses, residential segregation may lessen. Spatial assimilation affects residential patterns and physical landscapes.

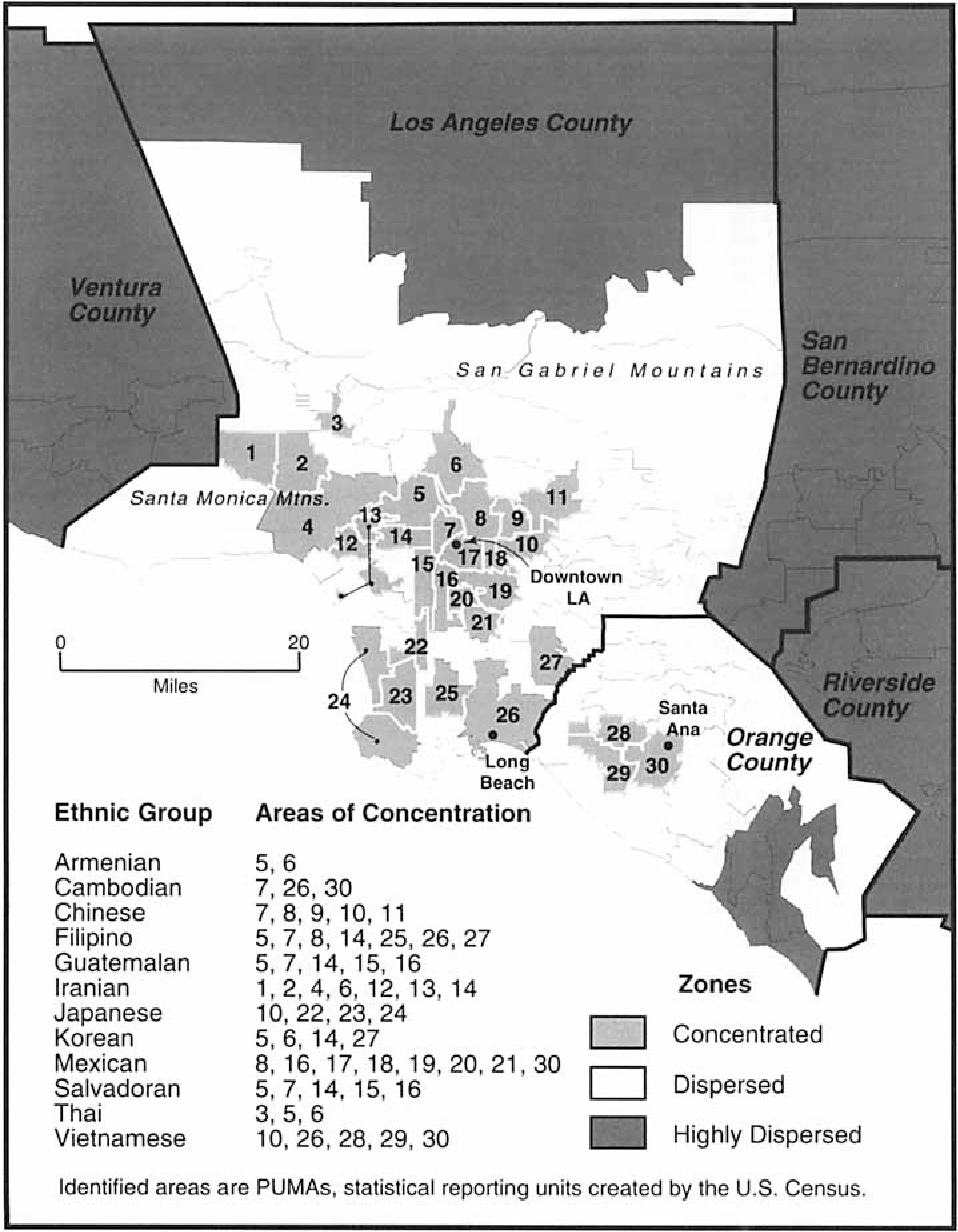

This map of ethnic concentrations in the Los Angeles region shows where immigrant groups have historically clustered. Over time, spatial assimilation can lead to more dispersed and mixed residential patterns. The full legend and dataset exceed syllabus needs, but the image illustrates spatial assimilation effectively. Source.

As minority groups move into new neighborhoods, commercial landscapes shift. Businesses serving specific cultural communities may decline or transform as assimilation increases.

Institutional and Economic Landscapes

Assimilation influences participation in schools, workplaces, and political institutions. As groups become integrated, landscapes may reflect shared cultural practices rather than distinct ethnic identities.

Resistance and Partial Assimilation

Assimilation is not always fully achieved or desired. Some groups maintain cultural identity through community organizations, places of worship, ethnic businesses, and cultural festivals. This coexistence demonstrates that assimilation can be partial, selective, and context-dependent.

FAQ

Resistance often depends on the strength of cultural identity, the presence of strong community institutions, and the level of social cohesion within the group.

Groups with well-established religious centres, schools, or media outlets tend to retain cultural distinctiveness more easily. Political marginalisation may also encourage stronger attachment to heritage culture.

Assimilation commonly produces a generational language shift.

First-generation migrants often retain their heritage language, while second-generation members become bilingual, and third-generation members tend to predominantly use the dominant language.

Loss of heritage language is accelerated when schools and workplaces favour the dominant language.

Assimilation can be voluntary when individuals seek social mobility, economic opportunity, or cultural belonging.

However, it can also result from explicit or implicit pressure, such as discrimination, legal restrictions, or the absence of institutional support for minority cultural practices.

Spatial assimilation refers to the process by which minority groups relocate into areas traditionally occupied by the dominant population.

This shift typically accompanies socioeconomic mobility, improved language proficiency, and increased intergroup contact. Over time, ethnic enclaves may become less distinct as residential mixing increases.

Intermarriage promotes cultural blending within households, which can lead to:

Adoption of dominant cultural norms

Increased use of the dominant language

Reduced transmission of heritage traditions

Children of mixed households often internalise dominant cultural practices, making intermarriage a significant driver of assimilation across generations.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks)

Explain the difference between assimilation and acculturation in the context of cultural diffusion.

Mark scheme:

• 1 mark for stating that assimilation involves a minority group adopting dominant cultural traits to the point that distinctiveness is reduced.

• 1 mark for stating that acculturation involves adopting traits while maintaining aspects of the original culture.

Question 2 (5 marks)

Using examples, analyse two ways in which assimilation can alter cultural landscapes. Your answer should consider both social and spatial aspects.

Mark scheme:

• 1 mark for identifying a social change in the cultural landscape (e.g., language shift, decline of minority religious institutions).

• 1 mark for explaining how assimilation produces this change.

• 1 mark for identifying a spatial change in the landscape (e.g., reduced ethnic clustering, transformation of ethnic commercial areas).

• 1 mark for explaining how assimilation leads to this spatial alteration.

• 1 mark for use of an appropriate example illustrating either social or spatial change.