AP Syllabus focus:

‘Types of political entities include stateless nations, multinational states, and autonomous or semiautonomous regions (such as American Indian reservations); define each and give a contemporary example.’

Political geographers examine how states and peoples interact across territory. Understanding stateless nations, multinational states, and autonomous regions clarifies how identity, governance, and space shape today’s complex political world.

Stateless Nations

Stateless nations are central to political geography because they illustrate the tension between cultural identity and political boundaries. A stateless nation is a cultural group lacking an internationally recognized, sovereign state of its own. These groups often seek political recognition, autonomy, or independence, and their situations can generate regional tensions or international concern.

Stateless Nation: A cultural group with a shared identity but without its own independent, sovereign state.

Stateless nations persist where political borders fail to align with ethnic or cultural distributions. This mismatch often results from historical empire-building, colonial boundary drawing, or deliberate state efforts to maintain control over diverse populations.

Bullet points help clarify why stateless nations matter in AP Human Geography:

• They frequently form centrifugal forces, pushing against state unity.

• Their political goals often involve recognition, autonomy, or secession.

• They illustrate the impacts of cultural diffusion, migration, and historical conquest.

A well-known contemporary example is the Kurds, a distinct cultural and linguistic group dispersed across Turkey, Iraq, Iran, and Syria.

This map highlights the distribution of Kurdish communities across multiple states, illustrating how a stateless nation occupies cultural territory that extends beyond political borders. The shading depicts settlement regions rather than sovereignty. Some included geographic labels exceed AP syllabus requirements but offer helpful locational context. Source.

Multinational States

A multinational state contains two or more cultural groups with traditions of self-determination. These states accommodate internal diversity but face challenges tied to national identity, resource distribution, and political representation.

Multinational State: A state that includes multiple national or ethnic groups with recognized political identities or historical claims to autonomy.

Multinational states may embrace multicultural policies, decentralize power, or establish mechanisms for regional representation. However, they can also experience internal conflict if cultural groups feel marginalized.

Key features typically include:

• Multiple ethnic groups with distinct identities and political interests.

• Potential for devolution if groups seek increased autonomy.

• Systems of governance that attempt to balance unity and diversity.

A contemporary example is Canada, which includes English-speaking Canadians, French-speaking Québécois, and numerous First Nations.

Autonomous and Semiautonomous Regions

Autonomous regions and semiautonomous regions demonstrate how states sometimes allow localized self-rule to manage linguistic, cultural, or historical differences. These regions vary widely in their degree of independence but maintain a formal relationship with a larger sovereign state.

Autonomous Region: A subnational area granted a high degree of self-governance from a central authority.

Autonomous status can emerge from long-standing cultural distinctions, past territorial agreements, conflict resolution processes, or constitutional arrangements. An example of a semiautonomous region in the United States is American Indian reservations, where tribal governments exercise significant authority over internal affairs, land use, and cultural preservation.

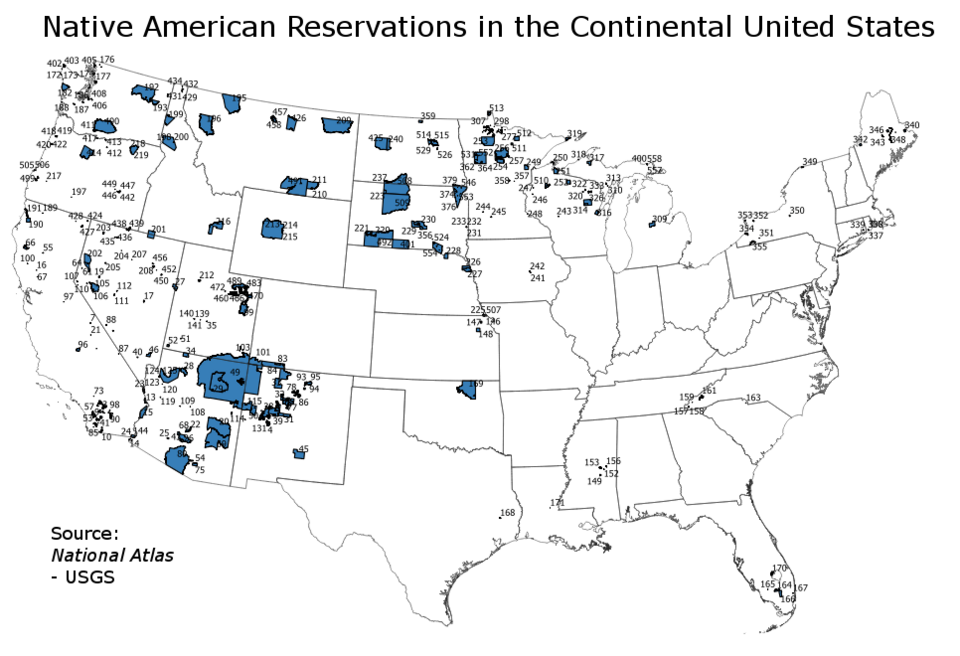

This map shows the geographic distribution of American Indian reservations, illustrating how semiautonomous regions operate within a sovereign state. The shaded areas reflect where tribal governments exercise internal authority. Some boundaries shown are historically based and include detail beyond AP syllabus requirements. Source.

Semiautonomous regions differ slightly because they possess partial, but not full, self-governance. Their powers may be constitutionally limited, and they remain more closely tied to central authority than fully autonomous regions.

Important characteristics include:

• Retention of cultural practices and governance traditions.

• Control over certain legal, educational, or economic policies.

• Recognition by the state of the region’s unique status.

These regions illustrate how political systems respond to demands for self-determination while maintaining state sovereignty.

Comparing These Political Entities

Understanding how stateless nations, multinational states, and autonomous regions differ helps reveal patterns of conflict, cooperation, and political identity.

• Stateless nations lack sovereignty but may span multiple states.

• Multinational states contain several cultural groups under one government.

• Autonomous regions exist within states but enjoy localized authority.

These categories clarify how political boundaries often fail to align with cultural landscapes and how states respond when identity and territory do not neatly overlap.

Geographic and Political Implications

The presence of these entities influences international relations, internal governance, and territorial organization.

• Stateless nations can amplify regional instability and motivate separatist movements.

• Multinational states must design institutions to manage ethnic diversity and prevent fragmentation.

• Autonomous regions illustrate attempts to maintain unity while addressing cultural or historical claims.

Political geographers study these arrangements to understand how territoriality, identity, and power interact across space. Each entity demonstrates that political boundaries are not merely lines on maps but reflect deeper cultural and historical processes shaping the modern world.

FAQ

Stateless nations often lack the political leverage, military capacity, or international backing necessary to secure independence. Existing states may also resist territorial changes that would reduce their land area or resource control.

External actors may avoid supporting new statehood to preserve regional stability.

• Geopolitical alliances

• Economic interests

• Fear of encouraging separatism elsewhere

These constraints make formal recognition difficult, even when a strong national identity exists.

Governments may implement power-sharing arrangements that give minority groups influence in national decision-making. Federalism is often used to decentralise authority and diminish conflict.

Cultural recognition policies help validate minority languages, traditions, and symbols.

• Official multilingualism

• Local control of education

• Protection of cultural heritage

These mechanisms help maintain unity while respecting distinct identities.

Autonomy can strengthen a region’s administrative capacity, identity, and political confidence. As local institutions develop, aspirations may shift from self-governance to full sovereignty.

Economic disparities can also fuel demands for independence. Wealthier autonomous regions may feel they contribute more to the central state than they receive in return, intensifying calls for separation.

Devolution typically reflects negotiated agreements shaped by history, cultural claims, and political pressure. States aim to balance regional autonomy with national cohesion.

Common devolved powers include:

• Education and cultural policy

• Local policing

• Land and resource management

Sensitive areas such as defence and foreign policy usually remain centralised to maintain unified national authority.

Cross-border autonomous regions complicate governance because neighbouring states may manage autonomy differently. Inconsistent legal frameworks can hinder movement, cultural practice, and economic coordination.

Diplomatic relations may also become strained if one state provides greater cultural or political recognition than another. These asymmetries can encourage migration, divide communities, or intensify nationalist claims.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Define a stateless nation and name one contemporary example.

Mark scheme:

• 1 mark for a correct definition (for example: a cultural or ethnic group without its own sovereign, internationally recognised state).

• 1 mark for identifying a valid contemporary example (such as the Kurds, Palestinians, or Basques).

• 1 additional mark for clarity or elaboration showing understanding (for example: noting that the group may be spread across multiple existing states).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Explain how multinational states and autonomous regions illustrate different ways that political systems manage cultural diversity. Use one example for each concept.

Mark scheme:

• 1 mark for correctly defining a multinational state.

• 1 mark for correctly defining an autonomous region.

• 1 mark for explaining how multinational states manage diversity (for example: federal structures, multicultural policies, or regional representation).

• 1 mark for explaining how autonomous regions manage diversity (for example: devolved power, cultural or legal autonomy).

• 1 mark for providing a valid example of a multinational state (e.g., Canada, the United Kingdom, Russia).

• 1 mark for providing a valid example of an autonomous or semiautonomous region (e.g., American Indian reservations, Scotland, Hong Kong depending on time period).