AP Syllabus focus:

‘Centrifugal forces may lead to failed states, uneven development, stateless nations, and ethnic nationalist movements; explain how such forces can pull a state apart.’

Centrifugal forces weaken political cohesion by intensifying divisions within a state. These forces undermine unity, challenge government authority, and increase the likelihood of fragmentation or political instability.

Centrifugal Forces and State Weakening

Centrifugal forces are forces that divide a state internally by destabilizing its political, social, or economic structures. These forces reduce national unity and can ultimately threaten the viability of the state itself. AP Human Geography emphasizes how such forces can produce failed states, uneven development, stateless nations, and ethnic nationalist movements, all of which challenge state sovereignty and territorial integrity.

When centrifugal pressures intensify, political institutions may lose legitimacy, groups may assert competing identities, and regions may seek autonomy or independence. This subsubtopic focuses on understanding the mechanisms through which centrifugal forces operate and how they may pull a state apart.

Political Centrifugal Forces

Political centrifugal forces stem from governance issues that create mistrust or conflict between people and the state.

Weak governance reduces confidence in political institutions, causing citizens to question national direction.

Corruption erodes trust and increases resentment between government elites and the general population.

Lack of political representation can lead marginalized groups to disengage, resist, or mobilize for autonomy.

Failed State: A state in which political institutions collapse or fail to provide security, services, or legitimacy to its population.

These political weaknesses can encourage separatist groups to organize, turning grievances into territorial or political demands.

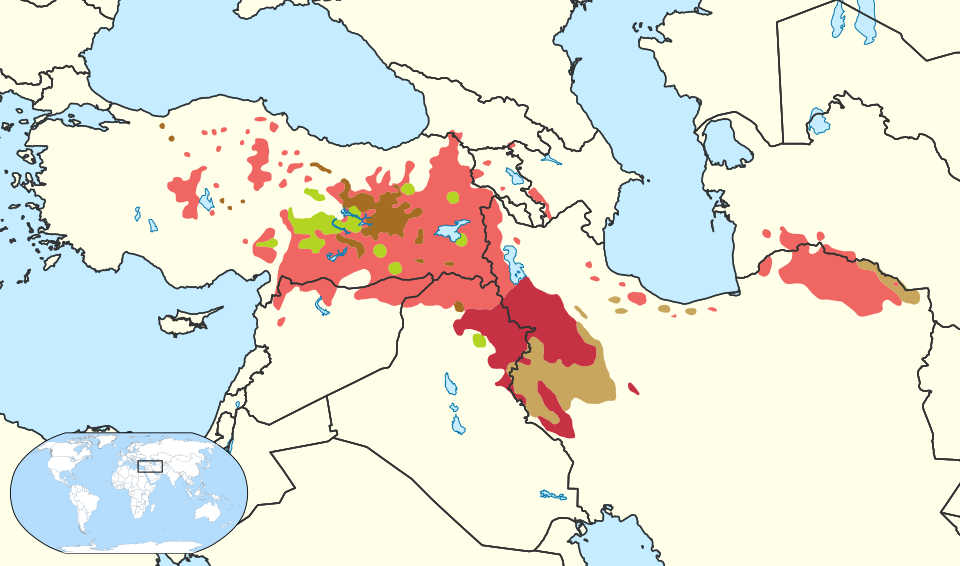

This map displays the approximate areas where different Kurdish dialects are spoken across the Middle East, illustrating how one cultural group spans several states without its own sovereign country. It reinforces the concept of a stateless nation and helps explain why Kurdish nationalism challenges existing state boundaries. The legend contains additional linguistic detail beyond syllabus requirements. Source.

Social and Cultural Centrifugal Forces

Social centrifugal forces arise from cultural heterogeneity, discrimination, or conflicting collective identities within a state. When communities perceive themselves as fundamentally different from the dominant national culture, they may develop competing loyalties.

Ethnic, linguistic, or religious diversity, when poorly managed, can escalate into deep social fragmentation.

Perceived cultural marginalization fuels resentment toward the central government.

Mistrust between groups can erode shared national identity and social cohesion.

Stateless Nation: A cultural or ethnic group that lacks an independent state and is not the majority population in any existing state.

Stateless nations often become focal points of centrifugal pressure because they may seek self-determination or reject the legitimacy of national boundaries drawn without cultural considerations.

Ethnic Nationalism as a Centrifugal Force

Ethnic nationalism, an identity-based movement asserting that a particular ethnic group deserves sovereignty, can intensify internal conflict. When ethnic nationalism grows, political borders may be challenged by groups attempting to align national identity with territorial control.

Ethnic nationalist groups may demand regional autonomy, greater cultural rights, or complete independence.

Conflicts may escalate into violence if the state rejects these demands.

Rising nationalism in one group may provoke counter-nationalism in others, accelerating fragmentation.

Ethnic nationalist movements often produce contested political boundaries, which reinforce centrifugal pressures by encouraging regions to question their allegiance to the state.

Economic Centrifugal Forces and Uneven Development

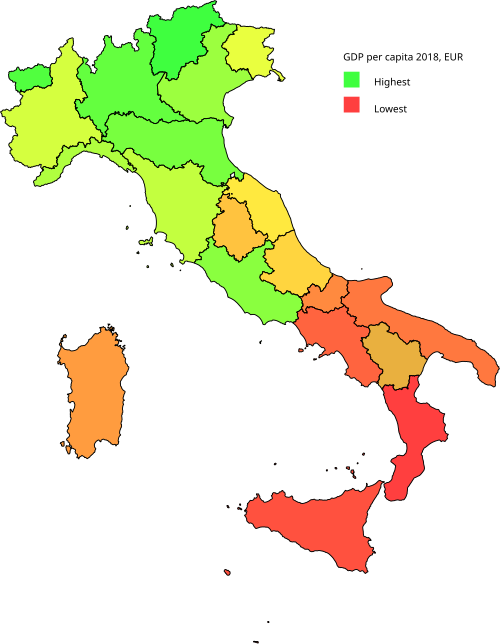

Economic inequality, particularly uneven development across regions, is one of the strongest centrifugal forces identified in AP Human Geography. When some regions experience prosperity while others face chronic poverty, political tensions and resentment intensify.

This map shows GDP per capita by province in Italy using color shading to distinguish wealthier and poorer regions. It visually demonstrates how economic disparities create uneven development that can become a centrifugal force. The map contains additional detail on individual provinces, which exceeds syllabus requirements but supports broader regional comparison. Source.

Prosperous regions may feel exploited by the central government and seek greater fiscal control.

Poorer regions may feel neglected or marginalized due to a lack of investment.

Migration patterns may shift toward wealthier areas, intensifying demographic and political imbalances.

These disparities create a geography of inequality that weakens national cohesion and fosters demands for redistribution, regional autonomy, or secession.

Centrifugal Forces and Territorial Fragmentation

Centrifugal forces weaken territorial integrity by challenging the state’s ability to maintain control over its land and population. Increasing demands for autonomy, identity-based separatism, and economic grievances can cumulatively push a state toward fragmentation.

Regions may pursue devolution, requesting greater local authority.

In extreme cases, internal divisions can create breakaway regions that function independently.

Violence or civil conflict may reduce the state’s territorial control.

Ethnic Nationalist Movement: A political or social movement in which an ethnic group seeks greater autonomy, recognition, or independence based on shared cultural identity.

Territorial fragmentation is reinforced when centrifugal forces overlap—such as when a region that is economically distinct is also culturally separate and politically underrepresented.

How Centrifugal Forces Pull a State Apart

Centrifugal forces weaken unity by undermining trust, creating competing identities, and fueling conflict between regions and the central government. These forces challenge the shared symbols, institutions, and economic relationships that bind states together. When centrifugal pressures escalate, sovereignty becomes contested, borders become unstable, and the likelihood of political disintegration increases.

Key pathways through which centrifugal forces weaken states include:

Loss of legitimacy, where the government appears ineffective or corrupt.

Competing identities, which reduce adherence to national identity.

Territorial challenges, where regions no longer recognize central authority.

Escalating grievances, which can transform tensions into open conflict.

As the AP specification emphasizes, these combined effects may produce failed states, uneven development, stateless nations, and ethnic nationalist movements—all powerful indicators of state weakening and potential fragmentation.

FAQ

Economic disparities become centrifugal when they are:

Persistent over generations

Spatially clustered in identifiable regions

Perceived as the result of government neglect or exploitation

These conditions encourage groups to question the fairness of state policies and may drive demands for autonomy or redistribution.

Communication networks can amplify centrifugal forces by enabling marginalised groups to share grievances, mobilise supporters, and coordinate protests.

They also allow separatist or nationalist movements to publicise their cause internationally, gaining visibility and potentially external support.

Governments can reduce centrifugal pressures by adopting:

Devolution or regional autonomy arrangements

Fairer distribution of resources

Anti-corruption reforms

Policies that recognise cultural or linguistic minorities

These measures can strengthen trust in national institutions and make unity more appealing than separation.

Centrifugal forces are specific drivers that pull a state apart by intensifying internal divisions, while general political instability may result from short-term crises or temporary governance issues.

Centrifugal forces usually stem from structural or long-standing tensions, such as entrenched ethnic divisions or persistent economic inequality, which continually erode national cohesion.

Some diverse states remain cohesive because they invest heavily in inclusive governance, equitable development, and recognition of minority rights.

States may also strengthen unity through shared institutions, widely accepted national symbols, and political systems that encourage power-sharing across regions or ethnic groups.

Practice Questions

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Using examples, analyse how economic inequality and ethnic nationalism can act together to increase centrifugal pressures within a state.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for describing economic inequality as uneven development between regions or groups.

1 mark for describing ethnic nationalism as political mobilisation around an ethnic identity seeking autonomy or independence.

1 mark for explaining how economic inequality can fuel resentment or marginalisation.

1 mark for explaining how ethnic nationalism can challenge state unity or accepted borders.

1 mark for analysing how these two forces may reinforce one another (e.g., economically marginalised ethnic groups pursue autonomy; wealthier regions seek separation).

1 mark for using a clear, relevant real-world example to support the analysis.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Define the term centrifugal forces and explain one way in which they can contribute to the weakening of a state.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for a clear definition of centrifugal forces as forces that divide or destabilise a state.

1 mark for identifying one pathway through which they weaken a state (e.g., ethnic conflict, weakening legitimacy, uneven development).

1 mark for explaining how this pathway contributes to state weakening (e.g., reduced cohesion, increased separatism, loss of territorial control).