AP Syllabus focus:

‘Political power is illustrated by neocolonialism, shatterbelts, and choke points; explain how each creates leverage, vulnerability, or conflict in key places.’

Political power is unevenly distributed across global space, and states use economic influence, regional instability, or strategic locations to gain leverage, assert authority, and control key interactions.

Neocolonialism

Neocolonialism refers to indirect control that powerful states or corporations exert over less powerful countries through economic, political, or cultural pressures rather than direct territorial rule.

Neocolonialism: The indirect use of economic, political, or cultural pressures by powerful states to influence or control weaker, usually formerly colonized, states.

Neocolonial relationships often emerge because historical patterns of dependency continue after the end of formal colonial rule.

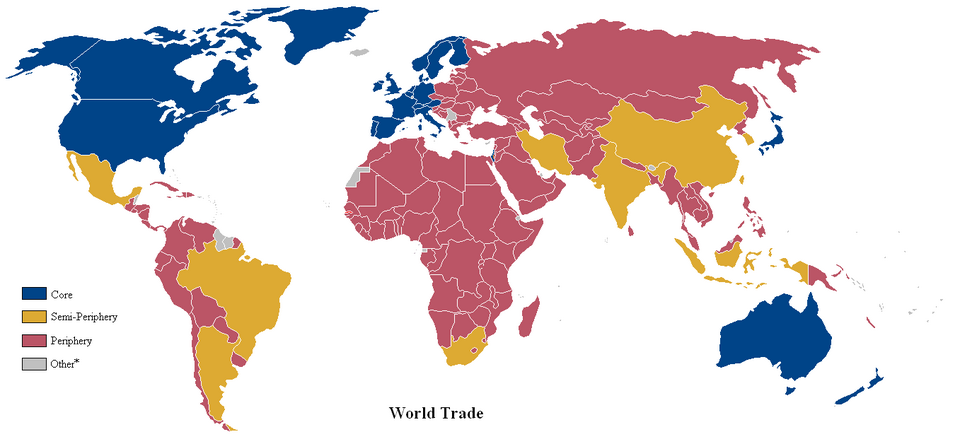

This map shows the core, semi-periphery, and periphery structure of the global economy, illustrating how trade relationships support uneven power. It reinforces how core states can maintain neocolonial influence through economic dominance. The map includes categorization details not required by the syllabus but useful for visualizing global dependency patterns. Source.

Unlike classic colonialism, which relied on military occupation, neocolonialism operates through influence, loans, trade imbalances, and international institutions.

Mechanisms of Neocolonial Control

• Foreign investment dominance — When multinational corporations from core countries determine economic activity in developing states.

• Debt dependency — High-interest loans from wealthier states or international financial institutions shape political decisions.

• Unequal trade relationships — Peripheral countries export low-value raw materials while importing high-value manufactured goods.

• Cultural and media influence — Global cultural diffusion reinforces political and economic power hierarchies.

These mechanisms create leverage because the more powerful state exerts control without formal governance, shaping domestic policy or resource access. They also produce vulnerability when the weaker state becomes dependent on external capital or markets.

Contemporary Illustrations

• Large infrastructure financing that gives creditor states influence over ports, mineral rights, or political alignment.

• Foreign agribusinesses acquiring major land holdings in developing regions, reshaping local economies.

Shatterbelts

A shatterbelt is a region caught between the strategic interests of more powerful external states, creating chronic instability, conflict, and competition for influence.

Shatterbelt: A region of persistent instability located between stronger, rival powers whose competing interests foster conflict and fragmentation.

Shatterbelts arise in places where geography, cultural divisions, and great-power rivalries intersect.

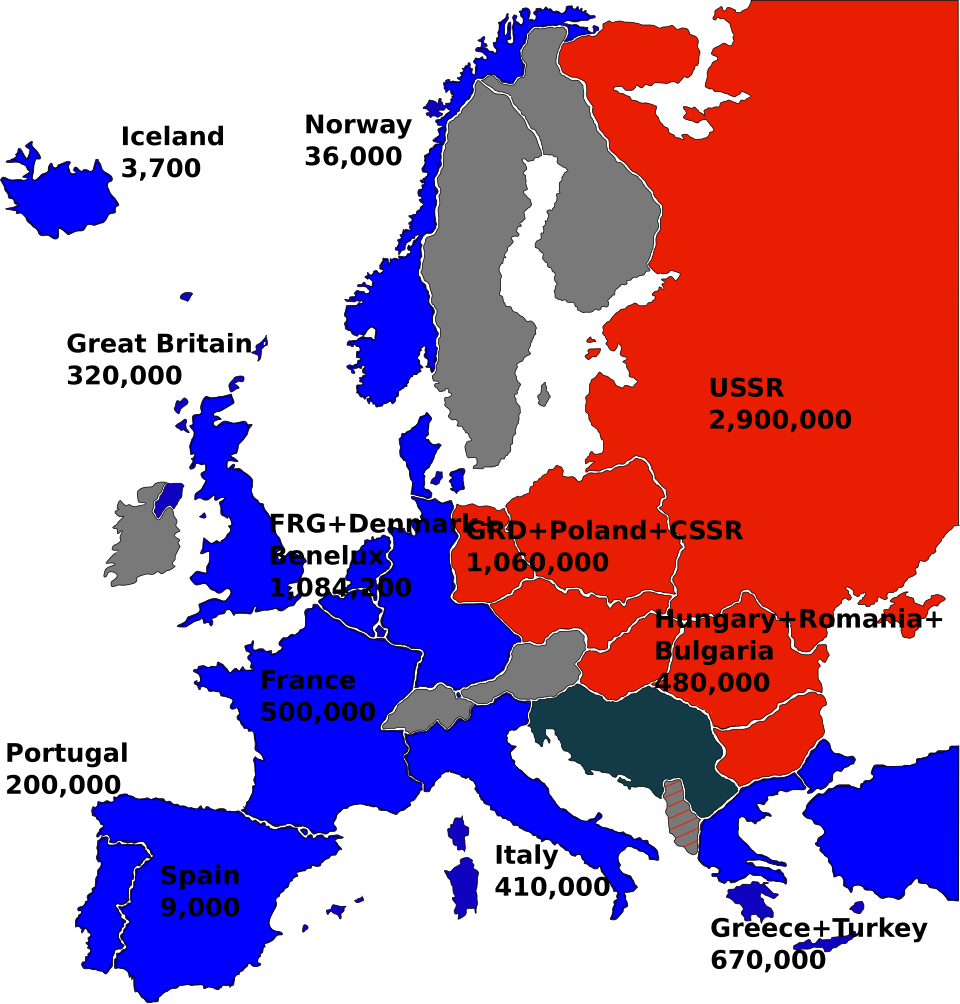

This map depicts NATO and Warsaw Pact alliances during the Cold War, showing Eastern Europe positioned between two rival blocs. It illustrates a classic shatterbelt shaped by ideological and geopolitical conflict. The map also includes additional alliance and labeling detail not required by the AP syllabus but helpful for visualizing competing pressures in the region. Source.

A sentence before lists ensures conceptual flow.

Key Characteristics of Shatterbelts

• Geopolitical tension — Rival states compete for influence or alliance in the region.

• Internal fragmentation — Diverse ethnic or political groups face intensified pressures.

• Persistent conflict zones — Borders and governance rarely stabilize.

• External intervention — Outside powers provide military, economic, or political support to opposing groups.

Why Shatterbelts Matter in Political Geography

• They illustrate how external power rivalries shape internal political geography.

• They create vulnerability, as states inside a shatterbelt may experience territorial loss, civil conflict, or forced alignment.

• They become sites where supranational organizations or alliances intervene to maintain stability or secure influence.

Choke Points

A choke point is a narrow, strategic passage—usually maritime—that is critical for global trade or military movement.

Choke Point: A narrow strategic passageway, such as a strait or canal, whose control is essential for the movement of goods, resources, or military forces.

Choke points create leverage because a state or organization that controls them gains disproportionate power over international trade, energy flows, and naval operations.

Strategic Significance of Choke Points

• Economic leverage — Control over maritime traffic allows states to regulate access to critical shipping routes.

• Military advantage — Navies can restrict enemy movement or secure their own fleet’s mobility.

• Global market vulnerability — Disruptions can drastically affect commodity prices, especially oil and natural gas.

• Security tensions — Rival states may militarize nearby territory to secure uninterrupted passage.

Why Choke Points Create Vulnerability

• They can easily be blocked or disrupted by conflict, piracy, or infrastructure failure.

• Their narrow geography means even minor attacks or accidents can halt global flows.

• States dependent on the route become susceptible to pressure from whoever controls it.

Comparative Geographic Impacts

How Neocolonialism Creates Leverage

• Influencing the economic decisions of developing states.

• Shaping domestic policy through conditional aid or investment.

• Securing access to valuable resources without territorial conquest.

How Shatterbelts Produce Vulnerability

• States face internal turmoil fueled by external rivalries.

• Borders remain unstable or contested.

• Political independence may be undermined by foreign intervention.

How Choke Points Generate Conflict

• Competition to secure control or influence over strategic passages.

• Heightened military presence increases the likelihood of confrontation.

• International disputes emerge over navigation rights, security measures, or territorial claims.

Through these three concepts—neocolonialism, shatterbelts, and choke points—this subsubtopic illustrates how political power is deeply spatial, shaping global patterns of leverage, vulnerability, and conflict.

FAQ

Infrastructure projects can create long-term financial dependence when loans, construction, and management are controlled by foreign states or corporations.

This dependence may allow external actors to influence domestic policy, secure resource rights, or obtain favourable trade terms.

• Host states may struggle to repay large loans.

• Infrastructure ownership or operation may shift to the creditor state.

• Political alignment can shift toward the dominant investor.

Shatterbelts sit between powerful rival states, so shifts in global alliances or geopolitical objectives can quickly alter the pressures placed on them.

Competing powers often seek influence through military presence, aid, or political support, making internal stability highly sensitive to external decisions.

Ethnic diversity or contested borders within the region often exacerbates this vulnerability.

Militarisation occurs when states perceive a threat to the security or reliability of the passage.

Common triggers include:

• Piracy or terrorism in nearby waters

• Rival states disputing access or territorial claims

• Strategic interest in safeguarding energy shipments

• Pressure to deter adversaries or demonstrate naval power

States may establish bases, deploy fleets, or enter security agreements to protect the choke point.

Technological advancements can either reduce or heighten reliance on choke points.

For example, larger vessels or alternative shipping routes may reduce congestion, while improvements in surveillance and weapons systems can make it easier to monitor or control these passages.

Digital mapping and satellite imagery also allow states to track movement more closely, increasing their ability to exert influence over strategic waterways.

Yes. Internal regions can experience shatterbelt-like pressure when domestic groups align with different external powers.

This occurs when:

• Ethnic or political factions receive support from foreign states

• Border regions become zones of rival influence

• Internal conflicts attract international intervention

While not traditionally classified as shatterbelts, such areas display similar instability driven by external geopolitical competition.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain how a maritime choke point can give a state geopolitical leverage in the contemporary world political system.

• 1 mark for identifying that choke points are narrow strategic passages essential for global trade or resource flows.

• 1 mark for explaining that control of a choke point allows a state to influence or restrict movement of goods, particularly energy resources.

• 1 mark for linking this control to geopolitical leverage, such as the ability to pressure other states, protect trade, or shape security dynamics.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Using specific examples, analyse how neocolonialism and shatterbelts create vulnerability for states within the global political system.

• 1 mark for defining neocolonialism as indirect economic, political, or cultural control by powerful states over weaker states.

• 1 mark for explaining a mechanism of neocolonial vulnerability (e.g., debt dependency, foreign economic dominance, or unequal trade).

• 1 mark for providing a relevant real-world example showing neocolonial influence.

• 1 mark for defining a shatterbelt as a region caught between powerful external rivals, leading to instability.

• 1 mark for explaining how great-power competition intensifies internal conflict or political fragmentation in shatterbelt regions.

• 1 mark for providing a relevant example of a shatterbelt and linking it to state vulnerability.