AP Syllabus focus:

‘Types of political boundaries include superimposed and geometric boundaries; define each and explain how imposed or straight-line borders can affect communities.’

Political boundaries shape how states interact and govern. Understanding superimposed and geometric boundaries reveals how imposed or straight-line borders affect societies and spatial relationships today.

Superimposed and Geometric Boundaries in Political Geography

Superimposed and geometric boundaries represent two important categories of political borders that strongly influence spatial organization, governance, and cultural landscapes. Each type is defined by distinct processes of creation, and both have significant consequences for the communities they divide or connect.

Defining Superimposed Boundaries

A superimposed boundary is introduced into a region by an external power—often without considering existing cultural, ethnic, or political patterns. Because they are drawn by outsiders, these boundaries frequently disrupt long-standing social structures and create lasting geopolitical challenges.

Superimposed Boundary: A political boundary placed over an area by an outside authority, disregarding existing cultural or ethnic divisions.

Superimposed boundaries are closely linked to the legacies of colonialism, imperialism, and external territorial claims.

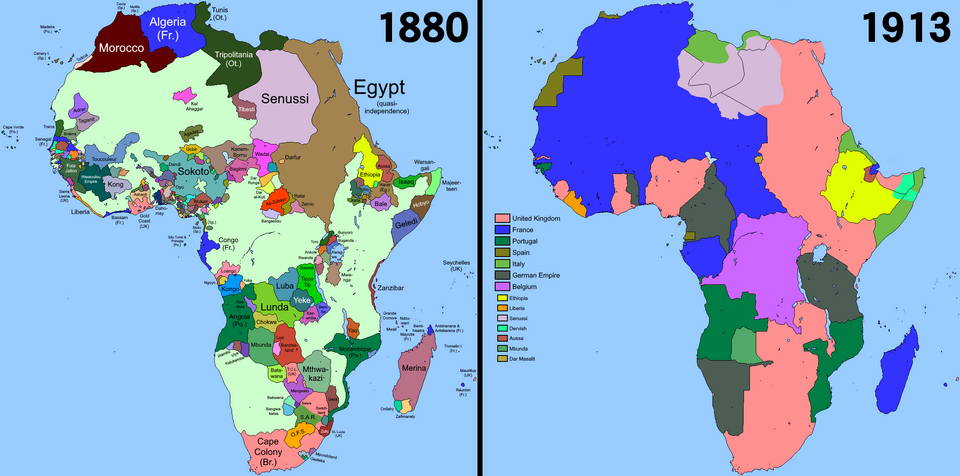

This pair of maps compares Africa in 1880 and 1913, illustrating how European powers imposed superimposed boundaries during colonial rule. These externally drawn borders cut across cultural regions and reorganized territorial control. The map includes additional historical detail about specific colonial empires not required by the AP syllabus but useful for understanding the origins of imposed boundaries. Source.

They often persist long after the outside force has departed, shaping national identities, political conflict, and patterns of development.

Superimposed boundaries affect communities in several important ways:

Cultural fragmentation: Groups with shared languages, religions, or histories may be separated into different states.

Political tension: Divided ethnic groups may challenge national borders, pursue autonomy, or engage in separatist movements.

Uneven development: Arbitrary borders can consolidate resources in one state while limiting access in another.

Geopolitical instability: Fragmented groups may pull neighboring states into regional disputes.

Superimposed boundaries frequently influence population movement as well. Communities may migrate to avoid conflict, improve economic opportunity, or preserve cultural ties disrupted by imposed lines.

Defining Geometric Boundaries

A geometric boundary is a political border drawn along a straight line or arc, usually based on latitude, longitude, or a grid-system reference.

This satellite-based image shows a section of the U.S.–Canada border following the 49th parallel, a classic geometric boundary. The almost perfectly straight line demonstrates how geometric borders rely on abstract coordinate systems rather than physical or cultural features. The image includes additional elements such as nearby roads and facilities that exceed syllabus requirements but help illustrate modern border landscapes. Source.

Rather than reflecting cultural or physical landscapes, geometric boundaries rely on abstract spatial coordinates.

Geometric Boundary: A political boundary defined by straight lines or geometric shapes, often based on latitude, longitude, or survey systems rather than physical or cultural features.

How Superimposed and Geometric Boundaries Affect Communities

The AP syllabus emphasizes the importance of understanding how boundaries—especially imposed or straight-line ones—shape human geography. These border types influence communities in several key ways.

1. Disruption of Cultural Cohesion

Both superimposed and geometric boundaries often ignore ethnolinguistic and cultural patterns. When borders cut through shared cultural regions, people may experience:

Loss of unified governance

Division of family networks and trade routes

Emergence of minority groups within new states

Tension between divided cultural groups and central governments

2. Formation of Conflict Zones

Superimposed boundaries can generate conflict when external powers disregard territorial claims or historical ties. Geometric boundaries, while neutral in form, may still bisect groups or resources, provoking disputes over:

Land ownership

Access to water, minerals, or agricultural zones

Sovereignty claims

National identity

These tensions may contribute to border militarization, population displacement, or long-term regional instability.

3. Administrative Challenges

When states contain diverse and divided populations created by superimposed or geometric boundaries, governments face challenges such as:

Designing equitable political representation

Managing competing nationalisms

Providing public services to fragmented communities

Maintaining internal security

Superimposed boundaries, in particular, may force governments to navigate competing cultural and political interests within the same territorial space.

4. Economic Implications

Boundaries that split regions without regard for economic patterns can influence development by:

Disrupting traditional trade networks

Creating disparities in access to natural resources

Forcing states to negotiate new economic relationships

Producing border cities that become hubs or conflict zones depending on stability

Geometric boundaries can carve straight lines across deserts, forests, or resource-rich zones, giving rise to disputes over extraction rights or management responsibilities.

Spatial Patterns and Interpretation of Border Effects

Understanding these boundary types helps geographers analyze spatial patterns and their real-world implications. Superimposed boundaries often produce irregular geopolitical landscapes, while geometric boundaries create visually orderly but socially complex regions. In both cases, the borders affect:

Migration flows

Settlement patterns

Territorial identity

National cohesion

Analyzing maps with superimposed or geometric boundaries allows students to identify where and why conflict, cooperation, or cultural divergence may occur.

The Importance of Boundary Types in Human Geography

The AP Human Geography framework emphasizes that political boundaries do more than mark territory—they shape societies. Superimposed and geometric boundaries clearly illustrate how borders created without regard to human patterns can profoundly influence the political, cultural, and economic realities of communities that live within and across them.

FAQ

Superimposed boundaries often become embedded in state institutions, legal systems, and administrative divisions, making them difficult to change without major political upheaval.

They are also reinforced by international recognition of existing borders, as states are reluctant to support changes that could set precedents elsewhere.

Additionally, populations may adapt to the imposed borders over generations, making alternative arrangements politically or socially complex to negotiate.

Geometric boundaries are easier to survey and map in areas where physical features are limited or where the landscape is difficult to traverse.

They avoid disputes over natural landmarks that might shift over time, such as rivers with variable courses.

Governments or colonial powers often used geometric lines to quickly allocate large tracts of territory without detailed local knowledge.

Superimposed boundaries can place multiple linguistic groups within a single political unit, increasing internal diversity.

This may lead to:

competition for official-language status

uneven access to education in minority languages

pressure on smaller language groups to assimilate

In some cases, linguistic fragmentation can become a driver of regional political movements.

Geometric boundaries may become disputed when they cut across valuable resources, strategic locations, or communities with strong identities.

They are also contested when the original surveying was inaccurate or when states interpret coordinate-based definitions differently.

Shifts in population or economic priorities may increase the significance of what was originally a neutral or unused boundary line.

Advances such as satellite imagery, GPS, and digital mapping make it easier for states to monitor and maintain geometric boundaries accurately.

They reduce uncertainty about the boundary’s exact location, helping prevent accidental encroachments.

Improved surveillance and border infrastructure can also increase state presence in remote areas where geometric boundaries were previously difficult to enforce.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Define a geometric boundary and explain why such boundaries may create challenges for communities living along them.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Award up to 3 marks:

1 mark for a correct definition of a geometric boundary (a border based on straight lines, latitude/longitude, or grid systems rather than physical or cultural features).

1 mark for identifying one challenge, such as dividing cultural or ethnic groups.

1 mark for explaining why this creates difficulties (for example, causes tensions, disrupts daily interactions, or complicates governance).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Using specific geographical reasoning, analyse how superimposed boundaries created during colonial rule continue to influence political conflict and cultural fragmentation in contemporary states.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Award up to 6 marks:

1 mark for stating that superimposed boundaries were imposed by external powers, often during colonialism.

1 mark for explaining that these boundaries ignored pre-existing cultural, ethnic, or political patterns.

1 mark for describing how this can lead to divided groups pursuing autonomy, resisting state authority, or experiencing identity-based tension.

1 mark for linking superimposed boundaries to contemporary political conflict (for example, civil wars, separatist movements, or border disputes).

1 mark for explaining cultural fragmentation, such as the grouping of diverse ethnicities within a single state.

1 mark for clear, geographically informed analysis that uses accurate terminology and demonstrates understanding of spatial processes.