AP Syllabus focus:

‘Societal effects include changing diets, women’s roles in agricultural production, and shifts in agriculture’s economic purpose.’

Agricultural practices reshape societies by influencing what people eat, who performs agricultural labor, and how farming fits within broader economic systems across diverse cultural landscapes.

Changing Diets and Agricultural Practices

Dietary patterns evolve as agricultural systems change, and these shifts reflect broad social, economic, and cultural transformations. As societies transition from predominantly subsistence agriculture to more commercial agriculture, the diversity, availability, and nutritional value of foods often shift.

Globalization and Diet Convergence

Global agricultural trade promotes a growing similarity in diets across world regions.

Increased production of cash crops—crops grown primarily for sale rather than direct consumption—often reduces local reliance on traditional staples.

Expanded supply chains make processed foods widespread, encouraging rising consumption of sugar, fats, and calorie-dense products.

Urbanization increases access to global food markets and decreases consumption of locally grown produce.

Cash Crop: A crop produced chiefly for sale in the market rather than for a farmer’s direct consumption.

These dietary changes influence public health, sometimes increasing rates of obesity or micronutrient deficiencies depending on access, affordability, and food distribution networks.

MyPlate illustrates a balanced diet by dividing a plate into fruits, vegetables, grains, and protein, with a side circle for dairy. It represents one public-health response to diet-related problems that emerge as food systems shift toward processed and calorie-dense foods. While based on U.S. guidelines, it helps visualize how agricultural production supports healthier or less healthy dietary patterns. Source.

Agricultural Shifts and Nutrition

Changes in food production alter the nutritional landscape.

Movement toward monocropping can reduce dietary diversity.

Commercial livestock expansion increases availability of meat and dairy, reshaping protein consumption patterns.

Subsistence-based communities experiencing agricultural modernization may face reduced food security if traditional foods decline.

Gender Roles in Agricultural Production

Women play central roles in global food systems, but their responsibilities and opportunities vary widely by region, culture, and agricultural structure. Gendered divisions of labor shape who plants, harvests, markets, and manages agricultural products.

Regional Variation in Women’s Roles

Women’s agricultural labor is influenced by social norms, land rights, and economic systems.

In many subsistence farming regions of sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, women perform a majority of planting, weeding, and household food preparation.

Women farmers in India collaborate in a crop field, reflecting the central role women play in planting, managing, and harvesting in many agrarian societies. The image highlights how women’s labor sustains subsistence and commercial production, even when they lack equal access to land and credit. Although taken in a specific regional context, it visually represents broader global patterns of women’s agricultural work discussed in this topic. Source.

In commercial agricultural zones, women increasingly participate in processing, packaging, and low-wage labor within global supply chains.

Access to land ownership, credit, and agricultural technology often remains unequal, limiting productivity and economic independence.

Subsistence Farming: A form of agriculture in which farmers grow primarily for their own consumption rather than for sale.

Gendered divisions of labor also influence migration patterns. As men migrate to cities for industrial work, women frequently assume greater responsibility for rural agricultural production, a trend known as the feminization of agriculture.

Structural Barriers and Opportunities

Women’s access to agricultural resources is shaped by factors such as inheritance laws, property rights, and education.

Limited access to tools, capital, and technological inputs constrains productivity.

Development programs increasingly emphasize women’s agricultural training, microfinance, and cooperative farming initiatives.

Improving women’s participation in decision-making enhances food security for households and communities.

Shifts in Agriculture’s Economic Purpose

Agriculture’s role in society evolves as economies grow, markets expand, and global demand changes. A transformation in the economic purpose of farming—from local subsistence to global commercial integration—reshapes rural landscapes and social structures.

Transition from Subsistence to Commercial Models

Many regions shift from small-scale, low-input subsistence production to profit-oriented commercial agriculture.

The rise of export-oriented production aligns agricultural activity with global markets rather than local needs.

Farmers may specialize in a single high-value commodity to maximize profit, increasing dependence on international price fluctuations.

Mechanization and technology reduce labor demands, contributing to rural depopulation as workers seek employment elsewhere.

Market Forces and Rural Change

Economic restructuring affects how communities use land, organize labor, and interact with global supply chains.

Government policies such as subsidies, price supports, or trade agreements influence what crops farmers choose to grow.

Expanded agribusiness consolidates farmland, shifting control from individual farmers to large corporations.

Participation in global commodity chains requires meeting international standards for quality, safety, and production efficiency.

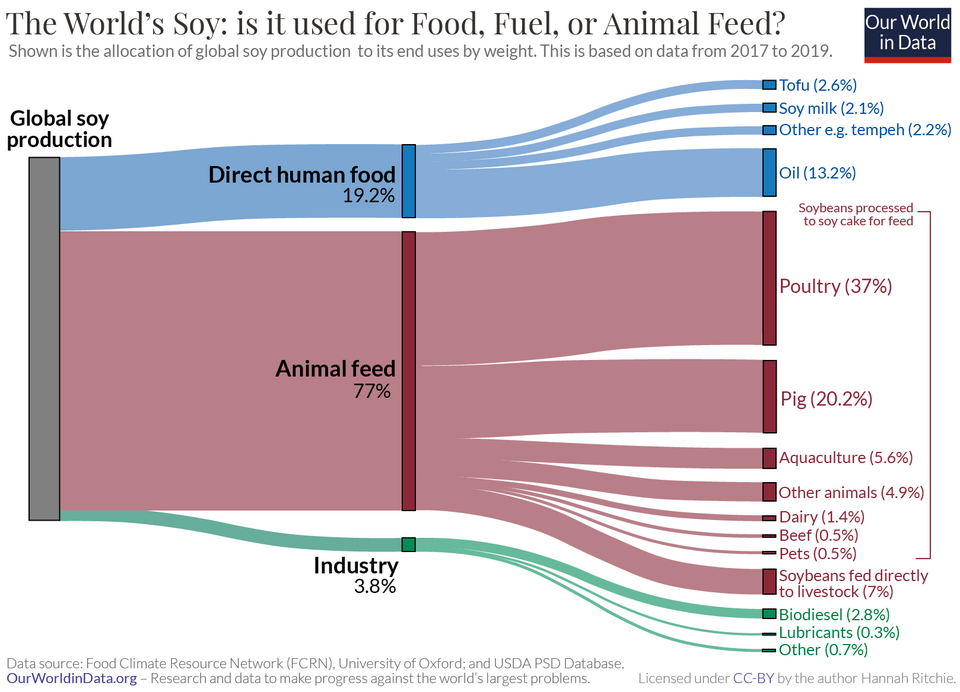

This diagram maps global soybean production from farms to final uses such as animal feed, vegetable oils, and direct food products. It demonstrates how a single crop can be oriented primarily toward export markets and livestock industries rather than local subsistence. The figure includes quantitative detail beyond the syllabus, but these additional percentages simply deepen the illustration of how agricultural production is tied to complex global commodity chains. Source.

Commodity Chain: The network of activities, workers, and processes involved in the creation, transportation, and sale of a product from origin to end consumer.

These economic transformations influence livelihoods, creating opportunities for income while also increasing vulnerability to market instability, climate shocks, and global economic shifts.

Social Implications of Economic Change

Shifts in agriculture’s economic purpose have far-reaching societal effects.

Local food systems may weaken when export-oriented production reduces availability of staple crops.

Income inequality can widen if commercial farm profits concentrate among landowners rather than laborers.

Rural-to-urban migration increases as fewer workers are needed in mechanized agricultural sectors.

Agriculture continually shapes and is shaped by social conditions, influencing diets, gender dynamics, and the economic foundations of communities.

FAQ

Cultural traditions often determine which foods are most valued, but agricultural modernisation can alter availability and affordability. When traditional crops decline due to commercial farming, cultural food practices may be weakened or adapted.

Some societies respond by substituting imported or processed foods that fit similar cooking styles, while others preserve traditional dishes but rely on different ingredients. These cultural negotiations shape how diets evolve during agricultural transitions.

Women benefit economically only when commercialisation expands roles they can access. This depends on land rights, control of income, and access to markets.

Women are more likely to gain economic power when:

They can legally own or inherit farmland.

They participate in cooperatives or producer groups.

Local supply chains allow women to sell crops directly rather than through intermediaries.

Without these conditions, commercialisation may strengthen male-dominated economic structures.

The extent of male migration, the structure of rural labour markets, and cultural expectations about women’s work all shape where feminisation develops.

Regions with significant male urban migration and strong subsistence needs rely more on women’s labour. In contrast, areas with heavy mechanisation or large commercial farms often reduce the need for women’s on-farm work, leading to less feminisation despite similar economic pressures.

Farmers shift toward commercial crops when international buyers create stable, profitable markets. Global demand for items such as coffee, cocoa, and soy encourages monocropping and export-oriented production.

However, when market prices fluctuate or transportation networks are weak, farmers may maintain subsistence plots as a buffer. By balancing risk and income, households decide how much land to allocate to commercial versus consumption crops.

Dependence on unpaid female labour can limit women’s educational attainment and political participation, reinforcing gender inequality.

Households may experience:

Reduced diversification of livelihoods, as women have fewer opportunities outside agriculture.

Greater food security vulnerability if women are overburdened and unable to maintain production.

Generational impacts, as daughters may be required to assist in farming at the expense of schooling.

These effects highlight how labour expectations shape long-term social development.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which shifting agricultural practices can lead to changes in dietary patterns within a society.

Question 1

1 mark for identifying a valid link between agricultural practices and diet (e.g., commercialisation increasing processed food availability).

1 mark for explaining how the change in practice affects the type, diversity, or nutritional value of food consumed.

1 mark for providing an additional detail, such as referencing market access, food affordability, or reduced reliance on traditional staples.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Analyse how gender roles in agriculture can influence both household food security and the wider economic purpose of farming in developing regions.

Question 2

Award marks as follows:

1 mark for identifying a gendered division of labour in agriculture (e.g., women performing most subsistence food production tasks).

1 mark for explaining how women's agricultural labour contributes to household food security (e.g., through managing staple crops or maintaining dietary diversity).

1–2 marks for analysing how limited access to land, credit, or technology affects productivity and economic roles.

1–2 marks for linking gender dynamics to broader economic purpose (e.g., feminisation of agriculture shifting labour patterns, or commercial agriculture marginalising women in value chains).