AP Syllabus focus:

‘Early hearths of domestication arose in the Fertile Crescent and in the Indus River Valley, Southeast Asia, and Central America.’

Early agricultural hearths mark the first places where humans domesticated plants and animals, creating dependable food sources that enabled permanent settlements, population growth, and complex cultural development.

Hearths of Domestication: Foundations of Early Agriculture

The study of hearths of domestication focuses on the specific world regions where people first began cultivating plants and taming animals for sustained human use.

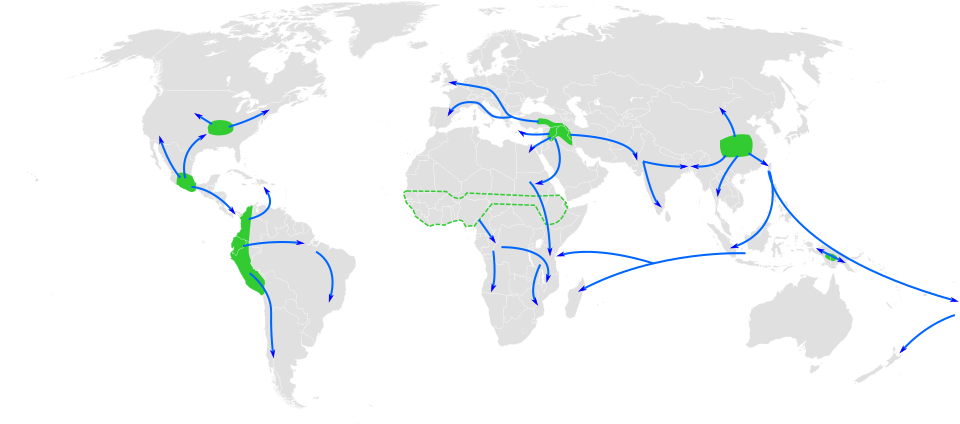

This world map highlights early centers where agriculture emerged and shows the general routes by which farming spread in prehistory. It emphasizes regions such as the Fertile Crescent and Central Mexico as key hearths of domestication for crops and livestock. The map also includes additional centers beyond those listed in the syllabus, offering broader context. Source.

These hearths—geographically distinct yet culturally transformative—represent some of humanity’s earliest innovations in food production. By shifting from foraging to food cultivation, societies altered landscapes, developed new technologies, and established the basis for long-term settlement. Each major hearth contributed unique domesticated species that later diffused across continents through migration, trade, and cultural interaction.

Understanding Domestication

Domestication refers to the selective breeding of plants or animals to make them more useful to humans, a process that gradually changed species’ traits over generations.

Domestication: The process by which humans alter plant or animal species through controlled breeding so traits become more advantageous for food, labor, or other human uses.

Domestication occurred independently in several regions, often driven by environmental conditions, species availability, and cultural needs. These hearths formed the agricultural foundations for later civilizations.

The Fertile Crescent: One of the Earliest Agricultural Hearths

The Fertile Crescent, located in Southwest Asia, is widely recognized as one of the world’s earliest and most influential agricultural hearths.

This map shows the extent of the Fertile Crescent, including the Nile Valley, the Levant, and Mesopotamia. It reinforces the location of a major hearth where wheat, barley, lentils, sheep, goats, and cattle were early domesticated. The map includes surrounding modern regions, adding geographic context beyond the syllabus scope. Source.

Its favorable climate, diverse ecology, and presence of naturally occurring grains made it ideal for early experimentation with cultivation. The region supported some of the first permanent settlements and contributed significantly to the global spread of agriculture.

Key Domesticated Plants and Animals

The Fertile Crescent produced many of the world’s first staple crops and livestock species.

Wheat (including einkorn and emmer varieties)

Barley, essential for bread and early fermented beverages

Lentils and peas, important sources of plant-based protein

Sheep, valued for meat, milk, and wool

Goats, adapted for variable terrain and climate

Cattle, later used for plowing and transport

The combination of plant cultivation and animal domestication allowed communities to adopt mixed farming systems, supporting settled life and early urbanization.

Indus River Valley: A Hearth Shaped by Riverine Environments

The Indus River Valley, located in present-day Pakistan and northwest India, represents another significant hearth of domestication. Its reliable river flooding cycles created fertile soils ideal for agricultural development. As settlements expanded, agricultural practices became more specialized and sophisticated.

Domesticated Species of the Indus Region

Agricultural innovations here were closely linked to the monsoon climate and annual flooding cycle.

Wheat and barley, diffusing partly from Southwest Asia

Cattle, particularly the zebu, a heat‐tolerant breed

Sesame, used for oil production

Cotton, one of the earliest fiber crops in the world

These domesticated species supported dense populations and contributed to the rise of planned urban centers such as Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa.

Southeast Asia: A Hearth of Root Crops and Maritime Diffusion

Southeast Asia’s tropical climate and biodiversity made it an important hearth for domestication, especially for root and tree crops suited to warm, humid environments. The region’s island geography also shaped agricultural diffusion, as early seafaring cultures transported crops across oceans.

Key Domesticated Plants and Animals

This hearth produced crops that are now staples for billions of people.

Rice, one of the world’s most important cereals, requiring flooded fields

Taro and yam, carbohydrate-rich root crops

Bananas, which spread widely through oceanic migration

Chickens, domesticated early and later spread across Asia and beyond

Maritime networks helped distribute these species into East Asia, South Asia, the Pacific Islands, and eventually Africa.

Central America: A Hearth of Maize and Indigenous Innovation

Central America, especially the region encompassing southern Mexico and northern Central America, served as a major hearth for the domestication of uniquely American crops. Indigenous groups developed complex agricultural techniques suited to diverse environments—from highland plateaus to tropical lowlands.

Domesticated Species from Central America

The region’s contributions profoundly shaped diets across the Americas and later the world.

Maize, a genetically modified grass species and one of the most influential crops in human history

Beans, complementing maize nutritionally through amino acid balance

Squash, providing dietary variety and early storage capacity

Turkeys, domesticated for meat and ceremonial uses

These crops formed the core of the Mesoamerican agricultural triad—maize, beans, and squash—which supported dense urban civilizations such as the Maya and Aztec.

Agricultural Hearths and Global Diffusion

The development of these domestication hearths reshaped human societies by providing stable food sources, enabling labor specialization, and laying foundations for early states. Over time, diffusion—through migration, trade routes, and cultural exchange—spread crops and livestock far beyond their origins, producing the diverse agricultural systems seen across the world today.

FAQ

Archaeologists look for physical changes in plant seeds or animal bones that differ from wild varieties, such as larger seed size or reduced horn shape.

They also examine settlement sites for tools, storage pits, controlled breeding patterns, and evidence of human management such as penned enclosures or irrigation features.

Different regions had unique combinations of climate, wild species, and human cultural practices that made domestication advantageous.

Independent invention occurred because communities faced similar challenges of food security and environmental variability, prompting innovation in multiple locations.

Foragers gradually intensified the harvesting of certain wild species, learning seasonal patterns and experimenting with planting.

This led to semi-sedentary lifestyles in some areas, where people returned to the same resource-rich locations each year, eventually creating conditions for cultivation.

Sheep and goats naturally inhabited the foothills and grasslands of Southwest Asia, making them accessible to human communities.

Their social behaviour, manageable size, and diet made them highly suitable for early domestication compared with wildlife found in other regions.

Surpluses from early agriculture supported larger communities, enabling the movement of people who carried domesticated species with them.

Cultural exchanges occurred through migration, intermarriage, and small-scale trade, spreading farming knowledge long before structured trade networks emerged.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Identify two early agricultural hearths where domestication of plants or animals first occurred, and briefly describe one crop or animal associated with each region.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

1 mark for each correctly identified hearth (up to 2 marks).

Acceptable answers include: the Fertile Crescent, the Indus River Valley, Southeast Asia, Central America.1 mark for describing one accurate crop or animal linked to one of the named hearths.

Examples:Fertile Crescent: wheat, barley, sheep, goats

Indus River Valley: zebu cattle, wheat, barley, cotton

Southeast Asia: rice, taro, yam, bananas, chickens

Central America: maize, beans, squash, turkeys

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Explain how the physical environments of two different agricultural hearths influenced the types of plants or animals that were domesticated there. Use specific examples to support your answer.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Award marks as follows:

1–2 marks: Identifies two hearths with basic or partial explanation of environmental influence.

3–4 marks: Provides clear explanation of how physical conditions (such as climate, soils, flooding regime, or biodiversity) shaped domestication choices in each hearth, with at least one accurate example for each region.

5–6 marks: Gives well-developed analysis comparing how different environmental factors in each hearth produced different domesticated species; uses precise examples of crops or animals; shows geographical understanding of environmental constraints and opportunities.

Indicative content may include:

Fertile Crescent: Mediterranean climate, wild stands of wheat and barley, grasslands suitable for herd animals (sheep, goats).

Indus River Valley: fertile alluvial soils and predictable river flooding supporting wheat, barley, and early cotton.

Southeast Asia: humid tropical climate supporting rice, taro, bananas; abundant forests enabling early chicken domestication.

Central America: diverse microclimates enabling maize, beans, and squash cultivation.