AP Syllabus focus:

‘Complex commodity chains connect agricultural production with processing, distribution, and consumption.’

Commodity chains explain how agricultural goods move from farms to consumers through linked stages of production, processing, transportation, and distribution, shaping economic relationships and global food systems.

Commodity Chains in Agricultural Geography

Commodity chains describe the sequential network of activities required to produce, transform, transport, and sell agricultural products.

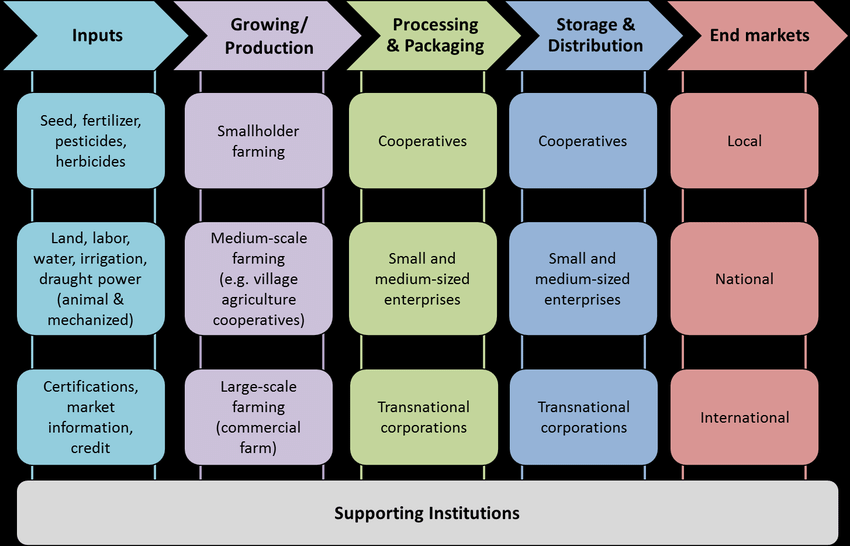

This diagram illustrates an agri-food value chain, moving from agricultural production through processing to later stages in the food system. Each box represents a key group of actors, such as farmers or food-processing companies, who add value at their stage in the chain. The figure includes some extra detail on supporting institutions, which can be mentioned as context but is not required knowledge for the AP Human Geography syllabus. Source.

These chains reveal how food systems depend on connections among farmers, agribusiness firms, processors, distributors, retailers, and consumers. They highlight the spatial, economic, and social relationships embedded within global and regional agriculture.

When geographers analyze a commodity chain, they examine not only the physical movement of goods but also the power dynamics, profit distribution, environmental impacts, and labor structures that shape each link. Understanding commodity chains helps explain why certain regions specialize in specific crops, how multinational corporations influence global markets, and why consumers have year-round access to diverse foods.

Key Components of Commodity Chains

Primary Production

This stage begins with producers, who supply the raw agricultural commodities.

Farmers grow crops or raise livestock.

Production reflects climate, land availability, technology, labor inputs, and capital, all of which vary across regions.

The organization of production may range from smallholder farms to large agribusiness operations.

Agricultural producers depend on access to inputs such as seeds, fertilizers, and machinery, all of which can place them within broader input-supplier chains.

Processing and Value Addition

Processing transforms raw agricultural goods into forms suitable for transport, sale, or consumption.

This value chain diagram shows how different stages of production and logistics combine to add value to a product before it reaches consumers. Although designed for a generic firm, it mirrors agricultural commodity chains where goods move from inbound logistics and operations through outbound logistics and marketing. The additional support activities at the top provide helpful context but are not specifically required by the AP Human Geography syllabus. Source.

Updating or altering a product raises its value-added characteristics, often increasing profit potential.

Examples include milling wheat into flour, fermenting cocoa into chocolate liquor, or cutting and packaging meat.

Many of these activities occur in specialized facilities operated by corporations that can use scale and technology to expand efficiency.

Value-added processing: The transformation of raw agricultural goods into products with higher economic value through cleaning, packaging, or manufacturing.

Processing concentrates economic power because firms operating at this stage often influence commodity prices and contract terms for farmers. These relationships help shape who benefits financially within the chain.

Distribution and Transportation

Distribution links geographically separated stages of the commodity chain.

Transportation modes may include trucking, rail, shipping, and air.

Infrastructure such as ports, highways, and refrigerated storage supports the movement of perishable goods.

Costs increase with distance, handling, and the need for preservation technologies.

Distribution often involves complex logistics designed to minimize delays and maintain product quality.

Retail and Consumption

The final stages connect products with consumers through grocery stores, restaurants, and food markets.

Retailers shape commodity chains by influencing what products are stocked, promoted, and priced.

Consumers contribute to demand patterns that determine which agricultural goods become commercially viable.

Consumer preferences—such as rising demand for organic, fair-trade, or locally sourced foods—can restructure entire commodity chains.

Types of Agricultural Commodity Chains

Traditional or Short Commodity Chains

These chains have fewer intermediaries and shorter distances between producers and consumers.

Often found in local or regional markets.

Emphasize freshness, reduced transportation, and stronger producer–consumer relationships.

Common in farmers’ markets, community-supported agriculture (CSA), and local food systems.

Shorter chains may increase farmers’ share of profit and reduce environmental costs associated with transportation.

Industrial or Global Commodity Chains

Global commodity chains involve multiple stages across several countries.

Typically controlled by large multinational corporations.

Rely on standardized processes, global logistics, and international trade agreements.

Allow year-round availability of foods such as bananas, coffee, and beef.

Global chains can create economic opportunities but may also reinforce unequal power relationships.

Global commodity chain: A geographically dispersed network of production and distribution coordinated across multiple countries by firms and intermediaries.

Because global chains involve many actors, they often depend on economies of scale, enabling cost reductions through large-volume production.

Power Dynamics Within Commodity Chains

Commodity chains reveal how economic power is unevenly distributed.

Farmers may receive relatively low prices because processors or retailers set contract terms.

Large agribusiness firms often coordinate several chain segments, increasing market control.

Certification groups, trade organizations, and government regulations shape standards for labor, safety, or environmental practices.

Power concentration can influence which regions specialize in high-value crops and how much profit stays within local communities.

Sustainability and Equity Concerns

Commodity chains raise important debates about human and environmental impacts.

Long-distance transportation increases carbon emissions.

Processing facilities may generate pollution or create labor challenges.

Unequal distribution of profits can perpetuate rural poverty.

Consumer demand for ethically produced goods encourages certification systems such as fair trade.

Geographers evaluate how these chains can be redesigned to support sustainability, improve working conditions, and promote more equitable global food systems.

Why Commodity Chains Matter for AP Human Geography

Understanding commodity chains helps students analyze how agricultural systems operate at multiple scales. The movement of goods from producers to consumers illustrates how interconnected the global food system has become and emphasizes the role of space, economics, and human decision-making in shaping agricultural landscapes.

FAQ

Perishable goods such as fresh fruit, milk, or leafy vegetables require rapid movement through the commodity chain. Cold storage, refrigerated transport, and tight scheduling are essential, making these chains more costly and technologically demanding.

Non-perishable goods like grain or dried pulses move more slowly and can be stored for long periods. Their chains involve larger inventories, fewer time-sensitive steps, and generally lower transportation costs.

Perishable chains therefore tend to have fewer intermediaries and stricter coordination, while non-perishable chains can operate at larger scales with more flexible logistics.

Intermediaries act as connectors between farmers, processors, distributors, and retailers. They may purchase products directly from producers, consolidate shipments, or negotiate contracts.

Their influence can affect:

• Farm-gate prices

• Quality standards

• Access to distant markets

• The pace at which goods move through the chain

While intermediaries can expand market access for small producers, they may also capture a significant share of profits, reinforcing unequal power dynamics.

Certification systems such as organic or fair-trade introduce additional requirements for producers, including standards for environmental practices, labour conditions, or chemical use.

These schemes can reshape commodity chains by:

• Adding monitoring and auditing organisations

• Increasing traceability through each stage

• Establishing premium markets where certified goods command higher prices

Certification often shifts power towards retailers and certifying bodies, who determine market access and compliance criteria.

Multinational firms often control several chain stages, from processing to global distribution. Their capital resources enable investment in technology, large-scale transport networks, and global marketing.

This dominance emerges because these firms can:

• Negotiate favourable supply contracts

• Standardise production to meet international demand

• Reduce costs through economies of scale

As a result, small producers may become dependent on terms set by larger firms, reducing their influence within the chain.

Shifts in consumer preferences—such as demand for plant-based products, ethically sourced goods, or reduced packaging—directly influence how firms source, process, and distribute agricultural commodities.

Retailers respond by altering:

• Contract requirements

• Product sourcing locations

• Packaging and distribution strategies

These adjustments ripple backwards through the chain, prompting producers and processors to adopt new practices, sometimes changing entire production systems or regional specialisations.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain how value-added processing functions as part of an agricultural commodity chain.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Award up to 3 marks for the following points:

(1 mark) Identifies that value-added processing transforms raw agricultural goods into products with higher economic value.

(1 mark) Explains that this stage adds economic value through actions such as cleaning, packaging, or manufacturing.

(1 mark) Links value-added processing to the wider commodity chain by noting that it prepares goods for transport, distribution, or sale.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Using examples, analyse how global commodity chains create uneven power relationships between different actors from agricultural producers to retailers.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Award marks for the following elements:

(1 mark) Identifies that global commodity chains involve multiple countries and actors.

(1 mark) States that power is unevenly distributed across these actors.

(1–2 marks) Provides examples (e.g., multinational processing firms, supermarket retailers) and explains how they influence prices, contracts, or production terms.

(1–2 marks) Analyses how producers, especially smallholders, may receive lower profits due to limited bargaining power, while retailers or processors capture a larger share of value.

(1 mark) Links the analysis to a consequence such as reduced local economic benefits, market dependency, or consumer-driven restructuring of chains.