AP Syllabus focus:

‘Trade is based on complementarity and comparative advantage—places specialize in goods they can produce more efficiently.’

Countries trade because they gain mutual benefits from exchanging goods produced more efficiently in different locations, shaping global economic patterns and encouraging geographic specialization based on resources, skills, and demand.

Why Trade Happens

Understanding Complementarity in Global Trade

Complementarity refers to the fit between what one place produces and what another place demands, making exchange beneficial.

Complementarity: When one region’s supply of a good matches another region’s demand, creating conditions that encourage trade between them.

Complementarity underpins the spatial logic of trade relationships and explains why global economic flows often connect regions with contrasting resource endowments or consumption needs. Trade emerges when two places are more useful to each other together than they are apart.

Key drivers of complementarity include:

Differing natural resources, such as mineral-rich countries exporting raw materials to manufacturing economies.

Contrasting climates, enabling exchanges like tropical agricultural products for temperate-zone grains.

Specialized labor forces, where one region has workers skilled in tasks that another lacks.

Market demand, as advanced economies may seek goods not produced domestically.

Complementarity reflects the spatial distribution of economic strengths and needs, helping explain persistent trade patterns between global regions.

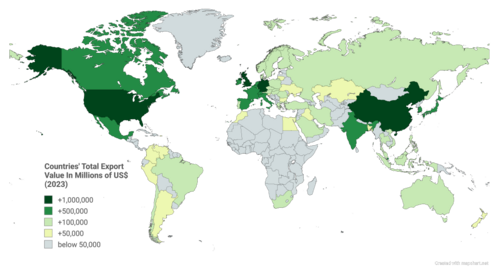

World map showing total exports by country, with darker shading indicating higher export values. The map highlights how a relatively small number of countries account for a large share of global trade, reflecting their ability to produce certain goods and services more competitively. The specific year (2023) and exact export values are beyond the AP Human Geography syllabus but offer an up-to-date empirical example of trade concentration. Source.

Comparative Advantage and Specialization

Trade also results from comparative advantage, a foundational idea in economics and human geography. Comparative advantage explains why places specialize in producing goods they can make at lower opportunity cost than others, even if they are not the most efficient producers overall.

Comparative Advantage: The economic principle that regions should specialize in producing goods for which they have the lowest opportunity cost, enabling more efficient global production.

This concept matters for understanding the geography of production. A country may lack an absolute advantage—producing a good more efficiently in total terms—but still benefit from specializing in the products it gives up the least to produce.

After regions specialize according to comparative advantage, trade allows them to obtain other goods more cheaply than if they attempted to produce everything domestically.

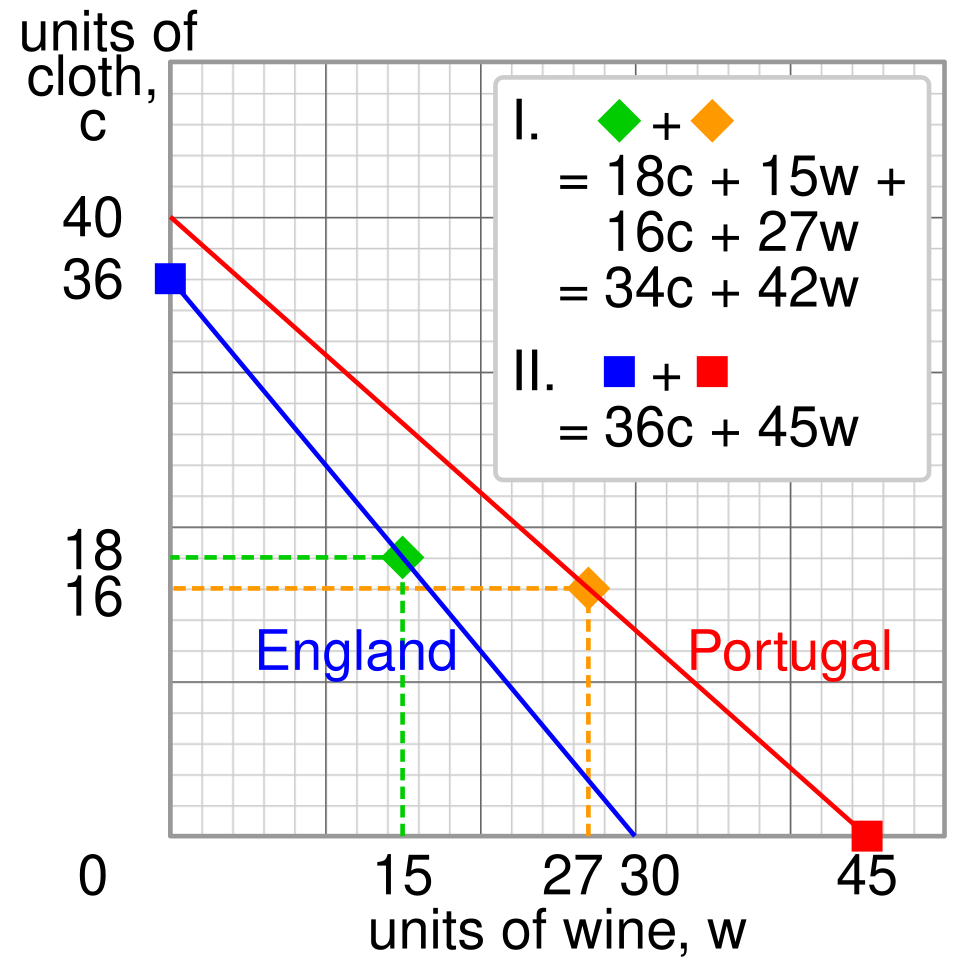

Graph illustrating Ricardo’s example of comparative advantage, where each country specializes in the good it produces relatively more efficiently and then trades. The diagram compares a case with no specialization to a case with specialization and shows that total combined output is higher when each country focuses on its comparative advantage. The extra detail about specific labor hours and the cloth–wine example goes beyond the AP Human Geography syllabus but visually clarifies the gains from trade. Source.

Factors Shaping Comparative Advantage

Comparative advantage is influenced by several geographic and economic conditions:

Resource endowments: Access to minerals, fertile soil, freshwater, or energy sources can give a region an advantage in resource-dependent industries.

Climate and environmental conditions: Weather patterns determine agricultural suitability and thus trade in food products.

Labor supply and skills: Regions with skilled engineers may excel in technology manufacturing, while those with large unskilled labor pools may specialize in low-cost assembly work.

Capital availability: Places with investment capital can develop industries that others cannot.

Technological capability: Innovations in production methods create competitive advantages for certain regions.

These factors vary spatially, producing the differentiated economic landscapes central to AP Human Geography.

Spatial Interactions Resulting From Trade

Complementarity and comparative advantage create predictable spatial patterns in global economic interactions:

Flows of raw materials from resource-rich periphery regions to industrial core regions.

Flows of manufactured goods from industrial regions to consumer markets worldwide.

Development of trade routes such as shipping lanes, rail corridors, and port cities that optimize movement.

Growth of global supply chains, where production processes stretch across multiple locations to exploit localized advantages.

Trade also encourages regions to invest in infrastructure—such as ports or logistics hubs—that reinforces their role in global networks.

How Trade Structures Regional Development

The principles behind trade influence how regions develop economically and spatially:

Regions with strong comparative advantages may industrialize more rapidly.

Areas with valuable export commodities often become integrated into global markets earlier.

Dependence on a limited range of exports can create vulnerabilities, especially in periphery regions.

Core regions often benefit disproportionately from trade due to advanced infrastructure, capital, and technological leadership.

These uneven trade relationships help explain broader patterns of global economic inequality highlighted elsewhere in the AP curriculum.

Complementarity and Comparative Advantage in Today’s World Economy

In contemporary globalization, complementarity and comparative advantage shape everything from agricultural trade to high-tech production networks. For example:

Countries with abundant sunlight and land may specialize in solar energy generation or large-scale agriculture.

Nations with advanced research sectors specialize in pharmaceuticals, aerospace, or data services.

Economies with low labor costs attract manufacturing and assembly activities.

These geographic specializations support international trade flows that connect regions with distinct economic roles.

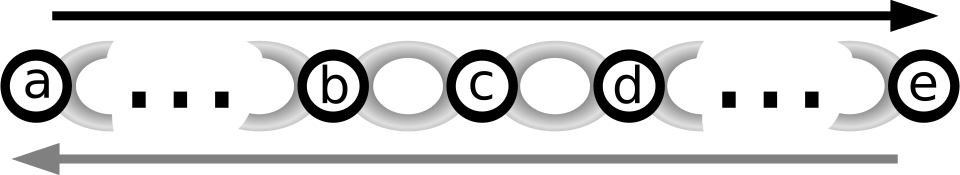

Simplified diagram of a supply chain, with stages labeled from initial supplier through manufacturer and customer to the final customer. The black arrow shows the main flow of materials, while the gray arrow represents information and return flows. The detailed stage labels extend slightly beyond the AP Human Geography syllabus but clearly illustrate how different locations specialize in different steps and are linked through trade. Source.

FAQ

Complementarity requires both a matching surplus and a matching need, whereas simple demand may exist without a corresponding surplus in another location.

When complementarity exists, the exchange is mutually beneficial because each side provides something the other lacks. Without it, trade may still occur, but it is often more costly or relies on imports from distant or less efficient suppliers.

Yes. Complementarity is dynamic and shifts as countries industrialise, change consumption patterns, or develop new technologies.

For example, a country that once imported manufactured goods may develop its own industrial base, reducing the previous complementarity.

Similarly, climate change or resource depletion can alter what regions can produce, reshaping trade relationships.

Comparative advantage can erode when:

labour costs rise relative to competitors

technology becomes outdated

key resources become scarce

political instability discourages investment

environmental regulations increase production costs

Shifts in global consumer demand can also undermine a region’s specialisation, especially if it relies heavily on a narrow export base.

Full specialisation can increase vulnerability if global demand fluctuates or if a country becomes overly dependent on imports for essentials.

Governments sometimes maintain limited domestic production of strategic goods—such as food or energy—to reduce risk.

Cultural preferences and national identity can also motivate continued production of certain goods despite comparative disadvantage.

Comparative advantage only results in trade if the cost of transporting goods does not outweigh the efficiency gains from specialisation.

High transport costs can make it unprofitable to trade bulky, low-value items even if one region produces them more efficiently.

Improvements in infrastructure, shipping technology, or trade corridors can turn a theoretical comparative advantage into a practical one by reducing the friction of distance.

Practice Questions

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Discuss how comparative advantage influences global patterns of production and trade. In your answer, refer to both economic factors and spatial variation.

(6 marks)

Mark scheme:

1 mark for stating that comparative advantage refers to production at lower opportunity cost.

1 mark for explaining that regions specialise in goods they can produce most efficiently relative to alternatives.

1 mark for linking specialisation to increased total global output and gains from trade.

1 mark for describing at least one economic factor influencing comparative advantage (e.g., labour skills, capital availability, technology).

1 mark for describing at least one spatial factor (e.g., climate, resource endowment, location).

1 mark for showing how these combined factors produce uneven global patterns of production and trade (e.g., manufacturing clusters, agricultural exporters, resource-based economies).

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain the concept of complementarity in global trade. Use one real or plausible example to support your answer.

(3 marks)

Mark scheme:

1 mark for defining complementarity as when one region’s supply matches another region’s demand.

1 mark for explaining that this creates mutually beneficial conditions for trade.

1 mark for providing a relevant example (e.g., a country with surplus oil exporting to a country with high energy demand; a tropical state exporting bananas to a temperate country).