AQA Specification focus:

‘Economics as a social science; similarities to and differences in methodology from natural and other sciences; students should understand how thinking as an economist may differ from other forms of scientific enquiry.’

Economics is a social science that studies how societies allocate scarce resources to meet needs and wants, combining empirical investigation with theoretical models to explain and predict economic behaviour.

Economics as a Social Science

Economics investigates human behaviour and decision-making in the context of scarcity, choice, and resource allocation. As a social science, it uses systematic methods to analyse how individuals, firms, and governments make economic choices, while recognising that human behaviour is influenced by social, cultural, and political factors.

Social science: A field of study that examines human society and social relationships using systematic and evidence-based methods.

Economics, like other social sciences (e.g., sociology, political science), aims to understand and explain patterns of human behaviour, but focuses specifically on production, distribution, and consumption of goods and services.

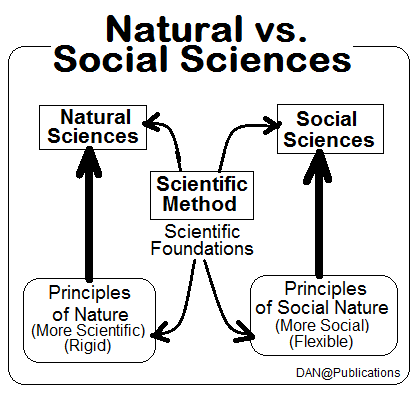

This diagram contrasts natural sciences, which study physical and biological phenomena, with social sciences, which examine human behaviour and societal structures. It highlights methodological differences, such as controlled experiments in natural sciences versus observational studies in social sciences. Source

Similarities with Natural Sciences

Economics shares important methodological features with natural sciences such as physics or biology:

Use of models and theories to explain observed phenomena.

Hypothesis formulation to predict outcomes based on assumptions.

Data collection and statistical analysis to test theories against real-world evidence.

Empirical validation — theories are supported when evidence consistently matches predictions.

Systematic observation to ensure research is replicable and verifiable.

These shared features mean that economics values objectivity, logical reasoning, and empirical evidence, just as in natural sciences.

Differences from Natural Sciences

While economics borrows scientific techniques, it faces unique challenges that distinguish it from natural sciences:

Human behaviour is complex and variable: Unlike physical particles, people adapt their behaviour in unpredictable ways, making universal laws harder to establish.

Controlled experiments are limited: Ethical and practical constraints mean economists often rely on observational data rather than laboratory experiments.

Influence of value judgements: Social, moral, and political beliefs can influence both the interpretation of data and the choice of research questions.

Multiple interacting variables: Economic outcomes are shaped by numerous factors, often making it difficult to isolate causes.

Value judgement: An assessment based on personal beliefs or opinions rather than objective facts.

Because of these differences, economics often produces theories that are probabilistic (predicting likely outcomes) rather than deterministic (predicting exact results).

Methodology in Economics

Economists follow a structured approach to enquiry:

Identify an economic problem or question — often arising from real-world events or policy debates.

Develop a theoretical model — simplify reality by focusing on key variables and assuming other factors remain constant (ceteris paribus).

Formulate hypotheses — predictions about how changes in one variable will affect others.

Collect data — from surveys, government statistics, experiments, or case studies.

Test hypotheses — using statistical and econometric methods to assess accuracy.

Draw conclusions and refine theory — adapt models in light of evidence.

Ceteris paribus: A Latin phrase meaning "all other things being equal", used to isolate the effect of one variable.

The Role of Models in Economics

Economic models are simplified representations of reality that help economists understand relationships between variables. They strip away unnecessary complexity to focus on core mechanisms, often using diagrams or equations.

Normative simplicity: Models assume away certain real-world details to allow clearer analysis.

Predictive power: Models can forecast the effects of changes in policy or economic conditions.

Testability: Predictions from models can be compared with actual data.

However, models are only as good as their assumptions, and their predictive accuracy can be limited if real-world conditions differ significantly from those assumed.

Thinking Like an Economist

Thinking as an economist involves a distinct perspective:

Opportunity cost awareness: Recognising that every choice involves trade-offs.

Marginal analysis: Assessing the additional benefits and costs of a decision.

Evidence-based reasoning: Using data and logical argument to support conclusions.

Balancing theory and reality: Applying abstract models to practical contexts while acknowledging limitations.

Policy evaluation: Judging economic policies on efficiency, equity, and feasibility.

Opportunity cost: The next best alternative foregone when a choice is made.

The Interplay Between Theory and Evidence

Economics relies on a feedback loop between theory and empirical evidence:

Theory informs data collection — hypotheses suggest what to measure.

Data tests theory — evidence confirms, refines, or refutes theoretical predictions.

Policy implications — findings guide government and business decisions.

This iterative process is similar to that in natural sciences, but economics must account for human behaviour’s unpredictability, meaning results can vary across time and context.

The Role of Assumptions

All economic analysis is based on assumptions that simplify the complexity of real life:

Rational behaviour: Assuming individuals act to maximise utility.

Perfect information: Assuming all market participants have complete knowledge.

Ceteris paribus: Holding other variables constant to isolate effects.

While these assumptions are rarely true in full, they provide a starting point for analysis. Economists adjust models when assumptions are too unrealistic for the problem at hand.

Limitations of the Economic Method

Key constraints in applying economic methodology include:

Dynamic and evolving behaviour: Economic agents learn and adapt over time.

Cultural and institutional differences: Policies that work in one country may fail in another.

Measurement issues: Economic variables (e.g., quality of life) can be hard to quantify.

Ethical considerations: Some policies or experiments may be socially unacceptable despite potential benefits.

Economics and Other Sciences

Economics also overlaps with:

Psychology — behavioural economics studies how cognitive biases affect decisions.

Environmental science — exploring the allocation of natural resources.

Political science — examining how political structures affect economic policy.

This interdisciplinarity enriches economic analysis but also introduces more variables, further distinguishing it from the relatively controlled systems in natural sciences.

FAQ

Economics is classified as a social science because it studies human decision-making, behaviour, and interactions in the context of scarce resources.

While natural sciences focus on physical and biological phenomena governed by consistent laws, economics deals with human actions, which are influenced by values, cultures, and changing circumstances.

Yes, but with significant limitations. Field experiments and laboratory-based economic experiments do exist, often in behavioural economics.

However, large-scale controlled experiments are rare because:

Human behaviour is unpredictable and context-dependent.

Ethical and practical constraints limit the manipulation of economic conditions.

Real-world economies are influenced by too many variables to fully control.

Economic models often use simplifying assumptions, such as rational behaviour and ceteris paribus, to make analysis manageable.

Unpredictability means:

Models produce probabilistic, not deterministic, predictions.

They may require constant adjustment as social, political, and cultural contexts change.

External shocks (e.g., crises) can render models temporarily less reliable.

Value judgements influence what topics are studied, how questions are framed, and how results are interpreted.

They affect:

Policy recommendations, which may reflect moral or political priorities.

Choice of indicators (e.g., GDP growth vs. income equality).

Public debates, where data may be presented selectively to support a viewpoint.

Ceteris paribus allows economists to isolate the effect of one variable by assuming other factors remain unchanged.

Limitations include:

In real economies, variables rarely remain constant.

Interdependence of factors means ignoring one can distort analysis.

It simplifies analysis for learning and theory, but conclusions must be applied with caution in real-world contexts.

Practice Questions

Define the term "social science" in the context of economics. (2 marks)

1 mark for identifying that a social science studies human behaviour or society.

1 mark for stating that it uses systematic and evidence-based methods.

Explain two key differences between the methodology used in economics and that used in natural sciences. (6 marks)

Up to 3 marks for each difference explained (2 differences required):

1 mark for identifying the difference (e.g., human behaviour variability vs predictable physical laws).

1 mark for describing how this affects research methods (e.g., difficulty in controlling experiments in economics).

1 mark for developing the point with relevant elaboration or example (e.g., economists relying on observational data rather than laboratory experiments).