AQA Specification focus:

‘The causes and effects of poverty.’

Poverty emerges from interconnected structural and individual factors. Understanding these causes helps explain persistent deprivation and informs debates on policy responses within economic and social contexts.

Structural Causes of Poverty

Structural factors are deep-rooted, systemic conditions in an economy and society that constrain opportunities for certain groups. They are often outside individual control.

Labour Market Inequalities

Unemployment and underemployment reduce household income, limiting access to basic goods and services.

Low-wage employment traps individuals in a cycle of working poverty.

Skill mismatches occur when workers’ skills do not align with labour market demand.

Working Poverty: A situation where individuals are employed but still cannot achieve a minimum standard of living due to low wages or insecure work.

Capital and Wealth Distribution

Ownership of capital assets such as property, financial investments, and businesses creates long-term income streams.

Concentrated wealth leads to persistent inequality and exclusion of those without access to capital.

Institutional and Policy Structures

Tax systems that are regressive, relying heavily on indirect taxes, place disproportionate burdens on low-income households.

Education systems that underfund disadvantaged areas reduce social mobility.

Healthcare inequalities hinder productivity and earning potential.

Regional Disparities

Uneven economic development creates areas with fewer job opportunities and lower wages.

Structural poverty is reinforced by poor infrastructure, limited investment, and restricted public services in deprived regions.

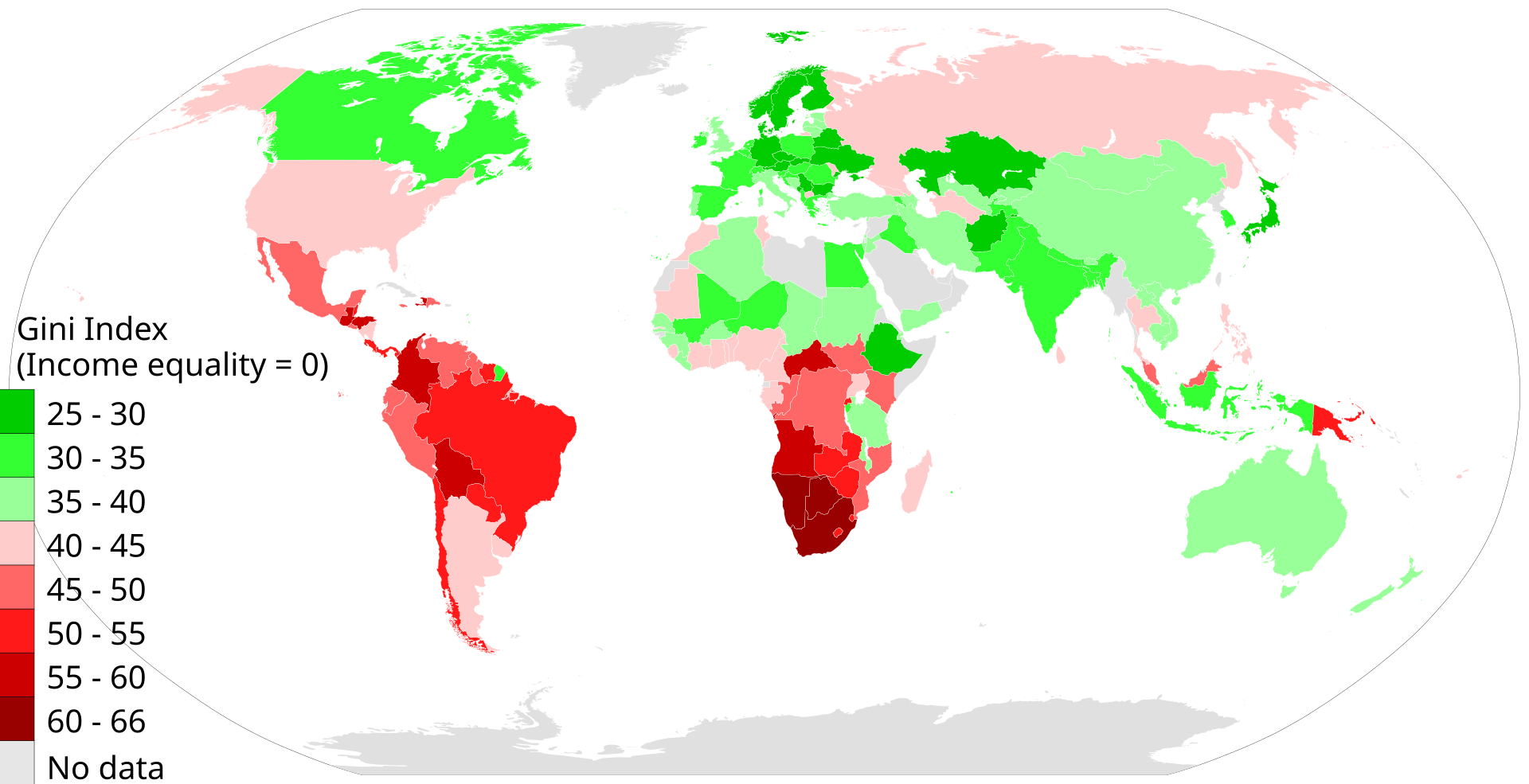

This map illustrates the Gini Index by country, indicating income inequality levels worldwide. Countries shaded in red exhibit higher inequality, reflecting structural factors like regional disparities and institutional policies that contribute to poverty. Note: The map's data is from 2014, and some individual data points may be more than 10 years old. Source

Individual Causes of Poverty

Individual factors refer to characteristics and choices that may influence poverty risk, though they often interact with wider structural constraints.

Education and Skills

Low levels of educational attainment reduce access to higher-paying jobs.

Lack of vocational or technical skills can confine individuals to insecure work.

Human Capital: The stock of skills, knowledge, and experience possessed by an individual that determines their productivity and earning potential.

Health and Disability

Chronic illness or disability limits work capacity and increases reliance on state support.

Poor health reduces productivity, discourages employers, and raises household expenditure.

Family and Household Structure

Single-parent households often face a higher risk of poverty due to limited income earners and higher childcare costs.

Larger families may experience strain on resources, especially when wages are low.

Behavioural and Social Factors

Addiction and substance abuse can diminish employability and deplete household resources.

Intergenerational poverty persists when limited aspirations and opportunities are transmitted across generations.

Interactions Between Structural and Individual Factors

Poverty rarely results from a single cause; it emerges from the interplay of systemic and personal factors. For example:

A poorly educated individual (individual factor) is more likely to face unemployment in a region of declining industries (structural factor).

Ill health may reduce earning capacity, while inadequate healthcare systems fail to provide effective treatment, reinforcing long-term deprivation.

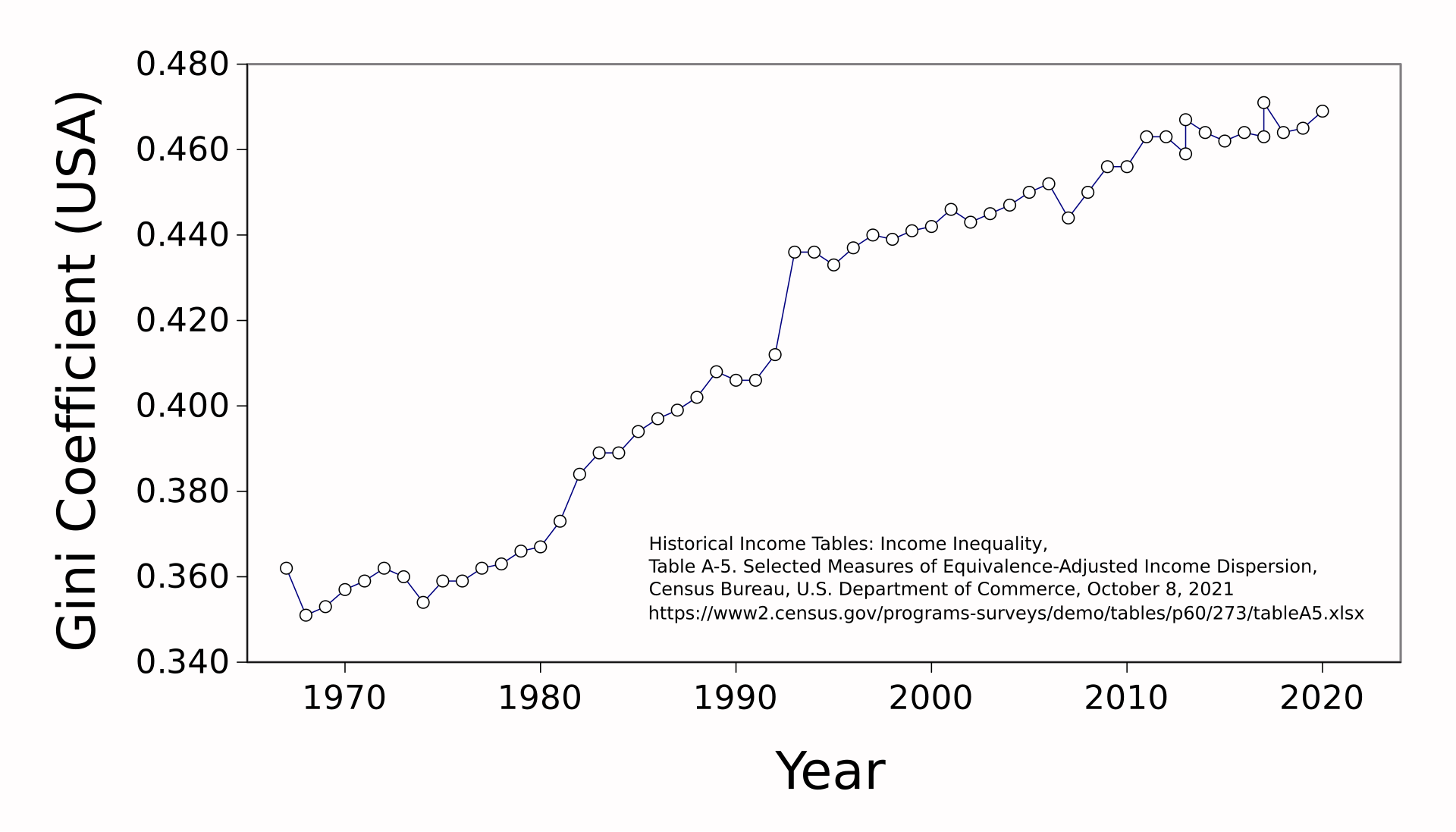

This line chart displays the Gini Coefficient for the United States from 1967 to 2020, highlighting trends in income inequality. The data reflects how individual factors, such as education and employment, intersect with broader economic conditions to influence poverty levels. Note: The chart's data is sourced from the U.S. Census Bureau. Source

Effects of Poverty

According to the specification, students should understand not only the causes but also the effects of poverty. These effects operate at both the household level and across the wider economy.

Household-Level Effects

Material deprivation: Inability to afford necessities such as adequate housing, food, and heating.

Educational disadvantages: Children in poverty often experience lower attainment due to poor resources and limited opportunities.

Health outcomes: Poverty is linked to shorter life expectancy, chronic illness, and limited access to healthcare.

Macroeconomic Effects

Reduced productivity: A workforce suffering from poor health and low education weakens overall economic growth.

Higher welfare costs: Governments must allocate more resources to social security programmes.

Social instability: High poverty levels can fuel crime, unrest, and political tension.

Structural vs Individual Explanations

Economists and policymakers debate the relative importance of structural versus individual causes:

Structural explanations emphasise systemic reform, such as progressive taxation, investment in education, and labour market regulation.

Individual explanations focus on improving skills, behaviour, and personal responsibility.

Poverty Trap: A self-reinforcing situation where low income leads to limited opportunities, which in turn perpetuate low income across generations.

While both sets of factors are valid, structural conditions often shape and constrain individual choices, meaning effective anti-poverty policy must address both dimensions simultaneously.

FAQ

Cyclical unemployment occurs during downturns in the business cycle, when reduced demand lowers employment across industries. This can temporarily increase poverty.

Structural unemployment is long-term and results from fundamental changes in the economy, such as automation or the decline of specific industries. This has a deeper link to persistent poverty, as affected workers often lack the skills to move into new sectors.

Certain UK regions, such as parts of the North East and former industrial areas, have experienced long-term economic decline.

Fewer employment opportunities

Lower average wages

Less investment in public infrastructure

These disparities reinforce structural poverty by limiting upward mobility for households within disadvantaged regions.

Poor health can cause poverty by reducing an individual’s ability to work, increasing reliance on benefits, and raising household medical expenses.

Poverty can also worsen health outcomes through inadequate nutrition, substandard housing, and limited access to healthcare. This creates a feedback loop where ill health and poverty reinforce one another.

Single-parent households often rely on a single income stream, which can be low or insecure.

Additional costs include childcare, which can consume a large share of earnings. Without strong support systems, such households are more vulnerable to falling below the poverty line.

Intergenerational poverty arises when disadvantages are passed from parents to children.

Low parental income restricts access to quality education and resources.

Children grow up with limited aspirations or opportunities.

As adults, they may replicate the same cycle of low skills and low income.

This self-reinforcing cycle makes poverty persist across generations without targeted intervention.

Practice Questions

Explain the difference between structural and individual causes of poverty. (3 marks)

1 mark for identifying structural causes as systemic/economic factors outside individual control (e.g. labour market conditions, tax systems, regional disparities).

1 mark for identifying individual causes as personal/household factors (e.g. education, health, family structure).

1 mark for clear distinction made between the two (e.g. structural relates to wider economy and institutions, individual relates to personal characteristics/choices).

Discuss how structural and individual factors can interact to cause poverty in an economy. (6 marks)

1–2 marks: Identifies structural factors (e.g. unemployment, unequal education, regressive taxation) and individual factors (e.g. low skills, poor health, family structure).

1–2 marks: Explains interaction (e.g. a poorly educated individual more likely to face unemployment in a declining industry).

1–2 marks: Develops analysis of how the interaction reinforces poverty (e.g. health issues worsen when healthcare access is poor, limiting ability to work).

Level of response:

Basic (1–2 marks): General statements about causes of poverty.

Reasonable (3–4 marks): Some explanation of both structural and individual factors with limited link to interaction.

Strong (5–6 marks): Clear explanation of both categories, detailed example of interaction, and logical economic reasoning.