OCR Specification focus:

‘The decline of the Byzantine and the Sassanian Empires and the impact on the Arab world; the impact of plague and warfare’

The weakening of the Byzantine and Sassanian Empires in the sixth and seventh centuries transformed the balance of power in the Middle East, creating opportunities for the rise of Islam.

The Byzantine Empire in Decline

The Byzantine Empire, centred on Constantinople, had long been a dominant Mediterranean power. Yet by the early seventh century, it was strained politically, militarily, and economically.

Political Instability

Frequent palace coups, assassinations, and contested successions undermined central authority.

Provincial governors and generals often acted with semi-independence, weakening imperial cohesion.

Religious disputes, particularly concerning Monophysitism and the role of the Chalcedonian Church, divided populations in Syria and Egypt, reducing loyalty to Constantinople.

Economic Problems

Continuous taxation to fund wars placed a heavy burden on peasants and landowners.

Agricultural productivity declined in some regions due to over-farming and lack of investment.

Trade was disrupted by wars with Persia, depriving the empire of revenues from key Silk Road routes.

Military Strains

The Byzantine military was overstretched by:

Defending frontiers in the Balkans against Slavs and Avars.

Repelling Sassanian offensives in Mesopotamia and Syria.

Maintaining fleets in the Mediterranean.

This constant warfare drained resources and prevented long-term consolidation.

The Sassanian Empire in Decline

The Sassanian Empire, based in Persia, was Byzantium’s great eastern rival. It too faced terminal weaknesses by the early seventh century.

Political Weaknesses

A rigid monarchy concentrated power in the hands of the shah, but succession was often violent.

After the death of Khosrow II (628), the empire entered a period of instability with multiple rulers over a few years, destroying central authority.

Economic and Social Issues

Continuous mobilisation of manpower and resources for war exhausted the agrarian economy.

Heavy taxation fuelled resentment among the peasantry.

Nobility and landed elites became increasingly powerful, undermining the shah’s authority.

Military Exhaustion

The Sassanian army, though famed for its cataphracts (heavily armoured cavalry), was overstretched:

Decades of war against Byzantium left garrisons weak and supplies depleted.

Border tribes often resisted central control, draining resources through constant rebellion.

The Byzantine–Sassanian Wars

The two empires fought almost continuously in the sixth and early seventh centuries.

Key Features

Wars centred on contested regions: Mesopotamia, Armenia, and Syria.

Both sides won temporary victories, but neither could establish permanent dominance.

The final great war (602–628) under Emperor Heraclius and Khosrow II was devastating for both empires.

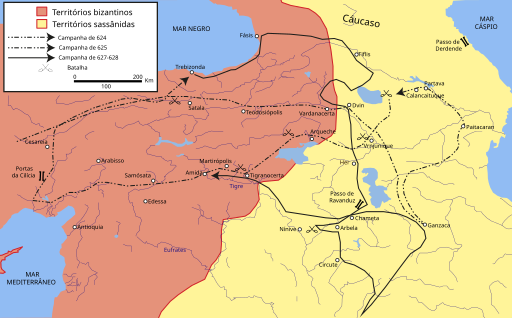

Map of the Byzantine–Sasanian campaigns (624–628) with labelled routes, key regions and theatres in Anatolia, the Caucasus, and Mesopotamia. It visualises Heraclius’ counter-offensives and the shifting front lines that left both powers fiscally and militarily depleted. Source

Impact of War

Cities such as Antioch and Ctesiphon suffered repeated sieges and sackings.

Agricultural lands were destroyed, causing famine and depopulation.

Exhaustion left both empires unable to resist new external threats.

The Impact of Plague

The Plague of Justinian (beginning in 541 CE) was a critical blow to both empires.

Plague of Justinian: A pandemic, likely bubonic plague, that struck the Mediterranean world from the mid-sixth century onwards, recurring in waves for two centuries.

Consequences

Vast population losses, particularly in cities such as Constantinople and Alexandria.

Reduced tax revenues as farmland was abandoned and labour shortages grew.

Decline in trade and military recruitment due to shrinking urban populations.

Plague combined with war to create a cycle of economic contraction and demographic decline.

The Arab World and the Empires’ Decline

The decline of the Byzantine and Sassanian empires had profound consequences for Arabia and the wider Middle East.

Weak Frontiers

Both empires relied on Arab buffer states, such as the Ghassanids (Byzantine clients) and Lakhmids (Sassanian clients), to police desert borders.

Map of the Ghassanid Kingdom in the Levant relative to Byzantine border corridors. This supports the point that imperial defence depended on allied Arab polities controlling approach routes. Source

Opportunities for Arab Tribes

The breakdown of imperial power allowed Arab tribes to expand influence across Syria, Mesopotamia, and the Levant.

Economic opportunities grew as traditional trade routes, once dominated by the empires, became more accessible to Arabs.

Religious and Political Openings

Populations disaffected by Byzantine religious orthodoxy (particularly Monophysite Christians in Syria and Egypt) were more open to alternative authorities.

In Persia, resentment of high taxation and political instability made locals more receptive to change.

The Stage for the Rise of Islam

The combination of plague, war, and political turmoil left both Byzantium and Persia vulnerable at the precise moment Islam was emerging in Arabia.

Byzantine and Sassanian military exhaustion created power vacuums in Syria, Iraq, and Egypt.

Arab tribes, newly united under Islamic leadership, were positioned to expand into these weakened territories.

The disillusionment of subject populations with imperial rule facilitated the relatively rapid success of Arab conquests.

Thus, the decline of the Byzantine and Sassanian Empires, alongside the impact of plague and warfare, reshaped the Middle East and opened the path for Islam’s expansion.

FAQ

Heraclius reorganised the empire’s finances by appealing to the Church for wealth to fund campaigns.

He adopted a more mobile style of warfare, conducting daring campaigns deep into Persian territory, including the Caucasus.

By 627, his forces defeated the Persians at Nineveh, forcing the withdrawal of Sassanian troops from occupied Byzantine lands.

Although temporarily successful, the effort left the empire exhausted and unable to resist new threats from Arabia.

Many populations in these regions adhered to Monophysite Christianity, which clashed with the official Chalcedonian doctrine enforced by Constantinople.

The imperial government’s attempts to impose orthodoxy created resentment and weakened loyalty among local elites and clergy.

When Arab forces later advanced, some local communities viewed them as preferable to Byzantine religious control, reducing resistance.

In what ways did the nobility contribute to the decline of the Sassanian Empire?

The Persian nobility held vast estates and increasingly resisted central authority, particularly during times of instability.

After Khosrow II’s death, rival noble factions promoted different claimants to the throne, accelerating political fragmentation.

Their desire to protect wealth and privileges often outweighed loyalty to the shah, undermining coordinated responses to crises.

This decentralisation weakened the empire at precisely the moment Arab expansion began.

The plague reduced available manpower, both in rural communities and in cities.

Fewer peasants meant a shrinking pool of potential conscripts.

Declining urban populations reduced the number of professional soldiers and sailors.

Economic strain limited the ability to hire mercenaries.

This shortage meant armies were under-strength and difficult to replace after defeats, weakening Byzantium’s resilience.

The Lakhmids, based in al-Hirah, acted as Sassanian allies guarding desert approaches to Mesopotamia.

In 602, Khosrow II abolished their kingdom, removing a vital protective layer.

Without the Lakhmids, Persia’s western frontier was exposed to raids by Arab tribes.

This strategic miscalculation left Mesopotamia more vulnerable just as internal instability worsened.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks)

Name one major factor that weakened the Byzantine Empire and one that weakened the Sassanian Empire in the early seventh century.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying a valid factor for Byzantium (e.g. “religious disputes such as Monophysitism,” “heavy taxation,” “military overstretch,” or “political instability”).

1 mark for identifying a valid factor for the Sassanians (e.g. “succession crises after Khosrow II,” “heavy taxation,” “exhaustion from continuous warfare,” or “noble elites undermining central power”).

(Maximum 2 marks)

Question 2 (6 marks)

Explain how the decline of the Byzantine and Sassanian Empires created opportunities for the expansion of Arab influence in the early seventh century.

Mark scheme:

1–2 marks: Limited explanation, may mention general weakness of empires without linking to Arab opportunities (e.g. “they were weak after wars”).

3–4 marks: Clear explanation of how specific weaknesses opened opportunities (e.g. “Byzantine and Sassanian exhaustion after prolonged wars allowed Arab tribes to push into frontier zones”; “plague reduced population and weakened tax revenues, making territories vulnerable”).

5–6 marks: Developed explanation with range and depth, covering multiple factors (e.g. political disunity, military exhaustion, plague, weakened frontier states like the Ghassanids and Lakhmids) and explicitly linking them to Arab expansion and the rise of Islam.

(Maximum 6 marks)