OCR Specification focus:

‘England in 1035; the consequences of Cnut’s death (1035); instability resulting from the continuation of Danish influence (Harold I 1035–1040 and Harthacnut 1040–1042).’

The death of Cnut in 1035 triggered a turbulent period in English politics, marked by rival claims, divided loyalties, and enduring Danish influence at the heart of government.

England in 1035

In 1035, England was a composite kingdom shaped by nearly two decades of Danish rule under King Cnut (1016–1035). Cnut had successfully united England, Denmark, and Norway under his personal kingship, creating a North Sea Empire.

Map of the North Sea Empire under Cnut c. 1028–1035, highlighting England, Denmark and Norway under one ruler. This geographic context explains why succession in 1035 was complicated by commitments outside England. The map includes surrounding polities for orientation. Source

His reign brought a degree of stability to England, with effective governance through the Anglo-Saxon earldoms and a blend of Danish and English administrative traditions. However, his death in November 1035 left the throne without a clear and uncontested successor.

Cnut’s two main heirs, Harthacnut (by Emma of Normandy) and Harold Harefoot (by Ælfgifu of Northampton), each had strong but regionally divided support. Harthacnut was the designated heir to England and Denmark but was absent in Denmark defending his realm from threats, notably from King Magnus of Norway.

Consequences of Cnut’s Death

The immediate consequence of Cnut’s death was a succession crisis. With Harthacnut abroad, a vacuum emerged in English leadership. Emma of Normandy, Cnut’s widow, supported her son Harthacnut’s claim and sought to rule as regent until his return.

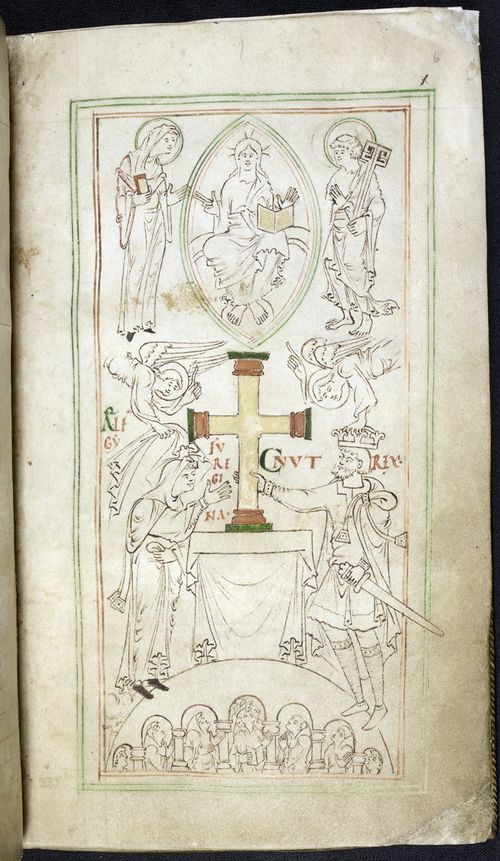

King Cnut and Queen Emma donate a cross to New Minster, Winchester (c. 1031). The image illustrates royal piety and Emma’s visibility in royal ceremonies that underpinned claims to legitimacy in 1035–1042. The liturgical setting exceeds the syllabus detail but clarifies why Emma wielded influence. Source

Conversely, Harold Harefoot had the backing of powerful English nobles, especially in the north and midlands, where Earl Leofric of Mercia and others favoured him as a more immediate and practical ruler.

The Witan (royal council) played a decisive role. It was divided, reflecting the broader political fragmentation of the realm. In late 1035, a compromise was reached: Harold would act as regent over part of the kingdom, while Emma held power in the south for Harthacnut. This arrangement, however, was inherently unstable and quickly collapsed into open rivalry.

Instability from Danish Influence

Harold I “Harefoot” (1035–1040)

Harold’s rule emerged from this contested regency. By 1037, he had consolidated control, forcing Emma into exile in Flanders and declaring himself king. His nickname Harefoot, referring to his swiftness, became a mark of his reputation as a capable military leader, but his reign was marred by insecurity and factionalism.

Key sources describe Harold’s reign as one in which Danish influence persisted but began to fracture:

Many of Cnut’s Danish housecarls and advisors remained in positions of influence.

The earls retained considerable autonomy, reflecting both Anglo-Saxon tradition and Cnut’s power-sharing model.

Harold faced persistent threats from supporters of Harthacnut and from Emma’s allies abroad.

A notorious event of Harold’s reign was the death of Alfred Ætheling, Edward the Confessor’s brother, in 1036 after a failed attempt to return to England. Contemporary accounts accuse Harold’s faction of orchestrating Alfred’s brutal blinding and death, deepening divisions.

Harthacnut (1040–1042)

Harthacnut’s accession in 1040 followed Harold’s sudden death.

Silver penny of Harthacnut, Arm-and-Sceptre type, minted at London (1040–1042). The issue demonstrates continuing royal administration and minting under a Danish dynasty. Legends and the moneyer’s name exceed syllabus detail but corroborate governance continuity. Source

His reign demonstrated the continuation of Danish royal authority but also its limitations in England.

Harthacnut arrived with a fleet of Danish ships, symbolising military dominance but also imposing a heavy naval tax on the population, causing resentment.

His harsh reprisals against opponents, such as the public desecration of Harold’s body, alienated many English nobles.

Administrative continuity persisted: the use of Danish military organisation and the integration of Danes into local governance remained notable features.

Housecarl: A professional, highly trained warrior serving as part of a king’s or noble’s personal bodyguard, prominent in both Anglo-Saxon and Danish military structures.

Harthacnut also faced significant external pressures. As king of both Denmark and England, his attention was divided. Internal discontent and the heavy fiscal burden of maintaining fleets and armies weakened his popularity. His sudden death in 1042 ended the direct Danish royal line in England.

Lasting Impact of Danish Influence

Between 1035 and 1042, England remained profoundly shaped by the legacy of Cnut’s rule:

Political structures blended Anglo-Saxon traditions (e.g., the Witan, shire administration) with Danish models of military and fiscal organisation.

The earls wielded substantial power, acting almost as regional rulers, which could both stabilise and fragment royal authority.

The elite warrior class, especially the housecarls, retained Danish cultural and military practices.

Dynastic politics were entangled with Scandinavian affairs, with English kingship linked to the control of Denmark and, at times, Norway.

These years of instability underscored the fragility of a composite monarchy dependent on personal union and the loyalty of powerful regional magnates. The succession crises, rivalries, and enduring Danish influence set the stage for the reign of Edward the Confessor and the further political upheavals of mid-11th century England.

FAQ

The Witan was the royal council composed of leading nobles, bishops, and earls. In 1035, it was split between supporters of Harold Harefoot and those of Harthacnut.

Rather than immediately electing one king, the Witan brokered a temporary compromise: Harold would act as regent in part of England, while Emma of Normandy held the south for Harthacnut. This arrangement was unstable and eventually collapsed, highlighting the Witan’s political influence but also its inability to maintain unity in a divided kingdom.

Emma was both Cnut’s widow and the mother of Harthacnut, giving her a central position in the succession dispute.

She leveraged her Norman connections to bolster her son’s claim and sought to rule as regent until Harthacnut’s return. Her household at Winchester became a political hub for her allies, and her ability to attract foreign support—particularly from Flanders—made her a serious threat to Harold Harefoot’s authority.

Strengthened alliances with northern earls, especially Leofric of Mercia.

Marginalised Emma of Normandy by forcing her into exile in Flanders.

Utilised Danish housecarls and loyal magnates to secure his position in London.

By 1037, Harold had effectively ended the regency arrangement, declared himself king, and taken full control of England, a move that alienated Harthacnut’s supporters.

Harthacnut arrived in 1040 with a large Danish fleet, which required substantial funding.

To maintain this force, he imposed a heavy naval tax, which was deeply unpopular among the English population. The tax burden not only strained the economy but also damaged relations between the crown and its subjects, contributing to growing discontent during his short reign.

Harthacnut’s sudden death in 1042 ended the direct Danish royal line in England.

Without a Danish-born ruler, political focus shifted towards Anglo-Saxon claimants such as Edward the Confessor. Although Danish cultural and military elements—such as housecarls and administrative practices—remained, the absence of a Scandinavian monarch reduced the political weight of Denmark in English affairs.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks)

In which year did Harold Harefoot become king of all England?

Question 1 (2 marks)

1 mark for identifying the correct year: 1037.

1 additional mark for explaining that this was the year Harold replaced Emma of Normandy as regent and took full control.

Question 2 (5 marks)

Explain two reasons why the death of Cnut in 1035 led to political instability in England.

Question 2 (5 marks)

Award up to 3 marks for each reason, with a maximum of 5 marks in total.

Marks for each reason:

1 mark for identifying a valid reason.

1 mark for providing supporting detail/evidence.

1 mark for explaining how/why this reason contributed to instability.

Indicative content:

Succession dispute: Harthacnut was the designated heir but was in Denmark defending against threats, leaving no uncontested ruler in England (ID + detail + link to instability).

Factional divisions: Supporters of Harold Harefoot (e.g., Earl Leofric of Mercia) clashed with supporters of Harthacnut and Emma of Normandy, dividing the Witan and undermining unity.

Other acceptable answers include: Emma’s attempted regency, regional loyalties splitting north/south, involvement of Scandinavian politics, and the role of the Witan in creating an unstable compromise.