OCR Specification focus:

‘William’s attitude towards the Church; the trial of William of Saint-Calais (1088)’

William II, known as Rufus, had a complex and often confrontational relationship with the Church. His reign was characterised by tension over ecclesiastical authority, royal prerogatives, and the control of Church wealth.

Introduction

William II’s reign was marked by persistent disputes with the Church, stemming from his pragmatic politics, assertive kingship, and readiness to challenge ecclesiastical independence to strengthen royal power.

William II’s General Attitude toward the Church

William Rufus inherited from his father, William the Conqueror, a centralised monarchy in which the king held significant influence over ecclesiastical appointments. However, unlike his father, Rufus often prioritised personal gain over piety, and his approach to the Church reflected this.

Control over appointments: William insisted on retaining bishoprics and abbeys vacant for extended periods, collecting their revenues for the crown. This practice, known as keeping sees in royal custody, increased his income but provoked clerical discontent.

Limited respect for papal authority: William resisted papal interference in English ecclesiastical matters, upholding his father’s policy that no papal letters could be received in England without the king’s consent.

Exploitation of Church resources: William saw Church wealth as a means of financing military campaigns and rewarding loyalty, which sometimes put him at odds with reform-minded clergy.

Papal Authority: The jurisdiction and power claimed by the Pope over the Church, including influence over appointments and discipline.

Conflict with Ecclesiastical Reform

The late 11th century was a time of Gregorian Reform, aiming to free the Church from secular control and enforce clerical celibacy and moral discipline. William’s policies often ran counter to these reforms:

He was slow to appoint reform-minded bishops.

He tolerated, and perhaps encouraged, clergy who were loyal to him regardless of their adherence to reform.

He resisted measures that might reduce royal influence over the Church.

The Trial of William of Saint-Calais (1088)

The trial of William of Saint-Calais, Bishop of Durham, illustrates William II’s determination to assert royal authority over senior churchmen.

Background

In 1088, a rebellion broke out against William led by Norman barons dissatisfied with his rule.

William of Saint-Calais, a trusted royal adviser and influential northern magnate, was accused of treason for allegedly supporting the rebels and refusing to assist the king militarily.

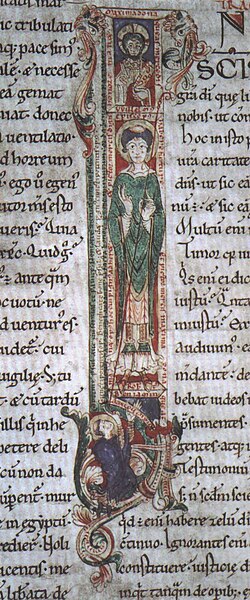

Contemporary illumination showing William of St-Calais within a decorated initial from an 11th-century copy of Augustine’s Commentary on the Psalms. The kneeling figure at his feet is the manuscript’s scribe. This image directly supports discussion of St-Calais’s standing at court and in the Church. Source

His defence rested on the claim that, as a bishop, he was subject only to ecclesiastical law in such matters, not to a secular court.

Treason: The crime of betraying one’s sovereign or country, especially by attempting to overthrow the government.

The Proceedings

William II insisted that the trial be conducted in a secular court (the king’s court), not a Church court, affirming his jurisdiction over bishops in temporal matters.

Old Sarum, the hillfort and Norman stronghold above Salisbury, where the king’s court met in 1088 to try Bishop William of St-Calais. The earthworks and inner bailey convey the imposing, militarised context of a secular hearing. Extra detail: the image shows the broader site; the specific courtroom space is not visible. Source

The king’s justiciars summoned Saint-Calais to answer charges before the lay magnates.

Saint-Calais appealed to canon law and papal authority, but William refused to recognise the appeal, reinforcing the principle that bishops held temporal lands from the king and owed him feudal service.

Outcome

The court found Saint-Calais guilty of treason. His lands and bishopric were confiscated, and he was allowed to leave England.

The verdict sent a clear message: bishops, like other tenants-in-chief, were bound by feudal obligations to the crown and could be tried in royal courts for offences relating to their temporal duties.

Engraved depiction of the Great Seal of William II (Rufus), the emblem affixed to writs and charters to enact the king’s will. It illustrates the monarch’s secular authority over all tenants-in-chief, including bishops. Extra detail: this is a 19th-century engraving of a medieval seal, used here to clarify symbolism. Source

Significance of the Trial

The trial was significant for both royal and ecclesiastical authority in England.

For the Crown:

It confirmed the king’s authority over all landholders, regardless of clerical status.

It demonstrated that ecclesiastical office did not grant immunity from secular justice in temporal matters.

It deterred future clerical dissent by showing the risks of opposing the crown.

For the Church:

It exposed tensions between canon law and feudal law in England.

It alarmed reformers, who saw the verdict as undermining ecclesiastical independence.

It created a precedent that the crown could exploit in later disputes with churchmen.

William II’s Broader Ecclesiastical Policy

William’s reign saw a continuation of the crown’s dominance over the Church but with greater emphasis on financial exploitation than under his father.

He frequently clashed with reformist clergy who sought to reduce secular interference.

His approach laid the groundwork for later conflicts under his brother Henry I, particularly concerning the Investiture Controversy.

Investiture Controversy: A conflict between the papacy and secular rulers over who had the authority to appoint (invest) bishops and abbots.

Key Features of William II’s Church Relations

Pragmatism over principle: Religious policy was driven more by political expediency and revenue needs than by theological commitment.

Assertion of royal supremacy: The king insisted on controlling communications with the papacy and on his right to try bishops in secular courts.

Integration of Church into feudal hierarchy: Bishops were treated as barons, with military and fiscal obligations to the crown.

Consequences for the English Church

The Church under William II became a tool of royal policy, with reduced autonomy.

Clerical morale and reform efforts were weakened by the crown’s interference.

The tensions created by his rule would resurface under Henry I in disputes with Archbishop Anselm.

FAQ

William of St-Calais was Bishop of Durham, a post that combined both spiritual and military responsibilities. Durham’s location in the north made it strategically vital against Scottish threats.

He was also a close adviser to William II in the early years of his reign, involved in administrative and legal decisions. His combination of ecclesiastical authority and regional power made his defection during the 1088 rebellion particularly damaging to the king’s position.

The rebellion posed a serious threat to William II’s throne, led by powerful Norman magnates aiming to replace him with his elder brother, Robert Curthose.

In this tense context, prosecuting St-Calais served two purposes: punishing a high-profile alleged traitor and deterring other potential defectors. The trial reinforced the idea that no one, not even a bishop, was beyond the reach of royal justice during a crisis.

They argued that bishops held extensive temporal lands from the king in return for military and financial obligations under the feudal system.

Because the case related to failure in these temporal duties—providing military aid in a rebellion—the king’s court, not an ecclesiastical one, had jurisdiction. This legal reasoning blurred the line between the bishop’s spiritual office and his role as a feudal baron.

The reaction was mixed. Some bishops supported St-Calais’s argument that a churchman should only be tried by ecclesiastical authority, fearing for their own autonomy.

Others, particularly those loyal to Rufus or wary of challenging him during the rebellion, accepted the king’s jurisdiction. This division weakened the collective ability of the episcopate to resist royal control in future disputes.

Yes. After St-Calais’s exile, Durham remained without a bishop for several years, allowing William II to draw revenue directly from its estates.

When St-Calais was restored in 1091 after reconciliation with the king, the precedent of royal authority over the see lingered. This episode cemented Durham’s importance as both a spiritual and political office in the Anglo-Norman realm.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks)

In which year did the trial of William of St-Calais take place, and what was the principal charge against him?

Mark scheme:

1 mark for correctly stating 1088 as the year.

1 mark for identifying the principal charge as treason (accept “supporting the rebellion against William II” or equivalent wording).

Question 2 (5 marks)

Explain two ways in which the trial of William of St-Calais demonstrated William II’s attitude towards the Church.

Mark scheme:

Award up to 5 marks:

1–2 marks for each valid point identified and explained (maximum 2 points).

1 additional mark for depth of explanation in at least one point.

Indicative content (credit any other valid points):

William II insisted the trial be held in a secular court, showing his belief that bishops could be judged under royal jurisdiction in temporal matters. (1 mark for identification, 1 mark for explanation linking to assertion of royal authority.)

Refusal to accept William of St-Calais’s appeal to canon law and papal authority, highlighting Rufus’s resistance to papal interference. (1 mark for identification, 1 mark for explanation linking to control over ecclesiastical matters.)

The confiscation of St-Calais’s lands and bishopric demonstrated William’s readiness to use Church positions for political control. (1 mark for identification, 1 mark for explanation.)