OCR Specification focus:

‘anti-clerical developments, causes, nature and reasons for the growth of Lollardy; the Oldcastle Rebellion (1414) and its impact; the burning of John Badby’

Richard II’s successor, Henry V, faced major challenges from religious dissent. In particular, Lollardy—rooted in the teachings of John Wycliffe—posed both ideological and political threats.

Background to Lollardy

Lollardy emerged in the late fourteenth century as a movement critical of the wealth and corruption of the medieval Church. It drew from the ideas of John Wycliffe, Oxford scholar and reformer, who advocated reform in doctrine and practice.

Lollardy: A religious reform movement inspired by John Wycliffe, calling for vernacular scripture, rejection of transubstantiation, and opposition to clerical wealth and privilege.

By Henry V’s accession in 1413, the Lollards had gained traction among both intellectual circles and sections of the urban population. Their ideas were perceived as threatening not only to the Church but also to the monarch, whose legitimacy was intertwined with ecclesiastical authority.

Anti-Clerical Developments under Henry V

Henry V inherited a kingdom where anti-clerical sentiment was widespread. This was linked to resentment against:

The wealth of the clergy, particularly the higher orders such as bishops and abbots.

Perceptions of corruption and worldliness within the Church hierarchy.

Concerns about clerical privileges, including exemption from certain taxes and trials.

These tensions provided fertile ground for Lollardy. Demands for reform included:

Translation of the Bible into vernacular English.

Condemnation of the doctrine of transubstantiation.

Rejection of pilgrimages, saints, and images, seen as superstitious practices.

Calls for the seizure of church lands to redistribute wealth.

Although such demands resonated with elements of society, they also attracted harsh opposition from both the Church and the Crown.

Causes and Nature of Lollard Growth

The Lollard movement expanded for several reasons:

Intellectual support: Wycliffe’s Oxford background gave credibility to reformist arguments.

Textual dissemination: Hand-copied vernacular Bibles spread Lollard ideas.

Urban support: Merchants, artisans, and London guild members found its anti-clericalism appealing.

Noble sympathy: Some knights and nobles, such as Sir John Oldcastle, adopted Lollard views.

However, the movement remained diverse in character. Some followers pressed for quiet reform, while others leaned toward radical dissent, challenging both church and state authority.

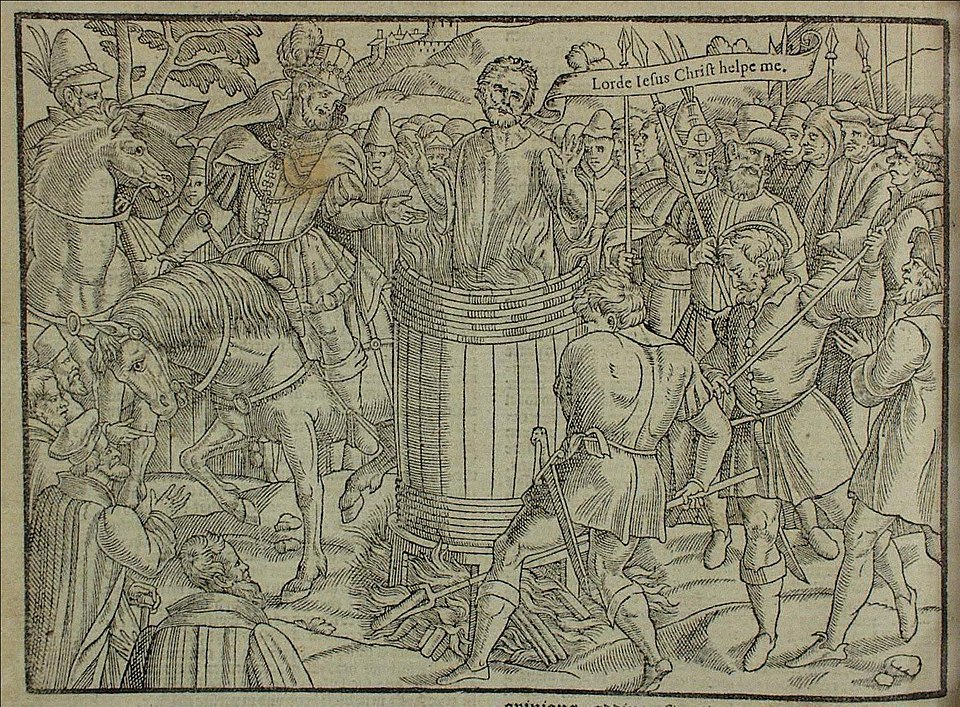

Sir John Oldcastle and the Rebellion of 1414

Sir John Oldcastle, a close associate of Henry V and former companion-in-arms, became the most prominent noble supporter of Lollardy. Initially shielded by his royal connections, he was eventually arrested for heresy in 1413 but escaped imprisonment.

The Oldcastle Rebellion

In January 1414, Oldcastle organised a plot to overthrow Henry V. The aim was to:

Seize the King at Eltham Palace.

Install a Lollard-inspired regime that would diminish clerical power.

Promote religious reform across England.

The rebellion was poorly coordinated and quickly suppressed. Henry’s forces crushed the insurgents at St Giles’ Fields near London. Oldcastle fled but was captured and executed in 1417.

Oldcastle Rebellion: A failed Lollard rising in January 1414 led by Sir John Oldcastle, aiming to seize Henry V and impose religious reform.

Sir John Oldcastle (Lord Cobham) is shown executed by burning after the failed 1414 Lollard rebellion. While the scene itself is 1417 (slightly outside 1413–1414), it directly illustrates the consequences of the revolt specified for study. Use to reinforce the link between dissent and treason in Henry V’s reign. Source

The rebellion demonstrated that Lollardy was no longer only an intellectual or religious challenge but also a direct political threat to royal authority.

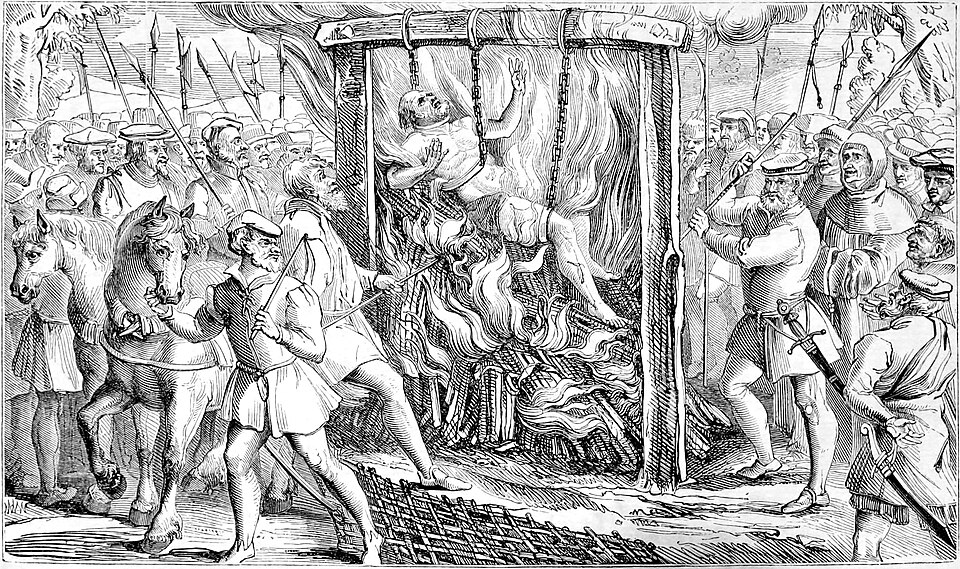

The Burning of John Badby

The Lollard movement faced severe persecution. A notable example was John Badby, a craftsman tried for heresy in 1410. He denied the doctrine of transubstantiation, which held that the bread and wine of the Eucharist became the body and blood of Christ.

Transubstantiation: The Catholic doctrine that during the Mass, the bread and wine are transformed into the actual body and blood of Christ, while retaining their outward appearance.

Badby’s refusal to recant led to his execution by burning—one of the earliest instances of such punishment for heresy in England.

John Badby is depicted being burned in a barrel (Smithfield, 1410) for rejecting transubstantiation. Contemporary woodcut imagery underscores how heresy was punished publicly to deter dissent. The image includes period detail not required by the syllabus (onlookers and apparatus) but accurately illustrates the event named in the specification. Source

His death underscored the determination of both Church and Crown to suppress dissent.

Impact of the Oldcastle Rebellion and Lollard Persecution

The consequences of Lollardy and its suppression were far-reaching:

Increased repression: The rebellion justified harsh legislation against heresy, including expanded powers for Church courts.

Association with treason: Lollardy was redefined not merely as heresy but as treason against the Crown.

Decline of open support: Many former sympathisers abandoned the cause for fear of persecution.

Survival underground: Despite repression, Lollard ideas persisted clandestinely, influencing later religious dissenters such as the Protestant reformers of the sixteenth century.

Henry V’s decisive suppression of Lollardy reinforced his image as a defender of the faith and a monarch firmly aligned with the established Church. This alignment was politically advantageous, ensuring the clergy’s loyalty during his French campaigns.

Conclusion on Religious Dissent, 1413–1414

In 1413–1414, Henry V faced a convergence of religious and political dissent. The growth of Lollardy, fuelled by anti-clericalism and social grievances, culminated in the dramatic Oldcastle Rebellion. Its failure, combined with the shocking execution of John Badby, marked a turning point in the treatment of heresy in England. Lollardy became synonymous with treason, shaping the course of both religious policy and political stability under Henry V.

FAQ

Oldcastle’s close ties to the nobility and his previous service alongside Henry V gave the rebellion a sense of legitimacy and potential for wider support.

His status as Lord Cobham meant he had influence among other knights and retainers, raising fears that disaffected nobles could rally to his cause. This distinguished the rebellion from purely urban or popular unrest, amplifying its perceived threat.

Henry acted swiftly, using both military force and legal measures. The speed of suppression demonstrated his determination to eliminate threats before they spread.

He also linked heresy to treason, ensuring rebels were not only condemned religiously but also politically. This dual strategy set a precedent for dealing with religious dissent under his reign.

London was the political and economic heart of England, home to Parliament, royal palaces, and major Church institutions.

Controlling London would have allowed rebels to:

Capture Henry V and destabilise government.

Spread Lollard ideas more effectively among urban artisans and guilds.

Undermine both Crown and Church simultaneously.

Its centrality meant even a failed rising there caused major alarm.

Following 1414, Lollardy did not disappear but was forced underground.

Open gatherings became rare due to harsh repression.

Networks of sympathisers persisted in urban centres, especially London and the Midlands.

Ideas survived in manuscript circulation and oral teaching, influencing later reform movements.

The rebellion’s failure meant the movement’s political ambitions ended, but its religious dissent endured.

Badby’s execution in 1410 was highly public and intended as a warning. Accounts suggest Henry, then Prince of Wales, personally attended and offered Badby a pardon if he recanted.

His refusal highlighted Lollard conviction, but his death reinforced the message that heresy would not be tolerated. For some observers, Badby became a martyr figure, strengthening underground sympathy for Lollard beliefs.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks):

What was the central belief about the Eucharist that John Badby rejected, leading to his execution in 1410?

Mark Scheme:

1 mark for identifying the doctrine of transubstantiation.

1 mark for explaining it meant that the bread and wine literally became the body and blood of Christ.

Question 2 (6 marks):

Explain two reasons why the Oldcastle Rebellion of 1414 posed a serious threat to Henry V’s authority.

Mark Scheme:

Award up to 3 marks for each reason, with clear explanation needed for full marks.

Noble leadership (up to 3 marks): Sir John Oldcastle was a knight and close former ally of Henry V, giving the rebellion credibility and showing dissent could spread into the nobility. (1 mark for identifying Oldcastle, up to 2 more for explaining his significance).

Challenge to monarchy and Church (up to 3 marks): Rebels aimed to seize Henry and impose Lollard reforms, which directly threatened both the Crown and the established Church. (1 mark for identifying seizure aim, up to 2 more for explanation of why this undermined authority).

Alternative valid reasons may include:

Location and timing near London heightened danger.

Movement tied to wider anti-clericalism, making suppression urgent.

Marks awarded according to accuracy, relevance, and depth of explanation.