OCR Specification focus:

‘the social, economic and political conditions that encouraged the development of the Renaissance; artistic development in Venice; the importance of printing and education.’

Venice around 1400 was uniquely placed to nurture the Renaissance. Its prosperity, political structures, and distinctive society enabled the city to become a leading cultural powerhouse.

Social Conditions

Urban Structure and Society

Venice was a maritime republic with a strong civic identity shaped by its lagoon setting. Its population was diverse, including nobles, merchants, artisans, and immigrants from across Europe and the eastern Mediterranean. This cosmopolitan environment encouraged the exchange of ideas, goods, and cultural influences.

The patriciate (hereditary nobility) dominated political life through the Great Council.

A wealthy mercantile class supported trade and patronage, funding churches, schools, and art.

Guilds (known as arti) regulated trades and crafts, providing education and supporting artistic commissions.

Education and Literacy

Education in Venice reflected humanist trends while remaining practical. Boys of elite families attended Latin schools, while merchant families prioritised training in mathematics and languages for trade. The city valued literacy, which supported the growth of publishing and record-keeping in commerce.

Humanism: A cultural and intellectual movement of the Renaissance that emphasised the study of classical texts, human potential, and secular learning.

Humanist schools emerged under the influence of figures such as Vittorino da Feltre, spreading ideals of the Renaissance man — well-educated, articulate, and morally grounded.

Economic Conditions

Trade and Commerce

Venice’s wealth rested on its dominance of Mediterranean trade. Control of sea routes and connections with the Byzantine and Islamic worlds gave access to luxury goods such as spices, silks, and precious metals. This wealth provided the capital for artistic and architectural patronage.

Merchant families like the Mocenigo and Loredan funded civic projects.

Trade revenues sustained cultural investment, making Venice less dependent on princely patrons compared to Florence or Milan.

Venice’s maritime economy relied on long-distance trade through the Stato da Mar, funnelling spices, grain and luxury goods between the Levant and northern Europe.

Map of late-medieval European trade routes with Venetian sea-lanes in blue and Genoese in red. It shows Venice’s Adriatic and eastern Mediterranean corridors linking to northern markets. The key clarifies overlapping routes used by both powers. Source

Printing and Publishing

The arrival of printing in Venice in 1469 transformed cultural life. Venice quickly became Europe’s leading centre for publishing due to its skilled workforce and trade links.

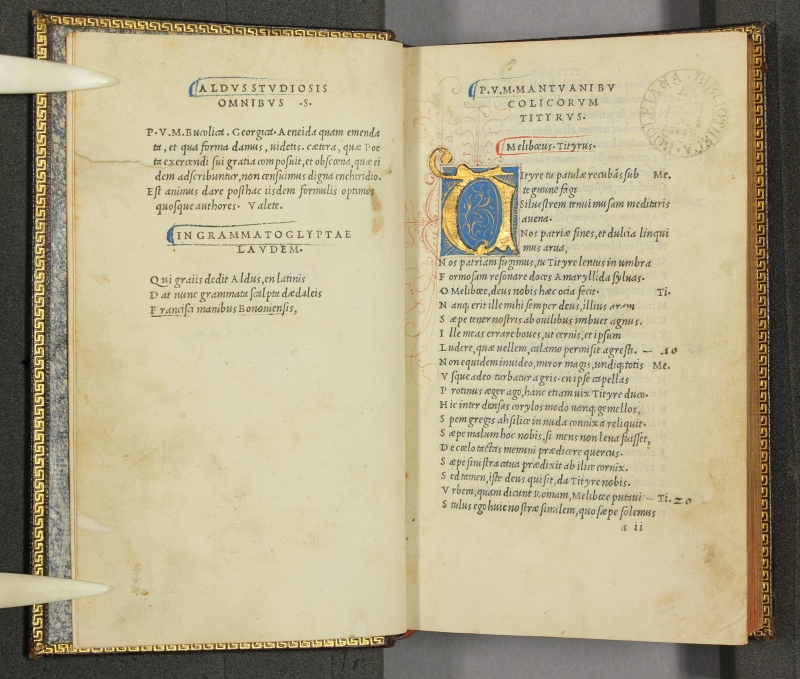

Aldus Manutius, a pioneering printer, produced inexpensive, portable editions of classical texts and works of humanist scholarship.

The city became a hub for intellectual exchange, distributing works across Europe.

Printing helped standardise texts and spread Renaissance ideas beyond elite circles.

Renaissance man: An individual skilled in multiple fields of knowledge and arts, embodying the Renaissance ideal of broad education and accomplishment.

Printing reinforced this ideal by making humanist texts more widely available.

Venice became Europe’s leading printing centre by the 1490s; Aldus Manutius popularised italic type and the portable octavo, broadening access to humanist texts.

Aldine Virgil (Eclogues, 1501), a landmark Venetian edition introducing italic type and pocket-sized octavo books. These innovations supported wider reading among scholars and educated urbanites. The source page includes further curatorial commentary beyond syllabus scope. Source

Political Conditions

The Stability of the Republic

Venice’s government was an oligarchic republic, balancing power between the Doge, the Senate, and the Great Council. Its stability contrasted with the turmoil in other Italian states.

Political continuity and security encouraged investment in long-term artistic and cultural projects.

Civic pride drove public works, such as the decoration of the Doge’s Palace and construction of grand churches.

The Myth of Venice

Venetians cultivated the idea of their city as a divinely favoured republic, a “New Rome.” This myth shaped cultural patronage:

Artworks emphasised the glory of Venice rather than individual rulers.

Religious and civic art blended to reinforce the city’s reputation for piety, stability, and justice.

Unlike Florence, where patrons often glorified their families, Venice stressed collective identity.

Artistic Development

Venetian Artistic Style

Venetian art developed distinctive characteristics compared to other Italian centres. The city’s location and wealth of materials shaped its style:

Colour and light were emphasised, aided by oil paints introduced from Northern Europe.

The use of canvases (cheaper and more practical than fresco) flourished in Venice’s damp climate.

Artists such as Giovanni Bellini pioneered naturalistic and luminous works.

Patronage

Artistic development in Venice relied on both civic and religious commissions. Unlike Florence, dominated by private patrons such as the Medici, Venice highlighted collective and institutional patronage:

Scuole Grandi (lay confraternities) commissioned altarpieces and narrative cycles.

The state sponsored decoration of civic buildings.

Religious orders funded works to demonstrate piety and social influence.

The Scuole Grandi (major lay confraternities) organised charity, education and civic ritual, and acted as powerful patrons of art across the city.

Interior view of the Scuola Grande di San Rocco, a leading confraternity hall. Such spaces hosted religious observance, welfare activity, and major cycles of commissioned art, integrating civic piety with cultural patronage. Extra details visible (ceiling decoration) go beyond the syllabus but help illustrate the grandeur of confraternal settings. Source

Integration of Culture

Venetian art reflected its cultural crossroads. Contacts with the East brought new motifs, while trade in pigments ensured access to vibrant colours like ultramarine. Artists integrated classical themes with local traditions, reflecting both humanist ideals and the city’s unique identity.

The Importance of Education

Venice’s cultural life was tied to the growth of education, closely linked to printing and humanism. Schools prepared both elites and merchants for civic life:

Humanist education emphasised rhetoric, philosophy, and classical languages.

The spread of printed books reinforced education, making literary culture more accessible.

Education created a broader audience for Renaissance art and ideas, embedding them into Venetian society.

Scuole Grandi: Powerful Venetian lay confraternities that combined charitable, religious, and cultural functions, often commissioning significant works of Renaissance art.

These institutions illustrate how education, piety, and artistic development were interwoven in Venice’s Renaissance society.

FAQ

Venice attracted Greeks, Germans, and Jews, who brought skills, ideas, and cultural traditions. The Greek community, for example, contributed to the preservation and transmission of classical texts, especially after the fall of Constantinople.

Immigrants often formed distinct quarters, such as the Fondaco dei Tedeschi for German merchants, which fostered both trade and cultural exchange. These groups helped make Venice a cosmopolitan hub, blending diverse influences into its Renaissance identity.

The lagoon setting provided natural defence and easy access to maritime routes. Venice controlled choke points in the Adriatic and established colonies, known as the Stato da Mar, which secured resources and trade routes.

Its position made it a key link between the East and West. This geographic advantage enabled the city to accumulate wealth, which directly financed cultural and artistic patronage.

Venice had:

A large, literate mercantile population creating high demand.

Strategic access to trade routes, allowing books to be exported across Europe.

A concentration of skilled artisans, typesetters, and scholars.

The city also attracted investors willing to support printing ventures. As a result, Venice produced more books by 1500 than any other European city, making it the continent’s publishing capital.

Unlike Florentine patronage, dominated by powerful families like the Medici, Venetian cultural sponsorship was largely communal. The Scuole Grandi funded major artistic cycles to benefit members and enhance civic piety.

This emphasised collective identity rather than individual prestige. The confraternities’ projects often depicted religious themes aligned with Venice’s civic myth, reinforcing unity across society.

Venetian artists pioneered the use of oil paints on canvas rather than fresco. Canvases were more durable in the damp climate and allowed for larger works.

They also had access to imported pigments via trade. Colours such as ultramarine, made from lapis lazuli, gave Venetian paintings their renowned richness. Combined with a focus on light and atmosphere, these techniques distinguished Venetian art from Florentine emphasis on linear perspective.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks)

Identify two ways in which the Scuole Grandi contributed to cultural life in Renaissance Venice.

Mark Scheme:

1 mark for each correct contribution identified (maximum 2 marks).

Possible answers:

Commissioning major works of art.

Organising religious observance and charitable activities.

Supporting education and civic ritual.

Question 2 (6 marks)

Explain how the economic conditions of Venice encouraged the development of the Renaissance in the fifteenth century.

Mark Scheme:

Award up to 6 marks for explanation and development of points

1–2 marks: Simple statements or generalised description (e.g., “Venice was wealthy” without further explanation).

3–4 marks: Some explanation of specific factors (e.g., “Trade with the East brought luxury goods which gave Venice the wealth to fund art and architecture”).

5–6 marks: Developed explanation showing clear understanding of links between economy and Renaissance development (e.g., “Venice’s control of Mediterranean trade routes provided huge revenues, which merchant families like the Mocenigo used to commission public works. Wealth also enabled the city to attract artists and sustain a large printing industry, spreading humanist culture”).