OCR Specification focus:

‘Economic pressures, social structure, change and division prompted scapegoating and persecution.’

Economic hardship, shifting social structures, and tensions in community life were crucial in fuelling witchcraft accusations, as fears, resentments, and instability often sought scapegoats.

Economic Pressures and Witchcraft Persecution

The 16th and 17th centuries were periods of significant economic volatility. Population growth, inflation, and recurring harvest failures created an environment of scarcity and fear. In many regions, subsistence agriculture could barely provide for communities. Economic stress translated into social tension, particularly when communities sought to explain hardship by attributing it to the malicious agency of witches.

Inflation and Poverty

The rapid growth in population during this period placed strain on resources.

Prices of basic goods, especially grain, rose significantly, leaving poorer households vulnerable.

Weekly rye and barley prices from Cologne across the sixteenth century demonstrate both rising price levels and increased volatility. Such instability strained subsistence budgets and fuelled resentments that could be channelled into scapegoating. The chart’s focus on staple grains directly illustrates how economic pressure translated into social tension. Source

Economic inequality increased, creating resentment between those who were able to adapt and those left in dire poverty.

The perception that marginal individuals—often the poor, widows, or elderly women—could harm others’ economic well-being contributed to the rise in prosecutions. When misfortune struck, communities were quick to attribute losses to supposed witchcraft.

Social Structure and Community Divisions

Hierarchical Society

The social hierarchy of early modern Europe placed heavy emphasis on order and conformity. At the top stood nobles and clergy, while peasants and labourers formed the bulk of society. Such rigid stratification meant that resentment and suspicion could easily develop between classes.

Breakdown of Communal Solidarity

The customary support systems of rural life began to weaken as economic and social pressures increased:

Traditional practices such as charitable giving to the poor became less consistent as resources dwindled.

Those left unsupported, such as elderly widows, often became associated with malevolent supernatural influence.

Communities fragmented under the strain of repeated crises, weakening trust between neighbours.

Scapegoating: The process of blaming individuals or groups for broader social, economic, or political problems, often diverting responsibility from structural causes.

This scapegoating dynamic was central to the persecution of witches, where marginalised people became the focus of collective anxiety.

The Role of Change and Division

Rural versus Urban Communities

In rural communities, economic survival depended heavily on the harvest.

Ridge-and-furrow ridges mark the long, narrow strips cultivated in the open-field system. The pattern reflects shared labour and interdependence within villages before enclosure consolidated holdings. (Extra detail: the file page includes licensing and camera metadata not required by the syllabus.) Source

In urban settings, competition for trade and work heightened tensions, sometimes leading to witchcraft accusations against rivals.

The stresses of economic change, such as the gradual shift toward market economies and away from feudal ties, further destabilised traditional relationships. As change deepened, conflict between old and new social expectations became fertile ground for witch-hunting.

Enclosure and Displacement

The enclosure movement—where common lands were converted into private holdings—displaced many peasants.

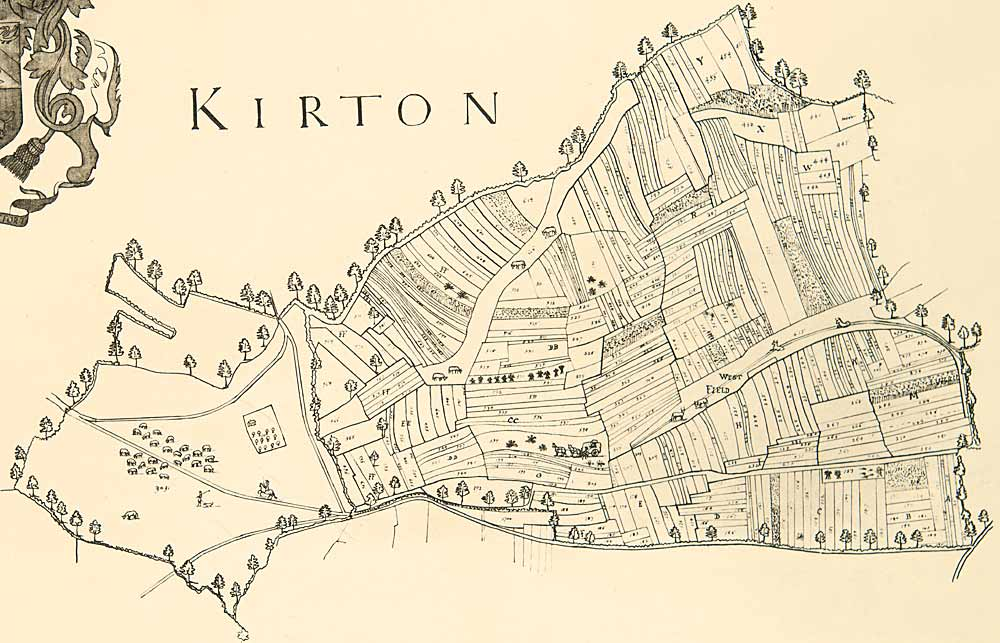

Mark Pierce’s 1635 plan of Laxton shows thousands of narrow strips radiating from the village, a classic open-field pattern that structured labour, tenure, and neighbourly reciprocity. Such dispersed holdings shaped obligations and tensions within rural communities. The map provides concrete context for why enclosure represented a disruptive social and economic change. Source

Dispossession and migration fuelled instability, and displaced individuals often appeared threatening to settled communities. Such people were prime candidates for witchcraft accusations, as they embodied economic disruption.

Vulnerable Groups and Accusations

Women and the Poor

The majority of those accused of witchcraft belonged to groups already marginalised by social and economic status:

Widows, who lacked male protection and often relied on charity.

Older women, whose declining productivity in agricultural economies made them economically vulnerable.

The impoverished, whose dependency on neighbours or parish relief could turn to resentment when aid was refused.

The connection between gender, poverty, and suspicion was reinforced by cultural beliefs associating women with weakness, moral frailty, and susceptibility to the Devil.

Social Relations and Tensions

Neighbourly quarrels, disputes over resources, or perceived failures of reciprocity frequently led to accusations:

If a beggar was refused alms and the household later suffered misfortune, suspicions of witchcraft followed.

Accusations often emerged in close-knit communities where tensions simmered over time.

Scapegoating in Times of Crisis

Periods of war, famine, or epidemic disease intensified the need for explanations. In such contexts:

Communities sought control and order by targeting perceived sources of harm.

Witch trials provided a visible means of reasserting social discipline in times of upheaval.

Persecution offered authorities a way to channel popular anger toward individual scapegoats rather than systemic failings.

Persecution: The systematic mistreatment of individuals or groups, often based on identity, beliefs, or perceived threats, in this context through legal and cultural mechanisms of witch-hunting.

Authorities reinforced persecution by adopting local suspicions, transforming communal accusations into formal trials.

The Link Between Authority and Social Order

While economic stress and social division fuelled suspicion at the community level, authorities often amplified these dynamics:

Local magistrates and clergy exploited witchcraft accusations to reinforce social conformity.

Persecutions were sometimes used to divert discontent away from rulers’ failure to alleviate economic hardship.

By prosecuting witches, authorities projected an image of restoring order amidst instability.

This interplay between popular fears and institutional responses embedded witchcraft persecution into the social fabric of the 16th and 17th centuries.

FAQ

Poor harvests meant food shortages, price spikes, and widespread hunger. Communities often viewed these crises as unnatural misfortunes rather than cyclical events.

Neighbours suspected those on the margins, such as widows or beggars, of causing crop failures through curses or maleficium. In this way, harvest failures acted as a direct trigger for accusations.

Widows lacked male protection and legal standing in many communities. Without husbands, they often relied on neighbours for food or resources.

When aid was refused, tensions rose. If misfortune followed, the widow’s request and subsequent quarrel provided a narrative that she had caused harm, making her an easy scapegoat.

Traditional expectations of almsgiving declined under economic pressure. Families increasingly prioritised their own survival over supporting the poor.

This withdrawal of aid heightened resentment. The refusal of charity was frequently followed by suspicions if misfortune occurred, leading to accusations against those previously dependent on relief.

Enclosure transformed open fields into private plots, displacing peasants and breaking communal ties. This created landless labourers who appeared threatening to settled villagers.

The presence of outsiders disrupted social stability. Their marginal status made them more likely to be targeted in witchcraft accusations, especially when economic conditions worsened.

While rural accusations often centred on harvest and livestock losses, urban accusations had different triggers.

Competition between artisans and traders could turn into witchcraft disputes.

Economic rivalry in towns produced hostility that was explained through alleged supernatural harm.

Thus, both rural and urban settings linked accusations to economic stress, but the specific causes varied by environment.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks)

Identify two groups most vulnerable to accusations of witchcraft during times of economic stress in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying each valid group, up to a maximum of 2.

Acceptable answers include:

Widows

Elderly women

The poor/impoverished

Displaced peasants following enclosure

Question 2 (6 marks)

Explain how economic change and social division contributed to the growth of witchcraft accusations in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Mark scheme:

Level 1 (1–2 marks): Generalised description with little direct reference to economic or social change (e.g. “People blamed witches when things went wrong”).

Level 2 (3–4 marks): Some explanation with at least one developed example (e.g. “Harvest failures and rising grain prices meant communities were quick to suspect the poor or beggars of witchcraft”).

Level 3 (5–6 marks): Clear and developed explanation with two or more examples linking economic stress and social division to accusations (e.g. “Enclosure displaced peasants, creating instability and mistrust, while inflation made the poor dependent on charity, and those refused aid were often suspected of causing misfortune”).