AP Syllabus focus:

‘For square cross sections, students express the side length as a function of x or y, use the area formula for a square, and integrate that area to find the volume.’

Solids with known square cross sections provide a powerful introduction to geometric volume accumulation, allowing students to connect cross-sectional geometry with integral expressions representing infinitely many thin slices.

Understanding Square Cross-Sectional Solids

A solid with square cross sections is built from a base region in the plane and identical–but varying–shapes perpendicular to an axis. As the position moves along the chosen axis of integration, each slice of the solid has a square geometry whose dimensions depend on the underlying base.

When the notes refer to a cross section, the term describes a two-dimensional slice of a solid perpendicular to a coordinate axis.

Cross Section: A planar slice of a three-dimensional solid taken perpendicular to a chosen axis, whose shape and size can vary with position.

A solid’s square cross sections arise when the base region’s width, measured along a perpendicular direction, becomes the side length of each square slice. Because this side length changes with the location along the axis, integration is necessary to combine all slices into a total volume.

For square cross sections, the side length at position x is determined by the width of the base region at that x, so each slice has area [side length]².

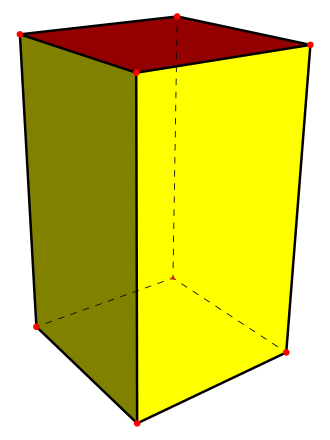

Square prism with all cross sections perpendicular to the long axis forming congruent squares. This model illustrates a solid whose volume can be computed by integrating square cross-sectional areas along the axis. In AP Calculus AB, more general solids with square cross sections may have side length that varies with or , but the same slicing idea applies. Source.

Expressing Side Length as a Function

The construction of such volume problems relies on representing the side length of each square slice as a function of the variable of integration. This function is determined entirely by the geometry of the base region. If the solid is sliced perpendicular to the x-axis, the side length depends on ; if sliced perpendicular to the y-axis, it depends on .

Side-Length Function: A function that assigns to each input position along the axis of integration the length of the square’s side at that location.

The functional expression for side length reflects the distance between two boundary curves (if oriented perpendicular to the x-axis) or between two inverse functions (if perpendicular to the y-axis). Students must understand that this distance directly becomes the dimension of each square’s edges.

A well-defined side-length function guarantees that each cross section is square, meaning all edges are equal and the area formula remains consistent across the interval of integration.

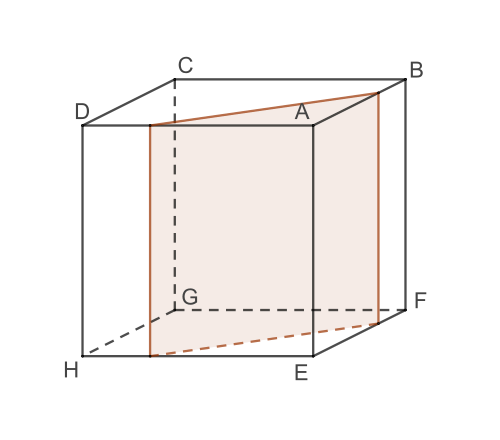

Thinking of a cube being sliced by parallel planes helps visualize how each square cross section contributes a thin ‘layer’ of volume to the entire solid.

Cube cut by a plane so that the resulting cross section is a square. This picture emphasizes that a three-dimensional volume can be analyzed by studying the shapes and areas of its planar cross sections. The diagram includes geometric detail beyond the AP Calculus AB syllabus (such as the orientation of the cutting plane), but only the idea of a square cross section is needed here. Source.

Using the Square Area Formula in Volume Problems

Every square cross section’s area depends solely on its side length. The area must adapt to changes in the underlying base region as the input variable changes. Because the side length determines the size of each square, students use the square area formula to represent the slice area at any point.

= Area of a square cross section (square units)

= Side-length function defined by the base (units)

Between this formula and the geometric interpretation of the base region, the integral for the solid’s volume is formed by accumulating square areas along the axis of integration.

The choice between integrating with respect to or depends on how the base region is described. When the boundaries of the base are naturally expressed as functions of , perpendicular slices yield side lengths based on vertical distances; when the region is better expressed with functions of , horizontal distances define the side length instead.

Constructing the Volume Integral

To obtain the total volume, students combine the cross-sectional areas over the entire interval for which the solid exists. This formulation follows the general principle that volume arises from accumulating infinitesimal slices of area.

= Total volume of the solid (cubic units)

= Area of the square cross section at position (square units)

= Bounds of the interval describing the base region (units)

A similar expression is used when slicing perpendicular to the y-axis, replacing with and with . In each case, the integral adds infinitely many square areas, capturing the continuous variation in side length across the base region.

You can picture the solid as being built from many thin square slabs stacked along the chosen axis, each slab having side length given by the base-region function.

Axonometric view of a square prism, highlighting a solid with a square base and parallel square faces. This supports the interpretation of volume as the accumulation of square cross-sectional slices. The image does not depict a specific function or coordinate axes, so it serves as a geometric model for the slicing idea used in AP Calculus AB. Source.

Applying Cross-Sectional Reasoning

Working with square cross sections helps students develop intuition about how geometry interacts with integration. Because solids in this category rely on uniform shape but variable size, they exemplify the broader concept of volume as accumulated area. Key skills reinforced in this subsubtopic include:

Identifying the axis of integration based on the most natural description of the base region.

Determining the side-length function from boundary curves or endpoints.

Applying the square area formula using the side-length function.

Setting up a definite integral that accumulates the areas of all square slices.

Interpreting the definite integral as the total three-dimensional volume built from infinitely many cross sections.

These techniques empower students to handle a wide variety of solids whose structure derives from geometric rules combined with the fundamental ideas of accumulation and integration.

FAQ

You choose the variable of integration based on the direction in which the cross sections are taken. If the slices are perpendicular to the x-axis, integrate with respect to x; if they are perpendicular to the y-axis, integrate with respect to y.

A practical way to decide is to check which orientation keeps the side-length function expressed as a single, continuous distance between two curves. Whichever variable makes that distance easier to express should be used in the volume integral.

The definition of the solid specifies that every cross section taken perpendicular to the chosen axis is a square. A square has all sides equal, so the only geometric quantity available to determine its size is the width of the base measured perpendicular to the cross-sectional plane.

Because that width varies as you move along the axis, the solid’s slice size changes accordingly. The integral accumulates these varying square areas to produce the total volume.

Yes, but only if each subinterval produces well-defined square cross sections. This situation requires splitting the volume into separate integrals, one for each portion of the domain.

You must ensure that the side-length function is positive and meaningful across each interval. If the region becomes disconnected, the solid will consist of separate pieces, and the total volume is the sum of the volumes of these pieces.

The side-length function can legitimately reach zero, meaning the square cross section collapses to a point. This does not cause a problem for the integral, as the area at that point is simply zero.

Such solids often taper to a sharp end. The integral naturally accounts for this change, provided the width approaches zero continuously rather than through a discontinuity.

Small adjustments in the boundary curves change the side-length function, which in turn affects the area of each square slice. Because the area depends on the square of the side length, even modest changes can have amplified effects on the volume.

Key influences include:

• The steepness of the boundary curves.

• Where the width increases or decreases most rapidly.

• How long the solid extends along the axis of integration.

These factors determine the overall sensitivity of the volume to changes in the base.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

A solid has a base on the interval 0 ≤ x ≤ 4. Each cross section perpendicular to the x-axis is a square whose side length is given by s(x) = 3 + x.

Find the volume of the solid.

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

• 1 mark: Correct expression for the area of a cross section, A(x) = (3 + x)².

• 1 mark: Correct integral set-up, V = ∫ from 0 to 4 of (3 + x)² dx.

• 1 mark: Correct final volume, V = 124 cubic units.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

A region in the xy-plane is bounded by the curves y = 2x + 1 and y = 5 – x on the interval where they intersect. A solid is formed with this region as its base. Cross sections taken perpendicular to the x-axis are squares.

(a) Determine the x-coordinates of the intersection points of the curves.

(b) Write an integral expression for the volume of the solid.

(c) Evaluate the volume.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

• 1 mark: Correct intersection calculation: 2x + 1 = 5 – x, giving x = 4/3.

• 1 mark: Correct identification of the interval: from x = 4/3 to x = 5/3 (or correctly solving the full system if limits are stated explicitly).

• 1 mark: Correct side-length expression: difference of curves, s(x) = (5 – x) – (2x + 1) = 4 – 3x.

• 1 mark: Correct integral set-up for volume: V = ∫ from 4/3 to 5/3 of (4 – 3x)² dx.

• 1–2 marks: Correct evaluation of the integral, with 1 mark for correct expansion and integration steps, and 1 mark for correct final numerical volume.