AP Syllabus focus:

‘When cross sections are rectangles, students express height and width using given functions, form the area formula for each slice, and integrate to obtain the solid’s volume.’

Rectangular cross-sectional solids arise when a plane region serves as a base and every slice perpendicular to an axis forms a rectangle whose dimensions vary with position.

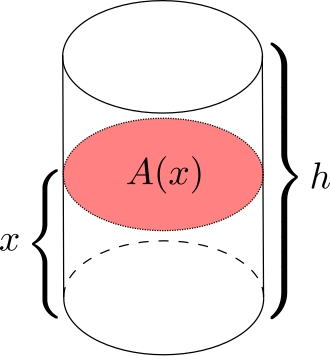

This diagram shows a cylinder with a thin slice taken at position , whose cross-sectional area is denoted . It illustrates how volume arises from integrating an area function along an axis. In rectangular cross-section problems, corresponds to a rectangle rather than a circle. Source.

Understanding Rectangular Cross Sections

A rectangular cross section is formed when a solid is built by stacking infinitely many thin rectangles perpendicular to either the x-axis or the y-axis. The key idea is that each slice has an area determined by a variable width and height, both of which depend on the position along the chosen axis of integration. This subsubtopic emphasizes how geometric attributes of the slices can be expressed using known bounding functions of the base region.

When working with such solids, AP Calculus AB students need to identify which direction the slices are taken, determine the dimensions of each rectangle, and express these dimensions as functions that can be integrated to accumulate total volume.

Base Regions and Orientation

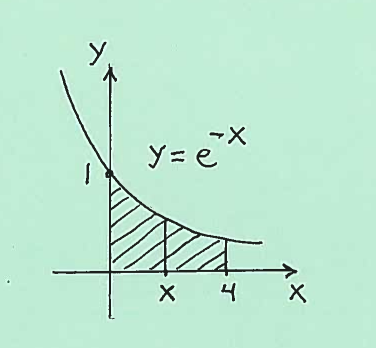

The base region of the solid is a two-dimensional area in the coordinate plane bounded by one or more curves. This base determines where rectangular slices are taken. The orientation of the slices—perpendicular to the x-axis or the y-axis—dictates both the variable of integration and how the dimensions of the rectangles are expressed.

• If slices are perpendicular to the x-axis, their width is , and their height is determined by the vertical distance between bounding curves evaluated at a given x-value.

• If slices are perpendicular to the y-axis, their width is , and their height is determined by the horizontal distance between bounding curves evaluated at a given y-value.

Before any formula is written, students must understand how the geometry of the region influences which dimensions apply to each rectangle.

Determining Rectangle Dimensions

Each rectangular slice has two dimensions: a base length (sometimes called breadth) determined by the region’s boundaries, and a height that may come from a geometric description or contextual model. These dimensions typically vary along the axis of integration.

Cross-sectional height: The dimension of a rectangle taken perpendicular to the slice width, determined by a function or expression describing the vertical or horizontal extent of the slice.

In many problems, the height is given directly as a function such as or , while the base length must be derived from the difference of two bounding functions. In other scenarios, the height may be constant or determined by contextual conditions involving the underlying geometry.

Because rectangular cross sections are highly adaptable, a problem may use any combination of functions to define the rectangle’s dimensions. What remains consistent is that both dimensions must be expressible in terms of the variable of integration.

Area of a Rectangular Slice

The area of each infinitesimally thin rectangular slice is the product of its variable height and variable base length. This must be written in the correct variable before constructing the definite integral that yields the volume.

= Area of a rectangular cross section at position

(base length and height terms described by the region’s defining functions)

The expression for or depends strictly on the geometry of the region, and students must carefully link all dimensions to the appropriate variable. A common source of error is mixing variables or using inconsistent functions; each dimension must be written exclusively in terms of x when integrating with respect to x, or exclusively in terms of y when integrating with respect to y.

After determining the expression for slice area, a student is ready to construct the volume integral. This step relies on understanding that the definite integral accumulates infinitely many rectangular slice areas to form the entire solid.

Volume as Accumulated Rectangle Areas

Rectangular cross-section problems rely on interpreting volume as accumulated area. Because a solid is built from layered rectangles, the definite integral computes the total volume by summing their areas across the domain of integration.

= Volume of the solid

= Area of each rectangular slice

= Interval across which slices are taken

This expression reinforces the view of integration as an accumulation process, consistent with other applications of integrals in the AP Calculus AB curriculum. When using , the formula is analogous, with corresponding adjustments to the rectangle dimensions and the limits of integration.

A complete setup must include:

• Clear identification of the interval over which rectangles are taken.

• Correct expressions for both rectangle dimensions based on bounding curves or context.

• A properly constructed integrand that reflects the product of base length and height.

• Integration with respect to the variable aligned with slice orientation.

Applications of Rectangular Cross Sections

Rectangular cross sections appear not only in pure geometric constructions but also in modeling contexts where physical or conceptual constraints produce variable rectangular shapes. In applied scenarios, functions may represent measurements such as widths of containers, cross-sectional profiles of beams, or changing dimensions of manufactured objects.

Common application considerations for AP students include:

• Extracting geometric dimensions from verbal descriptions and translating them into variable expressions.

• Determining whether dimensions change linearly or nonlinearly with position along the axis.

• Recognizing that all modeling assumptions must be represented in the area expression for each rectangular slice.

These applications underscore the importance of interpreting functions as representations of varying physical quantities. Understanding how rectangular cross sections capture these variations is essential for successfully constructing and evaluating volume integrals in diverse settings.

This sketch shows a solid with a base in the -plane and a vertical rectangular slice at a chosen value of . It demonstrates how a boundary curve determines the height of each slice. The original example uses square cross sections, a special case of rectangular sections. Source.

FAQ

The height of the rectangle comes from whatever the problem explicitly states. If the problem specifies a height function, you must use that even if it is unrelated to the region’s vertical extent.

If no height function is provided, the height is normally derived from how the cross section is described in relation to the base region. In such cases, height depends on the geometry of the region’s boundaries.

Base length is always a positive distance. If subtracting two boundary expressions gives a negative quantity, it means the functions were placed in the wrong order.

Simply take the absolute difference or swap the expressions so that the resulting length corresponds to the actual geometric width of the base.

Tilted cross sections fall outside the standard AP Calculus AB framework, which assumes slices perpendicular to an axis.

If a problem describes an orientation that is not perpendicular, it must still be converted into a perpendicular-slice description. This usually involves expressing the base region in the axis-aligned variable that the problem ultimately requires.

The interval of integration reflects how far the slices travel along the axis where the cross sections are taken. This interval depends solely on the projection of the base region onto that axis.

The height function influences the area of each slice but does not restrict where slices begin or end unless the problem explicitly states domain constraints.

Yes. A base length becomes piecewise when the bounding curves change dominance or when the region’s geometry shifts.

In such cases:

• Split the integral at the points where the expression for base length changes.

• Write a separate integral for each subinterval with its correct base length and height expression.

• Add all integrals to obtain the total volume.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

A solid has a base in the xy-plane bounded by the curves y = 0, y = 2, and x = 4. Cross sections perpendicular to the x-axis are rectangles whose heights are given by h(x) = x + 1.

(a) Write an expression for the area of a cross section at position x.

(b) Set up, but do not evaluate, the integral that gives the volume of the solid.

Question 1

(a) 1 mark

• Correct area expression: A(x) = (upper y bound − lower y bound) multiplied by (height).

Since the region spans y = 0 to y = 2, base length is 2.

Award the mark for A(x) = 2(x + 1).

(b) 1–2 marks

• 1 mark for correct structure of the integral: V = ∫ A(x) dx.

• 1 mark for correct limits: from x = 0 to x = 4.

Final answer: V = ∫ from 0 to 4 of 2(x + 1) dx.

Total: 2–3 marks depending on completeness.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

A region in the xy-plane is bounded by the curves y = x, y = 4, and the y-axis. A solid is formed by taking rectangular cross sections perpendicular to the y-axis. The base of each rectangle extends horizontally from the y-axis to the line x = y. The height of each rectangle is given by k(y) = 3y + 2.

(a) Write an expression for the base length of a cross section in terms of y.

(b) Write an expression for the area of a cross section at height y.

(c) Write, but do not evaluate, the definite integral that represents the volume of the solid.

(d) Explain why the limits of integration used in part (c) are appropriate.

Question 2

(a) 1 mark

• Correct base length: distance from x = 0 to x = y, so base length is y.

(b) 1 mark

• Correct area expression: A(y) = (base length)(height) = y(3y + 2).

(c) 1–2 marks

• 1 mark for writing V = ∫ A(y) dy.

• 1 mark for correct limits: from y = x-intersection at 0 to y = 4.

Final answer: V = ∫ from 0 to 4 of y(3y + 2) dy.

(d) 1–2 marks

• Justification should mention that slices are perpendicular to the y-axis, so integration is with respect to y.

• Limits are determined by the vertical boundaries of the region: y runs from 0 to 4.

Total: 4–6 marks depending on detail and accuracy.