AP Syllabus focus:

‘Migration has cultural effects on both migrants and the communities they join or leave.’

Migration reshapes cultural landscapes by transferring beliefs, practices, languages, and identities across space, influencing both migrant groups and their origin and destination societies in complex ways.

Cultural Effects of Migration

Migration generates significant cultural change, altering how communities understand identity, belonging, and social interaction. These cultural effects operate at multiple scales—from the household to global networks—and are shaped by patterns of movement, the characteristics of migrants, and the responses of receiving and sending societies.

Cultural Diffusion Through Migration

Migration is a major driver of cultural diffusion (the spread of cultural traits across space). As migrants relocate, they carry their cultural practices with them and introduce them into new environments.

Forms of Cultural Diffusion Associated With Migration

Relocation diffusion: Migrants physically move from one place to another, bringing cultural traits such as foodways, religious practices, or artistic traditions.

Stimulus diffusion: Local communities adopt an underlying cultural idea introduced by migrants but modify it to fit their cultural context.

Expansion diffusion: Cultural traits spread from migrants to the host society while remaining strong within the migrant community itself.

These forms of diffusion shape the extent to which cultural traits blend, coexist, or remain distinct across landscapes.

Identity, Belonging, and Cultural Interaction

Migrant Identities in New Contexts

Migrants frequently navigate bicultural identities, maintaining ties to their culture of origin while adapting to the cultural norms of the destination. This process often produces:

Acculturation, defined as the process by which migrants adopt some cultural traits of the host society while retaining aspects of their original culture.

Acculturation: The process through which individuals or groups adjust to a new culture by adopting certain traits while maintaining elements of their original cultural identity.

Acculturation varies depending on migrant generation, community support, and the cultural attitudes of the host society.

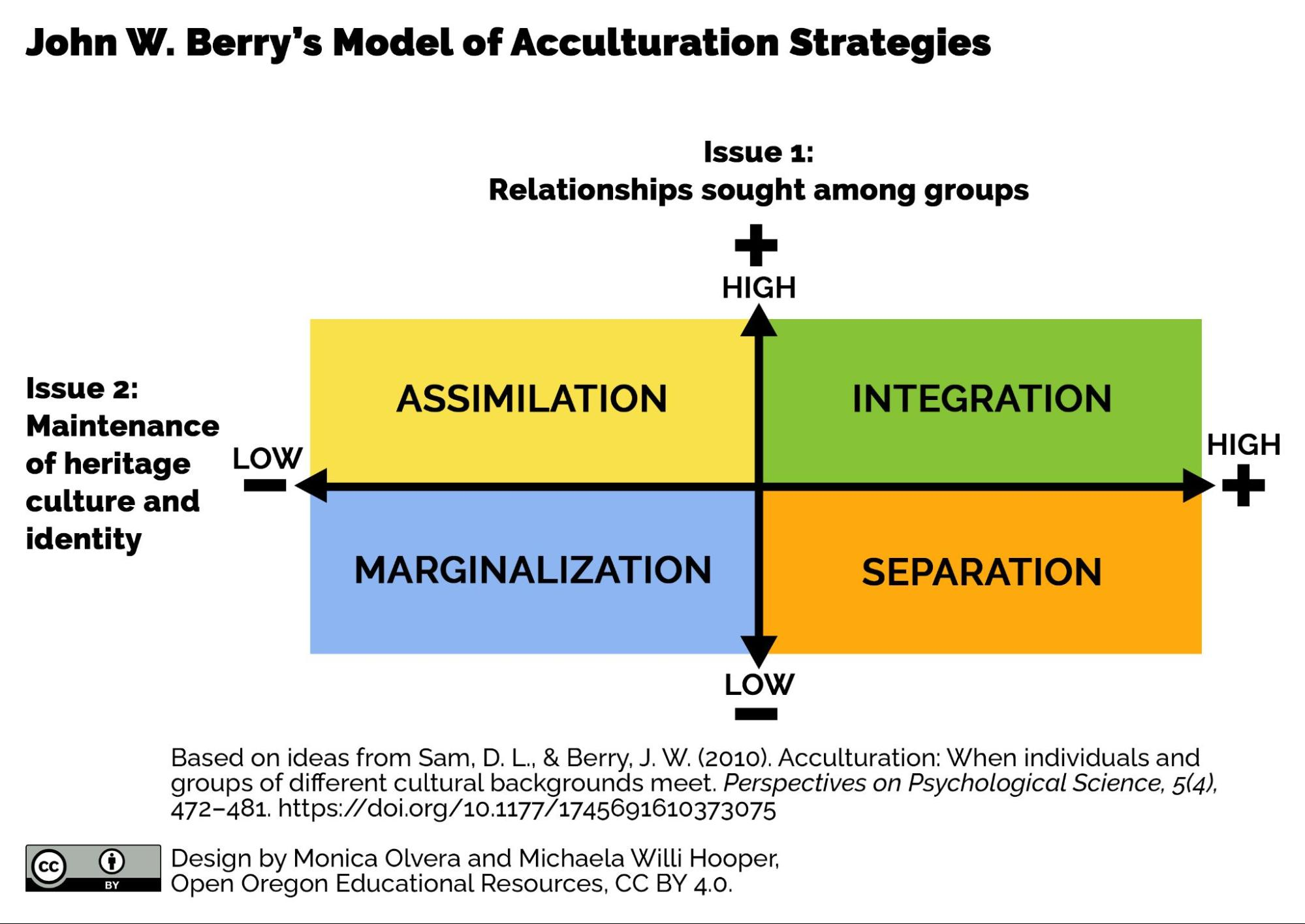

This chart shows Berry’s four acculturation strategies—integration, assimilation, separation, and marginalization—arranged along two axes indicating orientation toward the host and heritage cultures. It visualizes how migrants negotiate cultural identity within destination societies. The original source adds brief notes about adaptation beyond AP scope, but the core model directly supports concepts of acculturation described in the study notes. Source.

Migrants also contribute to cultural hybridity—the blending of cultural traits from multiple sources to form new cultural expressions, such as fusion cuisine, hybrid musical styles, or bilingual communication patterns.

Cultural Interaction With Host Communities

Receiving societies respond to new cultural influences in diverse ways. Cultural interactions may produce:

Syncretism, as cultural traits blend into new, combined forms.

Multiculturalism, as societies embrace cultural diversity and actively support coexistence.

Tension or conflict, when cultural differences become politicized or when rapid cultural change sparks backlash.

These responses influence how cultural landscapes evolve and how migrants experience inclusion or exclusion.

Impacts on Cultural Landscapes

Migration alters the cultural landscape—the visible imprint of human activity on the environment. Cultural effects include:

Introduction of new religious buildings, such as temples, mosques, or churches.

Development of ethnic neighborhoods that serve as cultural hubs.

Diffusion of food establishments, festivals, and artistic styles.

Increased use of multilingual signage and services.

These visible changes reflect deeper cultural transformations occurring within the community.

This photograph depicts a Hispanic/Latino ethnic enclave in the Fruitvale district of Oakland, California, featuring Spanish-language signs and cultural motifs. It illustrates how migrant communities imprint their cultural heritage onto the built environment through businesses, symbols, and public spaces. The source includes references to Día de los Muertos that extend slightly beyond AP content but reinforce the concept of distinct cultural landscapes shaped by migration. Source.

Language and Migration

Language is a powerful marker of cultural identity, and migration strongly influences linguistic patterns.

Language Maintenance and Shift

Migrants may maintain their heritage languages within households or community spaces, while adopting the dominant language for school, work, or public life. Over generations, this may lead to:

Bilingualism, as individuals navigate multiple linguistic environments.

Language shift, when later generations gradually stop using the heritage language in favor of the dominant language.

Language practices provide insight into cultural assimilation, preservation, and the long-term impacts of migration on identity.

Religion and Migration

Migrants often bring religious traditions that reshape the spiritual landscape of the destination region. Religious effects include:

Establishment of new places of worship.

Growth of diverse religious communities.

Introduction of new rituals, festivals, and moral frameworks.

Religious diversity can enrich local culture or generate cultural debate, depending on community attitudes and political contexts.

Cultural Effects on Sending (Origin) Regions

Migration also impacts the cultural patterns of the communities migrants leave behind. These effects include:

Cultural remittances, meaning migrants transmit cultural ideas, values, and practices—such as democratic norms, fashion trends, or new social expectations—back to their origin communities.

Shifts in local traditions as younger migrants leave and older residents maintain customs.

Influence of transnationalism, as migrants sustain cultural, economic, and social connections across borders.

Sending regions may experience cultural change even without physical return migration.

Migration, Globalization, and Cultural Change

Migration contributes to cultural globalization by connecting distant regions and accelerating exchanges of cultural traits. This process increases cultural interdependence and fosters global cultural flows, such as:

Worldwide adoption of foods, music, or media.

Growth of diasporic networks that maintain cultural ties.

Spread of cultural norms related to gender roles, family structure, and social behavior.

These global linkages highlight migration as a key force shaping cultural landscapes across the world.

FAQ

Cultural enclaves can strengthen cohesion within migrant communities by offering shared institutions, such as shops, faith centres, and community organisations.

However, their impact on wider urban cohesion depends on levels of interaction between groups. In some cities, enclaves become important bridges by facilitating intercultural contact; in others, limited interaction may reinforce social separation.

Heritage language retention depends on several influences:

Presence of community institutions such as cultural schools or religious centres

Availability of media in the heritage language

Family attitudes toward bilingualism

Local policies on language learning and multilingual support

Stronger community networks typically lead to higher rates of intergenerational language transmission.

Migrants frequently introduce new cuisines, ingredients, and preparation methods, which may gradually be adopted by local residents.

Food-related change is especially visible in urban areas where diverse communities interact closely. Over time, fusion cuisines may emerge as cultural elements blend, normalising the presence of formerly unfamiliar dishes in mainstream diets.

Return migrants often bring back new ideas about work, gender roles, education, and lifestyle choices gathered from their destination regions.

Their influence can accelerate social change by introducing alternative norms that challenge long-standing expectations. Communities with high levels of out-migration tend to experience faster diffusion of such cultural remittances.

Host society responses are shaped by:

Historical experiences with migration

Government policies on integration or assimilation

Economic conditions influencing perceptions of competition

Media narratives about migrant groups

Positive framing and inclusive policies tend to support multicultural acceptance, while political tension or economic insecurity can fuel resistance to cultural diversity.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way migration can lead to the formation of ethnic enclaves in destination regions.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying a valid cultural process (e.g., migrants clustering to maintain cultural practices).

1 mark for explaining how shared language, religion, or traditions encourage spatial concentration.

1 mark for linking this concentration to the development of distinct ethnic neighbourhoods or cultural landscapes.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Assess how migration can simultaneously preserve cultural identity and promote cultural change within host societies.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for describing how migrant communities preserve cultural identity (e.g., maintaining language, religion, or cultural traditions).

1 mark for explaining the role of acculturation or bicultural identity.

1 mark for explaining how migrant cultural traits diffuse into host societies (e.g., food, festivals, places of worship).

1 mark for discussing cultural hybridity or syncretism.

1–2 marks for evaluative comments such as variation across communities, generational differences, or differing levels of host acceptance.