AP Syllabus focus:

‘Critiques of Malthusian theory are used to evaluate population change and its consequences in different contexts.’

Critiques of Malthusian theory highlight alternative explanations for population growth, resource availability, and human innovation, offering students a nuanced understanding of how population dynamics function across diverse global contexts.

Major Critiques of Malthusian Theory

Malthus argued that population grows exponentially while food supply grows linearly, inevitably causing shortages. Critics challenge the accuracy and universality of this model, focusing on technological innovation, demographic change, and socio-economic variability across regions.

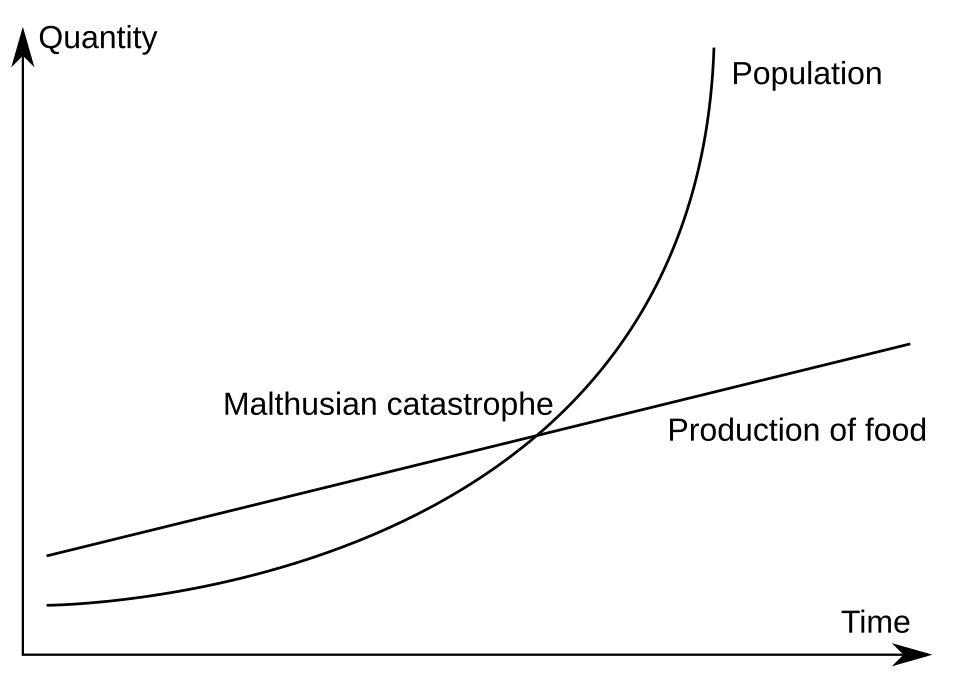

Malthus argued that population grows geometrically (exponentially) while food supply increases arithmetically (linearly).

This diagram shows Malthus’s original model, with population increasing exponentially while food production rises only in a straight, linear trend. The point where the population curve rises above the food line represents the Malthusian catastrophe, when the population outstrips available resources. This visual helps students see why critics question whether real-world societies actually follow this simple, pessimistic pattern. Source.

Technological Optimism and Innovation

One of the most influential critiques emphasizes the role of human ingenuity, arguing that people can expand resource availability through innovation rather than being constrained by fixed limits.

Technological Optimism: The belief that scientific, agricultural, and industrial innovation can expand resource supplies faster than population growth increases demand.

Innovations such as synthetic fertilizers, mechanized farming, genetically modified crops, and enhanced irrigation systems have significantly increased agricultural productivity, contradicting the assumption of linear food growth. Many critics argue that Malthus underestimated humanity’s adaptive capacity, noting that food production has outpaced population growth in numerous world regions. This perspective aligns closely with the ideas of Ester Boserup, who argued that population pressure stimulates agricultural innovation.

The Boserupian Counterargument

The Boserupian perspective asserts that rising population density encourages societies to adopt more efficient, intensive agricultural practices. This approach challenges the notion that population growth is inherently problematic.

Intensification: A shift toward more labor- or technology-intensive forms of agriculture to increase productivity per unit of land.

Boserup’s critique reframes population growth as a driver of progress rather than a threat to resource stability. She contended that societies historically increased production through improved tools, new crop varieties, and better land management as population pressures rose. This interpretation directly contrasts with Malthus’s prediction of unavoidable crises.

Demographic Transition as a Rebuttal

Demographers argue that Malthus did not anticipate declining fertility rates in industrializing societies. As nations move through stages of socioeconomic development, fertility and mortality shift toward lower levels, reducing long-term pressures on resources.

Key reasons critics point to demographic change include:

Increased urbanization, which lowers average family size.

Expanded women’s education, decreasing fertility rates.

Improved health care, reducing reliance on large families.

Rising economic development, shifting labor needs.

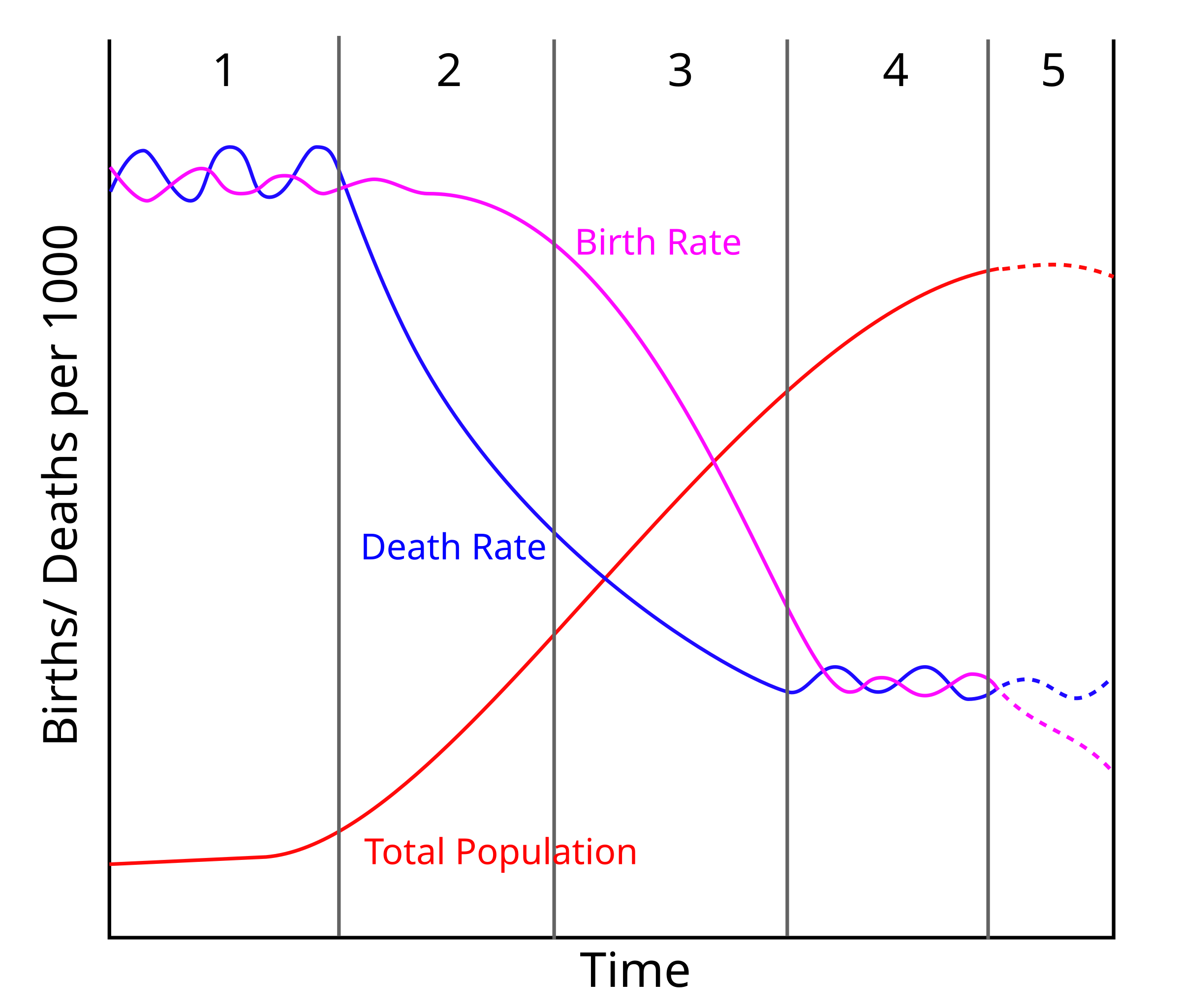

The demographic transition model shows how, over time, declining birth and death rates can slow population growth without the universal, catastrophic famines Malthus anticipated.

This diagram shows the demographic transition model, with separate curves for birth rate and death rate across stages 1 through 5. As societies industrialize and develop, both rates fall, and population growth eventually slows and can approach zero or decline. The inclusion of a Stage 5 goes slightly beyond the classic four-stage model but effectively illustrates why modern demographic patterns challenge Malthus’s continuous-growth assumptions. Source.

Uneven Distribution, Not Absolute Scarcity

Another major critique contends that problems attributed to resource scarcity often stem from unequal distribution, political conflict, or economic barriers, not absolute shortages. Critics argue that famine and hunger frequently occur even when adequate food exists globally.

Important considerations include:

Political instability disrupting food transport.

Economic inequality limiting access to food.

Global trade patterns concentrating resources in wealthier nations.

Land ownership systems restricting production or distribution.

These factors suggest that resource crises are shaped more by human systems than by natural limits, contradicting the universal applicability of Malthusian predictions.

Environmental Critiques and Neo-Malthusian Perspectives

While many critiques challenge Malthus, some modern theorists—often labeled neo-Malthusians—refine his ideas rather than reject them, focusing on environmental degradation and long-term sustainability. However, even neo-Malthusians face criticism from environmental geographers who argue that resource scarcity must be evaluated through complex human-environment interactions rather than simple population counts.

Critics of neo-Malthusian thinking highlight factors such as:

Technological adaptation reducing ecological strain.

Improved conservation policies and sustainable practices.

Transition to renewable energy moderating resource pressure.

Environmental regulation mitigating depletion.

These critiques maintain that environmental limits are real but can be managed through thoughtful planning rather than seeing population as the sole driver of decline.

Cultural, Economic, and Political Variability

Critiques also emphasize that Malthusian theory fails to account for differences among regions, cultures, and political systems. Population dynamics vary significantly across space, and Malthus’s model assumes uniform behavior.

Key points include:

Cultural norms influencing family size differently in each society.

Government policies shaping fertility, such as pronatalist and antinatalist programs.

Economic structures determining whether large families are beneficial or burdensome.

Migration flows redistributing population and resource demand between regions.

These factors reveal that population growth is not solely driven by biological reproduction but by multidimensional influences that Malthus did not consider.

Critiques Centered on Modern Globalization

Globalization further undermines Malthusian assumptions by enabling widespread trade, resource substitution, and knowledge diffusion. Critics argue that today’s interdependent world reduces the likelihood of isolated resource shortages.

Important globalization-based critiques include:

Nations can import food, reducing reliance on local production.

Global supply chains move resources from surplus to deficit areas.

International aid can prevent famine during crises.

Shared technologies accelerate agricultural modernization across borders.

These dynamics demonstrate that contemporary populations operate in a global system unlike the isolated agrarian societies Malthus studied, making his predictions less relevant for evaluating modern population change and its consequences across different contexts.

FAQ

Neo-Malthusians agree that population growth can strain resources but place stronger emphasis on environmental degradation, climate change, and long-term ecological sustainability.

They argue that even with technological improvements, overconsumption, pollution, and biodiversity loss can overwhelm ecosystems.

Unlike Malthus, they typically support policy interventions such as conservation measures, family planning, and sustainable development strategies.

Critics note that Malthus assumed countries relied mainly on local production, but modern economies can import food to meet shortages.

Global trade reduces vulnerability by allowing regions with limited agricultural capacity to rely on international markets.

This interconnected system weakens the idea that local population growth must always outpace local food supply.

Political stability helps ensure the flow of food, investment in agriculture, and fair distribution, reducing the likelihood of scarcity.

In contrast, conflict, corruption, and weak governance can create famine-like conditions even when food is available.

This suggests that political context is often more decisive than population growth in determining resource outcomes.

Economic inequality affects access to food far more than total supply.

Key mechanisms include:

• Unequal purchasing power preventing poorer households from buying available food

• Land ownership patterns limiting production or access

• Market systems directing food supply towards wealthier consumers and countries

These dynamics mean scarcity may be socially produced rather than a result of population pressure.

While innovation has expanded food production, some geographers argue it creates new forms of environmental strain, such as soil depletion, water scarcity, and reliance on energy-intensive inputs.

They also highlight that technological gains are unevenly distributed, benefiting some regions far more than others.

This suggests that innovation mitigates but does not entirely remove long-term sustainability challenges.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which technological innovation serves as a critique of Malthusian theory.

Mark scheme

• 1 mark for identifying that technological innovation increases food production or resource availability.

• 1 mark for explaining how innovations such as fertilisers, mechanisation, or improved crop varieties expand carrying capacity.

• 1 mark for linking this directly to why Malthus’s prediction of inevitable shortages may not occur.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Assess two criticisms of Malthusian theory that highlight why his predictions may not accurately describe contemporary population trends.

Mark scheme

• 1 mark for identifying a valid criticism (e.g., demographic transition, unequal distribution, Boserupian innovation, political/economic factors).

• 1 mark for explaining how the first criticism challenges Malthus’s assumptions.

• 1 mark for applying the first criticism to contemporary or global population trends.

• 1 mark for identifying a second valid criticism.

• 1 mark for explaining how the second criticism challenges Malthus’s assumptions.

• 1 mark for applying the second criticism to contemporary or global population trends.