AP Syllabus focus:

‘Factors leading to devolution include the division of groups by physical geography; explain how mountains, deserts, or distance can encourage regional autonomy.’

Physical geography shapes political outcomes by separating populations, limiting interaction, and encouraging distinct regional identities, often resulting in demands for autonomy, self-rule, or full political separation.

Physical Geography as a Driver of Devolution

Physical geography plays a critical role in shaping how groups interact, govern, and differentiate themselves from one another. When natural features divide populations, the reduced contact and increased isolation can foster unique cultural, linguistic, or economic traits. These differences become politically significant when regions feel that central governments fail to represent their interests, thus fueling devolution, the process in which power shifts downward from a central authority to regional units.

How Natural Barriers Divide Groups

Physical features such as mountains, deserts, and large distances limit movement and communication, creating fragmented political landscapes. These divisions can weaken a state's internal cohesion and amplify calls for regional authority.

Devolution: The transfer or delegation of power from a central government to regional or local governments.

Separated regions often develop localized governance systems, which may eventually formalize into autonomous administrative structures. These patterns directly support the syllabus emphasis on how physical geography contributes to autonomy movements.

Mountains as Political Dividers

Mountain ranges are among the most powerful geographic forces shaping political behavior. They restrict travel, hinder state control, and often allow culturally distinct groups to develop in relative isolation.

Mountains encourage devolution in several ways:

They form transportation barriers, slowing the spread of national policies.

They support cultural divergence, as isolated populations maintain unique languages, religions, or social norms.

They create security challenges, making it difficult for states to administer or police mountainous borderlands.

They enable regional solidarity, as highland communities often depend on each other more than on lowland national governments.

Regions divided by mountains may therefore push for self-governance when national political systems fail to match their local needs or identities.

Deserts as Isolating Landscapes

Deserts create vast uninhabitable or sparsely populated areas that act as political buffers between regions. Their harsh conditions reduce the feasibility of centralized oversight and transport infrastructure.

Deserts shape devolution by:

Limiting economic integration, as desert regions may rely on pastoralism or resource extraction rather than national economic patterns.

Reinforcing cultural distinctiveness, since isolated desert groups often develop specialized survival strategies and mobility patterns.

Creating administrative gaps, where central governments struggle to deliver services or maintain consistent political presence.

Autonomy: A degree of self-governance granted to a region within a state, allowing local decision-making on certain political or cultural matters.

These desert-driven dynamics highlight how residents might feel disconnected from national institutions, increasing support for devolved powers.

This map depicts the Sahara Desert and its surrounding transition zones, illustrating how a vast arid region limits movement and interaction between northern and sub-Saharan populations. The visual shows how an expansive desert can produce political and cultural separation that encourages regional autonomy. The inclusion of the Sahel and broader sub-Saharan area goes slightly beyond the syllabus but reinforces how desert barriers shape regional divisions. Source.

Distance and Spatial Separation

Even without dramatic physical barriers, long distances alone can weaken political unity. Remote regions often face slower communication, limited representation, and diminished economic ties with the national core.

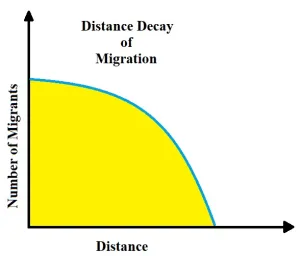

This graph illustrates the concept of distance decay, showing how interaction decreases as distance increases. Although presented in the context of migration, the underlying relationship helps explain why remote regions experience weakened ties with central governments, supporting demands for autonomy. The figure includes migration-specific wording that exceeds syllabus content, but the geographic principle applies directly to political separation. Source.

Distance contributes to devolution by:

Increasing governance inefficiencies, prompting remote populations to prefer local administration.

Reducing political trust, as people far from capital cities may feel ignored or marginalized.

Encouraging regional identity, especially when distance correlates with distinct environmental zones and lifestyles.

Hindering integration projects, such as national infrastructure or education standardization.

A distant region may gradually evolve a political outlook different from the national majority, creating fertile ground for autonomy movements.

Cultural, Political, and Economic Implications

Physical separation often produces tangible differences in identity and behavior. Over time, these differences create pressures that can challenge or reshape the political structure of the state.

Key implications include:

Cultural divergence: Isolated groups may develop languages, traditions, or belief systems distinct from the national culture.

Economic specialization: Geographic conditions may produce regional economies misaligned with national priorities.

Political alienation: Groups may perceive national policies as irrelevant, unjust, or insufficiently responsive.

Demands for self-determination: People may seek the right to control political decisions affecting their unique circumstances.

Self-determination: The principle that groups have the right to determine their political status and pursue economic, cultural, or social development.

As physical geography reinforces these regional differences, the push for devolved governance can intensify, directly aligning with the AP focus on explaining how natural features encourage autonomy.

Physical Geography and the Persistence of Regional Autonomy

Once autonomy emerges in geographically divided regions, physical landscapes often help maintain it. Natural barriers can protect regional institutions, limit state intervention, and sustain cultural continuity. These conditions show how mountains, deserts, and distance not only encourage devolution but also help entrench it over time, shaping long-term political patterns.

FAQ

Physical geography shapes daily life by affecting settlement patterns, resource use, and modes of transport. Over generations, these factors embed distinct cultural practices and social norms within isolated regions.

Mountain communities, desert groups, or populations separated by long distances often maintain unique traditions because they interact less frequently with national cultural centres.

This persistent distinctiveness forms the basis for long-term regional identities that later feed into autonomy movements.

Governments face logistical and financial constraints when attempting to govern remote areas. Difficult terrain increases the cost of infrastructure, service delivery, and administrative presence.

Isolated regions may also resist integration if national policies conflict with local livelihoods or cultural patterns.

These ongoing challenges make it harder for states to maintain strong political and economic ties with separated populations.

Successful integration often relies on a combination of large-scale transport and communication projects:

• Roads and tunnels that connect mountain valleys

• Rail corridors that bypass deserts or traverse sparsely populated zones

• Digital infrastructure enabling remote access to government services

However, high costs and political resistance sometimes limit the feasibility of these solutions.

Regional economies shaped by distinct physical environments may diverge from national economic priorities. For example, desert regions may depend on pastoralism or mineral extraction, while mountain communities may rely on tourism or subsistence farming.

When national policies fail to support these specialised economies, isolated groups may push for local control over taxation, land use, and resource management, strengthening demands for autonomy.

Yes, although digital connectivity reduces some obstacles, physical geography continues to influence economic opportunities, transport flows, and political access.

Technology can help remote communities communicate with the state, but it cannot fully overcome limited physical mobility, uneven public investment, or cultural distinctiveness rooted in place.

As a result, physical barriers still play a meaningful role in sustaining devolutionary pressures.

Practice Questions

(1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which a physical geographic barrier can contribute to devolution within a state.

(1–3 marks)

• 1 mark for identifying a relevant physical barrier (e.g., mountains, deserts, large distances).

• 1 mark for explaining how the barrier reduces interaction, communication, or state control.

• 1 mark for linking this reduced interaction to increased support for regional autonomy or self-governance.

(4–6 marks)

Using specific geographic reasoning, analyse how mountains, deserts, and distance can separately and collectively encourage regional autonomy within a multi-ethnic state.

(4–6 marks)

Award marks based on the following criteria:

• 1–2 marks: Describes at least one physical feature (mountains, deserts, or distance) and its isolating effect.

• 3–4 marks: Provides clear explanation of how different physical features create separate cultural, economic, or political identities that encourage autonomy.

• 5–6 marks: Offers a well-developed analysis showing how multiple physical features can work together to intensify devolutionary pressures, with explicit reference to reduced integration, limited state reach, or reinforced regional identity.