AP Syllabus focus:

‘Factors leading to devolution include terrorism, economic and social problems, and irredentism; explain how insecurity, inequality, or border claims can weaken state unity.’

States face pressures that undermine unity, and terrorism, economic and social problems, and irredentism each generate conditions that encourage fragmentation, weaken authority, and promote demands for autonomy or separation.

Factors Contributing to Devolution

Terrorism as a Catalyst for Devolution

Terrorism is politically motivated violence aimed at civilians or symbolic targets to create fear and achieve ideological goals. When terrorist activity concentrates within a particular region, it can fuel devolutionary pressures by highlighting a perceived disconnect between the central government and local populations.

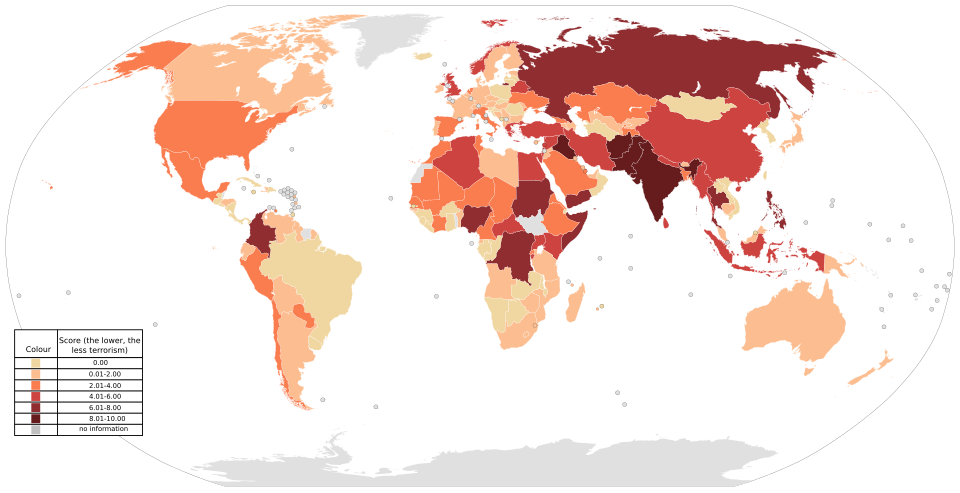

This map shows the Global Terrorism Index scores by country, with darker shades indicating higher levels of terrorism. It helps students see that terrorism is not evenly distributed, but clustered in specific regions where political grievances and weak governance are often acute. The map includes more countries than those mentioned in the syllabus, but its global overview reinforces how spatial patterns of terrorism can intensify regional demands for autonomy or political change. Source.

Terrorism: The use or threat of violence by nonstate actors to advance political aims by generating fear and instability.

Terrorist movements often emerge in areas experiencing political marginalization, economic exclusion, or cultural repression. Regional populations may feel that the central state is either unable or unwilling to provide security, increasing support for autonomy. Major processes include:

• Security vacuum formation — localized instability allows insurgent groups to strengthen territorial influence.

• Identity-based mobilization — violence amplifies ethnic, religious, or national identities and encourages separatist narratives.

• Erosion of state legitimacy — persistent attacks undermine trust in national governments.

Terrorism can shift political bargaining power. Governments may grant limited autonomy to calm unrest, or regions may intensify independence demands. These shifts create long-term spatial consequences, including altered administrative boundaries or newly devolved regions.

Economic and Social Problems and Devolutionary Pressure

Economic and social problems shape political cohesion by affecting perceptions of inclusion, fairness, and opportunity. Uneven development, lack of infrastructure, persistent poverty, and unequal access to public services can provoke grievances.

Economic inequality refers to uneven distribution of wealth or opportunity across regions. When one region experiences chronic underinvestment, resentment toward central authorities intensifies. This may lead populations to argue that local control of resources would yield better outcomes.

Economic Inequality: A condition in which economic opportunities, incomes, and development levels are unevenly distributed across populations or regions.

A normal sentence appears here to maintain spacing before any following definition.

Social Problems: Conditions such as poverty, unemployment, or discrimination that reduce quality of life and drive political dissatisfaction.

Economic and social instability can weaken national unity by fostering the belief that governance should be reorganized to better match regional needs. In federal states, this may manifest as demands for expanded regional authority. In unitary states, it may produce calls for decentralization or administrative restructuring.

Irredentism and Border-Based Claims

Irredentism involves political claims made by a state or ethnic group to territory controlled by another state, based on historical, cultural, or ethnic ties. These claims often overlap with contested borders and populations divided by international boundaries.

Irredentism: The political desire to unite people or territories that share cultural or historical ties but are separated by existing state borders.

Irredentism becomes a devolutionary factor when minority groups identify more strongly with populations across the border than with the state in which they currently reside.

This map shows Kurdish-inhabited areas (in green) spread across several states in Southwest Asia. It illustrates how a single cultural group can be partitioned by international borders, creating a classic setting for irredentist claims and demands for autonomy or even a separate state. The map includes geographic detail beyond the AP syllabus, but its central message—showing the mismatch between cultural geography and state borders—is essential for understanding how irredentism drives devolutionary pressure. Source.

These claims produce specific effects:

• Cross-border solidarity — ethnic groups coordinate or advocate for reunification with a neighboring state.

• Weakening of national loyalty — populations may question the legitimacy of the current state’s territorial authority.

• Territorial disputes — competing claims destabilize border regions and encourage separatist sentiment.

Irredentist tensions commonly appear where borders were drawn through colonial partitioning, geopolitical bargaining, or conflict settlements that ignored cultural geography. As states respond with military, political, or diplomatic strategies, the affected region may experience heightened nationalism or intensified fragmentation pressures.

How These Factors Undermine State Unity

Insecurity and Territorial Fragmentation

Terrorism amplifies insecurity and reduces trust in central institutions, while economic disparities create geographic patterns of discontent. Both conditions produce regions where alternative political visions take root, including separatism or demands for devolved power. Irredentism adds a cross-border dimension, contributing to territorial instability and contested sovereignty.

Mobilization of Regional and Ethnic Identities

Each factor strengthens centrifugal forces, which pull a state apart by elevating subnational identities above national ones. Key pathways include:

• Cultural reinforcement — heightened awareness of shared heritage motivates collective political action.

• Territorial identification — populations view their land as culturally distinct or misaligned with state authority.

• Political organization — social movements, militias, or political parties mobilize around calls for autonomy.

Impact on Political Boundaries and Governance

As these pressures increase, states may experience:

• Administrative decentralization or the creation of autonomous regions

• Boundary adjustments to accommodate cultural or territorial claims

• Governance restructuring to address inequality or unrest

• In extreme cases, full territorial disintegration

These processes reflect the AP focus on how terrorism, social and economic disparities, and irredentist claims each contribute to devolution by weakening national cohesion and enabling alternative forms of territorial organization.

FAQ

Terrorism can strengthen regional identity by creating a shared sense of threat, sacrifice, or resistance within a specific area. Populations living in affected regions often feel that the central government does not adequately understand or protect their local conditions.

This can lead people to increasingly view themselves as a distinct community capable of governing independently. As identity solidifies, political actors may frame autonomy or separation as the only viable solution to long-term insecurity.

Economic grievances that drive devolution typically involve long-term structural inequalities, including:

• Persistent underinvestment in infrastructure

• Limited access to employment or education

• Perceived unfair taxation or redistribution

• Resource extraction without local benefit

These conditions create an environment in which regional leaders can mobilise populations by arguing that local governance would manage resources or development more fairly than the central government.

Symbolic claims emerge when cultural or historic ties exist but geopolitical conditions make territorial change unlikely. In such cases, irredentism serves mainly as a rhetorical tool for identity building.

Claims escalate into active movements when ethnic populations are concentrated, experience political marginalisation, or receive support—material or ideological—from across the border. International weakness or instability can further open opportunities for groups to push their claims more aggressively.

Governments often use a combination of political, cultural, and economic strategies to reduce irredentist tensions:

• Granting limited cultural or linguistic rights

• Expanding regional political autonomy

• Directing targeted economic investment

• Encouraging cross-border cooperation through treaties or economic zones

These measures aim to improve local satisfaction and reduce incentives for separatist alignment while keeping existing borders intact.

Migration can reshape the demographic and political landscape of regions already experiencing strain. When people flee terrorism or economic hardship, their movement can intensify labour shortages, alter identity dynamics, or create perceptions of demographic imbalance.

Receiving regions may feel pressure on services, while sending regions can lose skilled workers, compounding grievances. Both effects can feed arguments for autonomy as local leaders attempt to retain control over migration policy, development, or security.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain how terrorism can act as a devolutionary force within a state.

Mark scheme:

• 1 mark for identifying terrorism as creating instability, fear, or insecurity.

• 1 mark for stating that terrorism can weaken public trust in the central government or highlight perceived neglect of specific regions.

• 1 mark for explaining that affected regions may demand greater autonomy or political control as a response to insecurity.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Using examples, analyse how economic inequalities and irredentism can contribute to the weakening of state unity.

Mark scheme:

• 1 mark for defining economic inequality or describing uneven development.

• 1 mark for explaining how economic disparities generate regional resentment or demands for autonomy.

• 1 mark for defining irredentism or describing claims based on cross-border ethnic or cultural ties.

• 1 mark for explaining how irredentism can cause minority groups to identify more with populations in neighbouring states than with their own, weakening national cohesion.

• 1–2 marks for effective use of relevant examples (e.g., Kurdish regions, marginalised economic regions) and clear analysis connecting these factors to the fragmentation or weakening of state unity.