AP Syllabus focus:

‘Devolution occurs when states fragment into autonomous regions or subnational political-territorial units, or when states disintegrate, as in Sudan or the former Soviet Union.’

Devolution through fragmentation occurs when centralized authority weakens and regions gain autonomy or break away entirely, reshaping political space and altering how states manage identity, power, and governance.

Devolution Through Fragmentation and Disintegration

Devolution refers to the transfer of political power from a central government to regional or local units, often in response to cultural, economic, or political pressures. When these pressures intensify, states may fragment—creating new autonomous regions—or disintegrate, breaking apart into multiple independent states. These processes reshape sovereignty, territorial organization, and political stability.

Understanding Devolution in a Political Geography Context

Devolution in AP Human Geography focuses on the spatial distribution of power and how internal divisions alter the world political map. The weakening of central authority can produce a wide range of outcomes, from increased regional autonomy to complete state dissolution. These shifts highlight how territoriality, identity, and governance structures interact and conflict within states.

When a state fragments, it experiences profound challenges relating to national identity, resource control, and border formation. Such processes also reveal the importance of political negotiation and the potential for conflict when regions seek self-rule.

Core Processes in Fragmentation and Disintegration

Decentralization of authority as political power is redistributed from the central state to regional governments.

Rise of regional identity when cultural, linguistic, or ethnic groups seek greater recognition and autonomy.

Weakening of central cohesion caused by economic inequality, uneven development, or governance failures.

Formation of new borders as regions become autonomous or independent states.

Potential for conflict when competing claims emerge over territory, resources, or political legitimacy.

These processes demonstrate how internal political dynamics generate new patterns on the political map and fuel geopolitical change.

Nations, Identity, and the Push Toward Fragmentation

Groups within a state often mobilize around a shared identity, seeking increased political control over their territory. When these groups feel marginalized or underrepresented, demands for autonomy increase. In some cases, these demands lead only to internal restructuring; in others, they accelerate full state disintegration.

Autonomous Region: A subnational territory with some degree of self-governance, granted authority over internal affairs while remaining part of a larger sovereign state.

Autonomous regions emerge when the central government attempts to satisfy regional demands without permitting complete independence. This approach may stabilize a state, or it may become a stepping stone toward separation.

Fragmentation: The Creation of Autonomous Political-Territorial Units

Fragmentation occurs when internal divisions lead regions to govern themselves more independently. This form of devolution produces:

New internal political boundaries within a state

Shifted administrative hierarchies

Greater regional policymaking authority

Diverse governance models coexisting within one sovereign state

These autonomous political-territorial units may develop unique cultural, economic, or legal systems that differ from the national framework. Fragmentation does not eliminate sovereignty but reshapes how it is exercised.

One sentence to buffer definition blocks.

Subnational Political-Territorial Unit: A region within a state that possesses administrative or political authority below the national level, such as provinces or autonomous communities.

Disintegration: The Breakdown of State Sovereignty

Disintegration represents the extreme end of devolution, in which a state fully breaks apart into multiple independent states. This occurs when the central government can no longer maintain territorial integrity or manage internal conflict. Disintegration often results in:

Secession movements achieving independence

Redrawing international borders

Emergence of newly sovereign states

Geopolitical instability during transition periods

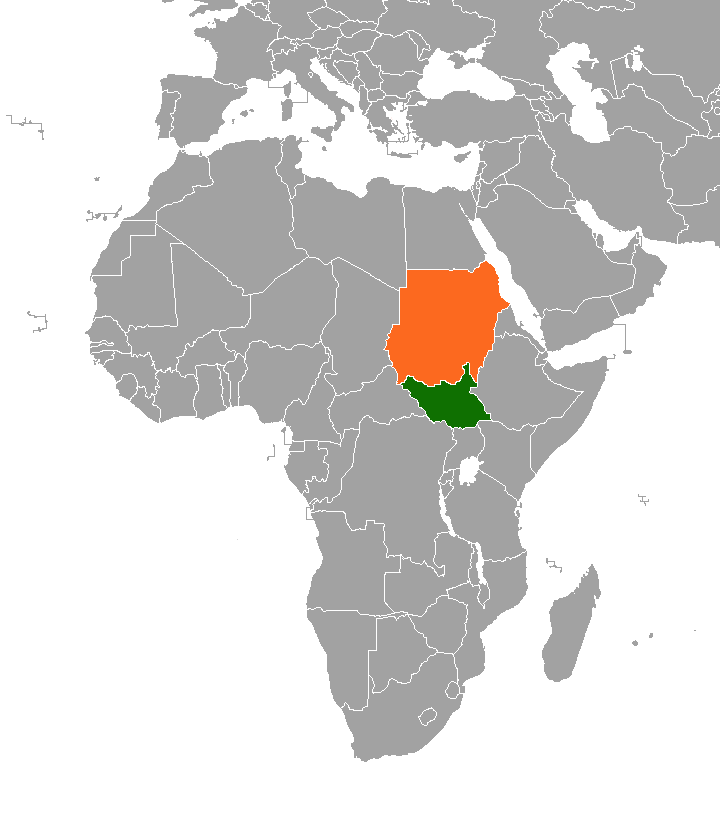

The AP syllabus highlights Sudan and the former Soviet Union as examples of disintegration. South Sudan gained independence in 2011 following prolonged conflict and regional inequality.

Map showing Sudan (orange) and South Sudan (green), highlighting the international boundary that emerged after South Sudan’s independence in 2011. This spatially represents how internal conflict and uneven power-sharing led to the disintegration of a single state into two separate sovereign countries. The map also includes some geographic detail beyond the AP Human Geography specification but provides helpful spatial context. Source.

Similarly, the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991 produced 15 independent countries, reshaping political boundaries across Eurasia.

Map of the Soviet Union showing its constituent Soviet Socialist Republics, each labeled as a distinct territorial unit. This illustrates how internal administrative divisions formed the basis for new international borders when the USSR disintegrated in 1991. The image contains extra geographic labels beyond the AP specification, but these help clarify the spatial transformation caused by disintegration. Source.

Forces Driving Fragmentation and Disintegration

Multiple factors encourage devolutionary pressures within a state:

Ethnic divisions that challenge national unity

Economic disparities between regions

Political marginalization of minority groups

Geographic barriers that isolate populations

Historical grievances that erode trust in central authority

External influence or support for separatist movements

These forces weaken the central government’s legitimacy and fuel demands for self-determination.

Spatial Outcomes of Devolution

Devolution reshapes spatial organization in several ways:

Uneven regional development as autonomous areas control their own resources

Shifts in administrative boundaries reflecting new internal divisions

Changing patterns of governance with local institutions gaining prominence

Variation in cultural expression across newly empowered regions

Potential emergence of new international borders if disintegration occurs

The resulting political landscape reflects the dynamic relationship between identity, territory, and power.

Devolution in the Contemporary World

Modern examples of devolution illustrate its ongoing relevance to political geography. States experiencing fragmentation or disintegration reveal how internal pressures can quickly alter political systems. These transformations highlight the importance of understanding devolution not only as a political process but also as a spatial one, shaping interactions between people, territories, and governing institutions.

FAQ

Early warning signs usually appear as long-term pressures rather than sudden events. These include persistent regional inequality, declining trust in national institutions, and increasing political polarisation.

Cultural or linguistic groups may begin asserting stronger identity claims, while local leaders demand greater administrative control.

In some cases, early signs also include:

Growth of separatist political parties

Tensions over natural resource distribution

Regional refusal to comply with central policies

Unequal access to natural resources such as oil, water or minerals often intensifies territorial tensions. Regions rich in resources may demand a greater share of revenue or control over extraction.

If the central government is perceived as unfair or exploitative, regional movements may strengthen, arguing for autonomy to manage resources locally.

Prolonged disputes over resource rights can escalate into demands for full independence, especially if local identity is already strong.

External actors can influence internal divisions by providing political, financial or diplomatic support to separatist groups. This may legitimise demands for autonomy or independence.

Cross-border cultural ties can also encourage neighbouring states to back separatist claims.

However, involvement may increase instability, particularly when external support deepens internal mistrust or heightens competition for territory.

The outcome depends on both internal aspirations and the central government’s willingness to compromise. Groups may accept autonomy if it ensures cultural protection, local decision-making and resource control.

Regions are more likely to push for independence if:

Historical grievances are severe

They perceive economic benefits from separation

Central authority is weak or delegitimised

International recognition prospects also shape whether movements stop at autonomy or pursue statehood.

Physical barriers such as mountains, deserts or long distances can make central governance more difficult, enabling regions to develop distinct identities over time.

Isolated regions may build stronger internal cohesion, which can support autonomy or secession movements.

Challenging terrain may also hinder the central state’s ability to enforce control, providing strategic advantages to groups seeking greater self-rule.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Identify one contemporary example of state disintegration and explain briefly why it occurred.

Mark scheme

1 mark – Identifies a valid contemporary example of state disintegration (e.g., Sudan/South Sudan, the former Soviet Union, Yugoslavia).

1 mark – Provides a basic explanation of why disintegration occurred (e.g., ethnic conflict, political instability, regional inequality).

1 mark – Offers an additional relevant detail that strengthens the explanation (e.g., prolonged civil war, collapse of central authority, historical grievances).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Evaluate how devolution through fragmentation can reshape the political and spatial organisation of a state. Refer to one or more real-world examples in your answer.

Mark scheme

1 mark – Defines or accurately describes devolution through fragmentation.

1 mark – Explains at least one political consequence (e.g., increased regional autonomy, weakened central governance, new administrative structures).

1 mark – Explains at least one spatial consequence (e.g., redrawing of internal boundaries, uneven development patterns, new or shifting territorial units).

1 mark – Uses one relevant real-world example (e.g., Spain’s autonomous communities, the UK’s devolved nations, Canada’s Quebec, or similar).

1–2 additional marks – Provides evaluative commentary, such as weighing differing impacts, addressing both positive and negative outcomes, or comparing multiple cases.