AP Syllabus focus:

‘Agricultural practices are influenced by the physical environment and climate, including Mediterranean and tropical climates.’

Agricultural systems develop in direct response to physical conditions. Climate, soils, and landscape features shape farmers’ decisions about crops, livestock, technologies, and land-use patterns across global regions.

Physical Environment and Its Influence on Agriculture

The physical environment refers to the natural conditions that shape human activity, including climate, topography, soils, and water availability. These factors strongly influence which farming practices are possible or efficient in a given place. Farmers must adapt their methods to environmental constraints, making geographic conditions a central force in the spatial organization of agriculture.

Climate as the Primary Control

Climate exerts the greatest influence on agricultural choices because crops and animals have specific temperature and moisture requirements. The two most important components—temperature and precipitation—determine growing seasons, evapotranspiration rates, and the risk of drought or frost. Seasonal variations also affect planting schedules, labor patterns, and long-term investment in agricultural infrastructure such as irrigation.

Climate: The long-term average of temperature, precipitation, and atmospheric conditions in a region, shaping environmental possibilities for agricultural production.

Seasonality matters as much as annual conditions. For example, regions with distinct wet and dry seasons require crops capable of tolerating moisture fluctuations or the installation of water-management systems. Conversely, regions with evenly distributed rainfall support intensive cultivation without the same irrigation demands.

A wide climatic spectrum—from tropical to polar—creates different agricultural opportunities.

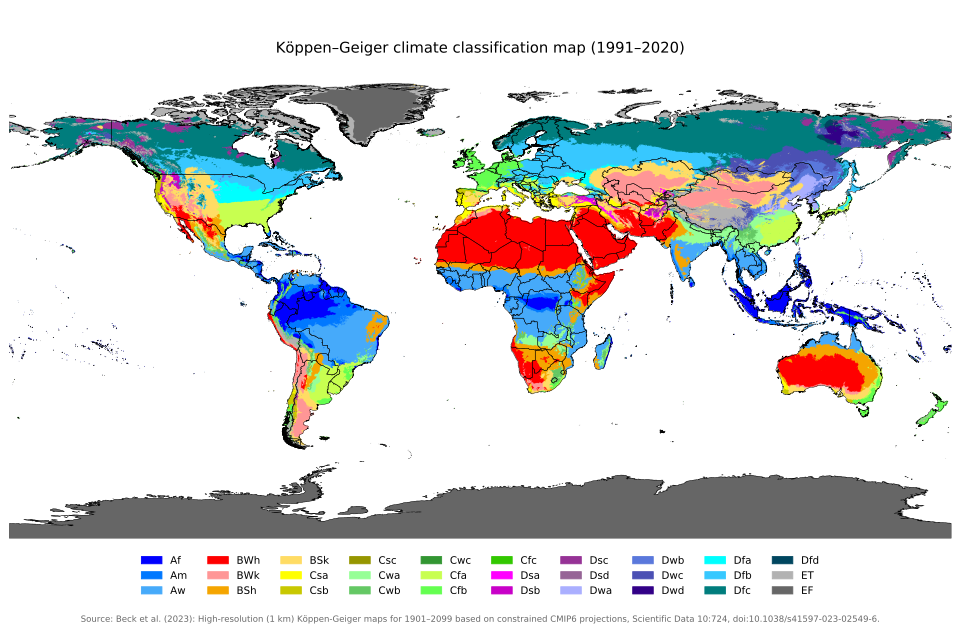

Köppen–Geiger climate classification map showing the global distribution of major climate zones. The tropical (A) and Mediterranean (Csa/Csb) regions highlighted on the map correspond to areas where distinctive agricultural systems have developed. The map includes other climate zones beyond this subtopic but provides useful environmental context. Source.

Farmers in warm, wet climates grow crops requiring abundant moisture, while farmers in cooler or drier climates emphasize drought-tolerant or cold-resistant species.

Soil Quality and Fertility

Soil characteristics, including nutrient content, acidity, and texture, influence crop selection and the intensity of land use. Fertile soils encourage continuous cultivation, while nutrient-poor soils require fallowing, shifting cultivation, or heavy fertilizer inputs. Physical properties such as drainage also determine whether fields are suitable for root crops, grain production, or grazing.

Topography and Landforms

Topography affects machinery use, erosion risk, and methods of cultivation. Flat plains allow mechanization and large-scale crop farming, while steep slopes require terracing or the cultivation of low-intensity crops. River valleys provide fertile soils and reliable water, supporting dense agricultural settlements.

Water Availability and Hydrology

Rainfall levels and groundwater access determine whether irrigation is necessary. Water-scarce environments often rely on drought-resistant crops or pastoralism. Regions with regular flooding, such as monsoon areas, support wet-rice agriculture. Hydrology thus influences economies of scale, labor demands, and settlement patterns.

Climate Zones and Agricultural Choices

The AP syllabus specifically highlights Mediterranean and tropical climates because they demonstrate how distinctive environments produce specialized agricultural systems.

Mediterranean Climate Agriculture

Mediterranean climates occur in coastal zones along roughly 30–40° latitude, characterized by warm, dry summers and mild, wet winters. The strong seasonality shapes farming decisions:

Farmers emphasize drought-resistant tree crops such as olives, grapes, and citrus, which can withstand prolonged summer dryness.

Olive grove in a Mediterranean climate region on the island of Thassos, Greece. The image shows mature olive trees adapted to seasonal summer dryness and limited soil moisture. It focuses on olives and does not depict other Mediterranean crops such as grapes or citrus, which are also typical of this climate. Source.

Winter rains support winter cereals such as wheat and barley.

Livestock, especially sheep and goats, graze on hilly terrain unsuitable for intensive plowing.

Farmers adapt to water scarcity by using drip irrigation, selecting hardy perennial plants, and planting widely spaced orchards to reduce competition for moisture.

Mediterranean Climate: A climate zone with dry, warm summers and mild, wet winters, supporting specialized perennial crops such as olives and grapes.

The landscape is often fragmented into terraced hillsides, reflecting the need to manage limited soil depth, reduce erosion, and maximize arable land.

Tropical Climate Agriculture

Tropical climates are warm year-round, with high insolation and significant precipitation. These conditions support rapid vegetative growth and long growing seasons. Farmers in tropical regions often rely on crops such as:

Rice, especially in monsoon regions

Cassava, yams, and other root crops

Bananas and plantains

Cacao, coffee, and sugarcane, which thrive in warm, wet conditions

However, tropical soils—especially lateritic or oxisol soils—tend to be nutrient-poor due to intense weathering. This leads to agricultural adaptations such as:

Shifting cultivation, allowing soil recovery

Use of fertilizers or mulching to maintain fertility

Irrigation systems for paddy rice

Agroforestry practices that mimic natural forest structure

Shifting Cultivation: An extensive farming system in which farmers clear land, cultivate it for a few years, and then allow it to regenerate naturally.

Because tropical climates support multiple cropping seasons, labor demands remain high, and many regions rely on smallholder farms or plantation systems.

Human Adaptation to Environmental Constraints

Farmers adjust their techniques to environmental limitations, creating diverse agricultural systems:

Irrigation counters water scarcity in arid or seasonal climates.

Crop rotation maintains soil fertility where nutrients are limited.

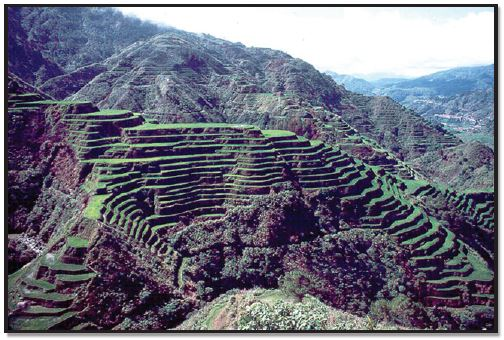

Terracing reduces erosion in mountainous areas.

Rice terraces in a humid, mountainous environment demonstrating how slopes are reshaped into stepped fields to control water flow and reduce erosion. These terraces support water-intensive rice cultivation common in tropical and monsoon climates. The source identifies the location as the Philippines, adding regional context to this adaptation. Source.

Drainage systems convert wetlands to arable land.

Crop–livestock integration balances nutrient cycles in mixed systems.

These adaptations demonstrate the dynamic relationship between the physical environment and agricultural decision-making. Farmers continually negotiate trade-offs between ecological conditions, economic demands, and cultural practices, leading to geographically diverse patterns of land use.

FAQ

Microclimates create small areas with distinct temperature, sunlight, or moisture conditions. Farmers often adapt crop choices accordingly.

For example, south-facing slopes may receive more solar radiation, allowing earlier planting dates or the cultivation of heat-tolerant crops.

Sheltered valleys may retain moisture, making them better suited for vegetables or fruit orchards.

These variations can lead to highly localised patterns of land use even within a single climate zone.

Perennial crops such as olives and grapes survive long dry summers because they develop deep root systems that access moisture stored in the soil.

They also tolerate irregular rainfall patterns and require fewer soil disturbances than annual crops, reducing erosion on sloping land.

This makes them particularly well suited to Mediterranean landscapes where water management and soil conservation are essential.

High humidity in tropical climates creates ideal conditions for fungal and bacterial diseases to spread rapidly.

Common impacts include:

• Greater need for disease-resistant crop varieties

• Higher dependence on crop rotation to break pest cycles

• Increased labour requirements for monitoring and removal of infected plants

These disease pressures shape both crop choice and the intensity of field management.

Steep slopes accelerate runoff, reducing the time water has to infiltrate into the soil. The faster the runoff, the more topsoil is removed.

Farmers on steep terrain often rely on terracing, contour ploughing, or planting ground-cover crops to slow water movement.

Without these measures, soil fertility declines quickly, limiting long-term agricultural productivity.

Farmers must synchronise their agricultural calendar with the onset and retreat of the monsoon.

Typical strategies include:

• Planting rice immediately after the first heavy rains

• Using flood-tolerant varieties during peak rainfall

• Growing drought-resistant crops, such as millet, during the dry season

This seasonal rhythm strongly influences labour patterns, crop rotations, and storage systems in monsoon regions.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (2 marks)

Explain how climate influences farmers’ choices of crops in either a Mediterranean or a tropical climate.

Mark scheme (2 marks total)

• 1 mark for identifying a relevant climatic characteristic (e.g., dry summers in Mediterranean climates, high rainfall in tropical climates).

• 1 mark for linking that characteristic to a specific crop choice (e.g., olives suited to dry summer conditions; rice suited to monsoon rainfall).

Question 2 (5 marks)

Using examples, explain how two different elements of the physical environment (excluding climate) shape agricultural practices in a region of your choice.

Mark scheme (5 marks total)

• 1 mark for identifying a valid physical factor such as soil fertility, topography, or water availability.

• 1 mark for describing how the factor operates in the chosen region (e.g., steep slopes in the Andes).

• 1 mark for explaining the agricultural adaptation linked to that factor (e.g., terracing to prevent erosion).

• 1 mark for identifying a second, different physical factor.

• 1 mark for explaining the agricultural consequence of the second factor with clear regional relevance.