AP Syllabus focus:

‘Extensive farming includes shifting cultivation, nomadic herding, and ranching.’

Extensive agriculture systems rely on large land areas, low labor inputs, and lower yields, shaping distinctive rural landscapes and influencing how societies use marginal or remote environments.

Characteristics of Extensive Agriculture Systems

Extensive agriculture refers to farming practices that use large amounts of land with minimal labor or capital inputs per unit of area. These systems typically appear in regions where population densities are low and land is plentiful relative to labor. Because extensive systems generate lower yields per acre than intensive systems, they often depend on the wide availability of land to remain viable.

Extensive systems are strongly influenced by environmental constraints such as climate, soils, and vegetation cover, which determine land suitability. They also evolve from cultural traditions, resource availability, and economic conditions.

Shifting Cultivation

Shifting cultivation is a form of extensive subsistence agriculture most common in tropical regions. It involves farmers clearing forest or bush through temporary use rather than permanent fields. Once soil fertility declines, farmers move to a new area and repeat the cycle.

Shifting Cultivation: A subsistence farming system in which farmers clear land, grow crops for several years until soil nutrients decline, and then relocate to a new plot.

To carry out this system, communities rely heavily on knowledge of local ecosystems and seasonal cycles. Shifting cultivation supports small populations because each cycle requires long periods for soil nutrient regeneration.

Key Processes in Shifting Cultivation

Land clearing, often using slash-and-burn techniques to remove vegetation and add short-term soil nutrients.

Short-term cropping, typically 2–3 years, during which farmers grow staple crops adapted to tropical conditions.

Fallow periods that allow natural forest regrowth and soil recovery, sometimes lasting more than a decade.

Rotational land use, preventing permanent settlement on any single plot.

These long fallow periods mean large areas are needed, reinforcing the system’s extensive nature.

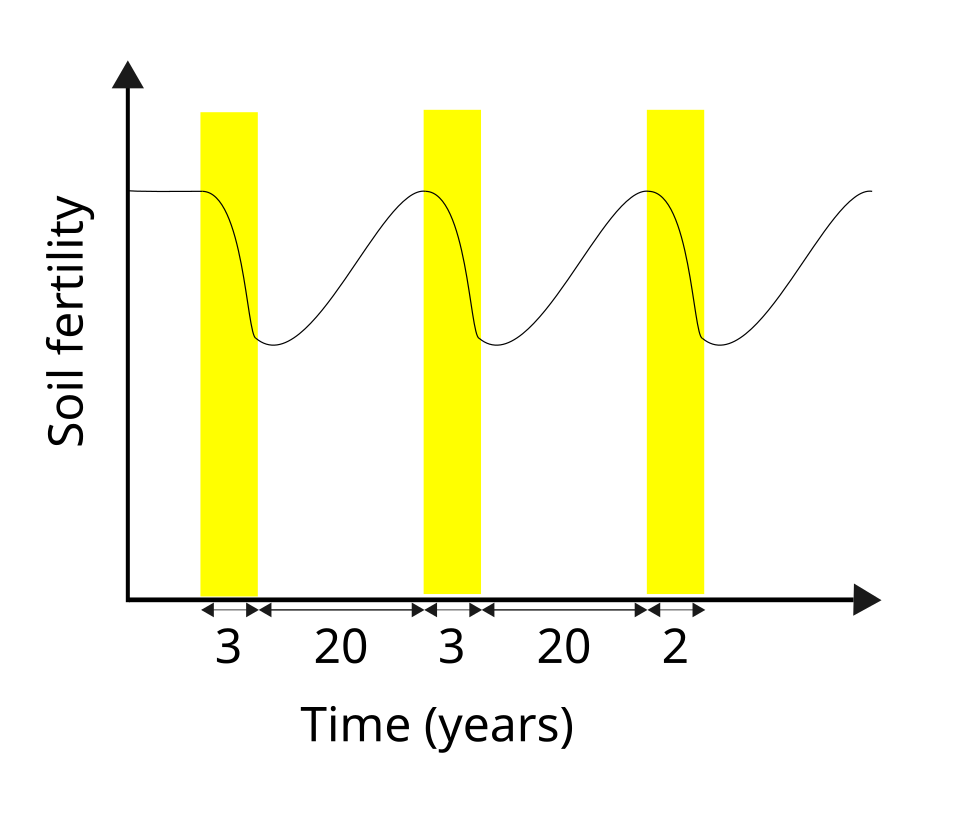

This shifting cultivation cycle alternates short periods of cropping with long fallow periods to restore soil fertility.

Diagram showing soil fertility over time in a sustainable shifting-cultivation system. Yellow bands represent brief cropping periods, while white intervals show long fallow phases when vegetation regrows and nutrients replenish. The focus on soil-fertility dynamics slightly exceeds the AP syllabus but directly supports the explanation of extensive land use and long recovery periods. Source.

Nomadic Herding

Nomadic herding (also called pastoral nomadism) occurs in arid, semi-arid, and mountainous climates where growing crops is difficult. Instead of cultivating land, communities raise livestock such as camels, sheep, goats, or reindeer, moving seasonally to access fresh pasture.

Nomadic Herding: A form of extensive subsistence agriculture in which herders move livestock seasonally across large territories to find grazing land and water.

Seasonal migration patterns vary by region but often follow established routes passed down through generations. These patterns balance the needs of the herd with the carrying capacity of fragile landscapes.

Spatial Patterns in Nomadic Herding

Transhumance, a seasonal movement between lowland winter pastures and highland summer pastures.

Full nomadism, involving continuous movement without permanent settlements.

Low population densities, making this system compatible with harsh environments.

Large land areas, required because natural vegetation is sparse.

The reliance on natural pasture reinforces the extensive qualities of the system, as herders must spread animals widely to prevent overgrazing.

In nomadic herding (pastoral nomadism), households move with their herds between seasonal pastures, often following long-established routes through arid or semi-arid landscapes.

Ranching

Ranching is a commercial form of extensive agriculture found primarily in more developed economies or export-oriented regions. Unlike nomadic herding, ranching typically occurs on permanently owned or leased land where livestock roam freely over large ranges.

Ranching: A commercial agricultural system in which livestock graze over expansive tracts of land, producing meat or other animal products for regional or global markets.

Ranching emerged historically in regions such as the American West, Argentina’s Pampas, and parts of Australia. These areas share characteristics such as spacious grasslands, limited rainfall, and low rural population density.

Features of Ranching Systems

Extensive land use, with cattle or sheep grazing on natural pasture rather than fenced, intensively managed fields.

Low labor input, as animals often roam and feed without constant supervision.

Commercial orientation, with products entering national or global commodity chains.

Adaptation to semi-arid climates, where crop farming is less feasible.

Because ranching is market-oriented, it often reflects economic drivers such as land prices, transportation networks, and demand for animal products. Yet its spatial footprint remains extensive due to the need for large grazing territories.

Commercial ranching relies on extensive grazing over large parcels of land, with relatively low labor input per acre but significant land and capital requirements.

Cattle grazing across a broad meadow landscape near Pailan, West Bengal. This scene illustrates how extensive ranching systems disperse livestock over large open areas rather than confining them to intensively managed pastures. The Indian location extends beyond the AP syllabus but demonstrates the global relevance of extensive grazing systems. Source.

Environmental and Cultural Contexts

Each extensive agriculture system reflects a balance between environmental conditions and cultural practices. Shifting cultivation works effectively in tropical forests where soil nutrients regenerate naturally. Nomadic herding fits drylands where mobility reduces pressure on fragile ecosystems. Ranching suits grassland regions where capital investment and market access support commercial livestock production.

Common Characteristics Across Extensive Systems

Large land requirements due to low productivity per acre.

Low labor intensity, distinguishing them from intensive farming systems such as market gardening or mixed crop–livestock agriculture.

Close ties to climate, especially in regions with limited rainfall or poor soil fertility.

Mobility or large grazing territories, particularly in herding-based systems.

Although these systems differ in scale, purpose, and cultural tradition, they all embody the core principle of extensive agriculture: maximizing land area while minimizing labor or capital inputs.

FAQ

Shifting cultivation often features root crops and grains such as cassava, yams, taro, millet, and upland rice. These crops tolerate nutrient-poor soils and short cultivation periods.

They are well suited because:

• They mature quickly.

• They require minimal external inputs.

• They regrow or reseed easily, supporting low-intensity farming.

• Their yields remain reliable even as soil fertility begins to decline.

Movement is based on a combination of environmental cues and long-standing cultural knowledge.

Key factors include:

• Seasonal availability of water and pasture.

• Weather variability, especially rainfall patterns.

• Traditional migration routes negotiated between groups.

• The condition of the herd, which signals when grazing pressure is becoming unsustainable.

Nomadic herding increasingly struggles with shrinking access to rangelands as governments expand protected areas, farms, and urban settlements.

Additional pressures include:

• National borders restricting movement.

• Climate change intensifying drought cycles.

• Competition with commercial livestock operations.

• Policies that encourage sedentarisation, reducing cultural autonomy.

Ranchers often adopt selective intensification while keeping grazing extensive, allowing them to compete economically.

Typical adaptations include:

• Improving breeds for meat or wool productivity.

• Supplementary feeding during droughts.

• Rotational grazing to maintain pasture health.

• Using technology (GPS, remote water monitoring) to manage large herds efficiently without increasing labour intensity dramatically.

Extensive systems need large land areas to compensate for low productivity per unit of land. Such expanses are usually only available where population densities are low.

Low density also reduces land-use conflict, making it easier for:

• Pastoralists to migrate seasonally.

• Farmers to rotate fields across long fallow cycles.

• Ranchers to manage large herds without intensive fencing or supervision.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one reason why shifting cultivation is classified as an extensive agricultural system.

Mark scheme:

• 1 mark for identifying a valid characteristic of extensive agriculture (e.g., requires large land areas, low labour input per unit area).

• 1 mark for connecting this characteristic directly to shifting cultivation (e.g., long fallow periods mean farmers must rotate over wide areas).

• 1 additional mark for a clear explanation of why this makes the system extensive (e.g., because productivity per acre is low and relies on abundant land rather than intensive inputs).

(Max 3 marks)

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Assess how environmental conditions influence the spatial distribution of nomadic herding and ranching as extensive agricultural systems.

Mark scheme:

• 1 mark for describing the environmental conditions linked to nomadic herding (e.g., arid or semi-arid climates, scarce vegetation, seasonal pastures).

• 1 mark for explaining how these conditions encourage mobility and large land areas for grazing.

• 1 mark for describing the environmental conditions that support ranching (e.g., grasslands, semi-arid climates, large expanses of pasture).

• 1 mark for explaining how these conditions support commercial livestock rearing at low labour density.

• 1–2 marks for evaluative or comparative insight (e.g., contrasting mobility in herding with fixed land tenure in ranching; noting how both depend on wide land availability but differ in economic organisation).

(Max 6 marks)