AP Syllabus focus:

‘Food systems respond to urban farming, CSA, organic farming, value-added specialty crops, fair trade, local-food movements, and dietary shifts.’

Food-system movements and individual dietary choices reshape modern agriculture by encouraging alternative production methods, ethical consumption, and local sourcing, influencing how food is grown, distributed, and valued globally.

Food-System Movements and Their Influence on Agriculture

Food-system movements challenge conventional industrial agriculture by promoting sustainability, local engagement, ethical consumption, and health-oriented production. These movements alter agricultural landscapes by creating new markets, supporting small-scale farmers, and shaping consumer expectations for transparency and environmental responsibility.

Urban Farming

Urban farming refers to agricultural production within cities, ranging from rooftop gardens to community plots. It expands food access and strengthens local food networks.

Urban agriculture reduces food deserts—areas with limited access to affordable, nutritious foods—by situating production closer to consumers.

An urban farm integrates agricultural production directly into a dense city environment, showing how unused urban land can support fresh-food access. These sites help reduce food deserts by placing nutritious produce close to residents. The image also demonstrates the spatial overlap of agriculture and the built environment. Source.

Community-Supported Agriculture (CSA)

CSAs are programs where consumers purchase a share of a farm’s output in advance, receiving regular deliveries of locally grown products.

This model strengthens farmer–consumer ties and helps farms gain financial stability by reducing risk. CSAs allow consumers to directly support sustainable practices and seasonal diets through long-term commitment to a specific farm.

Community-Supported Agriculture (CSA): A food-distribution model in which consumers subscribe to a farm’s harvest and receive periodic shares of its produce.

CSAs encourage a more transparent and participatory food system, empowering individuals to make choices aligned with environmental and social values.

Organic Farming

Organic farming excludes synthetic fertilizers, pesticides, herbicides, and genetically modified organisms. It relies on ecological principles such as soil regeneration, biodiversity, and natural nutrient cycles.

Organic agriculture appeals to consumers seeking food produced without chemical inputs and supporting environmental stewardship.

Organic Farming: A method of cultivation that avoids synthetic chemicals and GMOs, emphasizing biological processes, soil health, and ecological balance.

Demand for organic products influences land-use patterns, encouraging farmers to adopt practices such as crop rotation, composting, and natural pest management.

Value-Added Specialty Crops

Value-added specialty crops undergo processing or enhancement that increases their market value—such as artisanal cheeses, cold-pressed oils, or specialty preserves.

This approach allows farmers to diversify revenue streams and strengthen local brands. It can also reshape rural economies by supporting small-scale entrepreneurship and niche markets.

Fair Trade

Fair trade systems certify and promote goods produced under equitable conditions. They guarantee minimum prices, safe working environments, and sustainable environmental practices for farmers—especially in the Global South.

Fair trade encourages ethical consumption by providing transparency in commodity chains and ensuring smallholder farmers receive a fair share of profits.

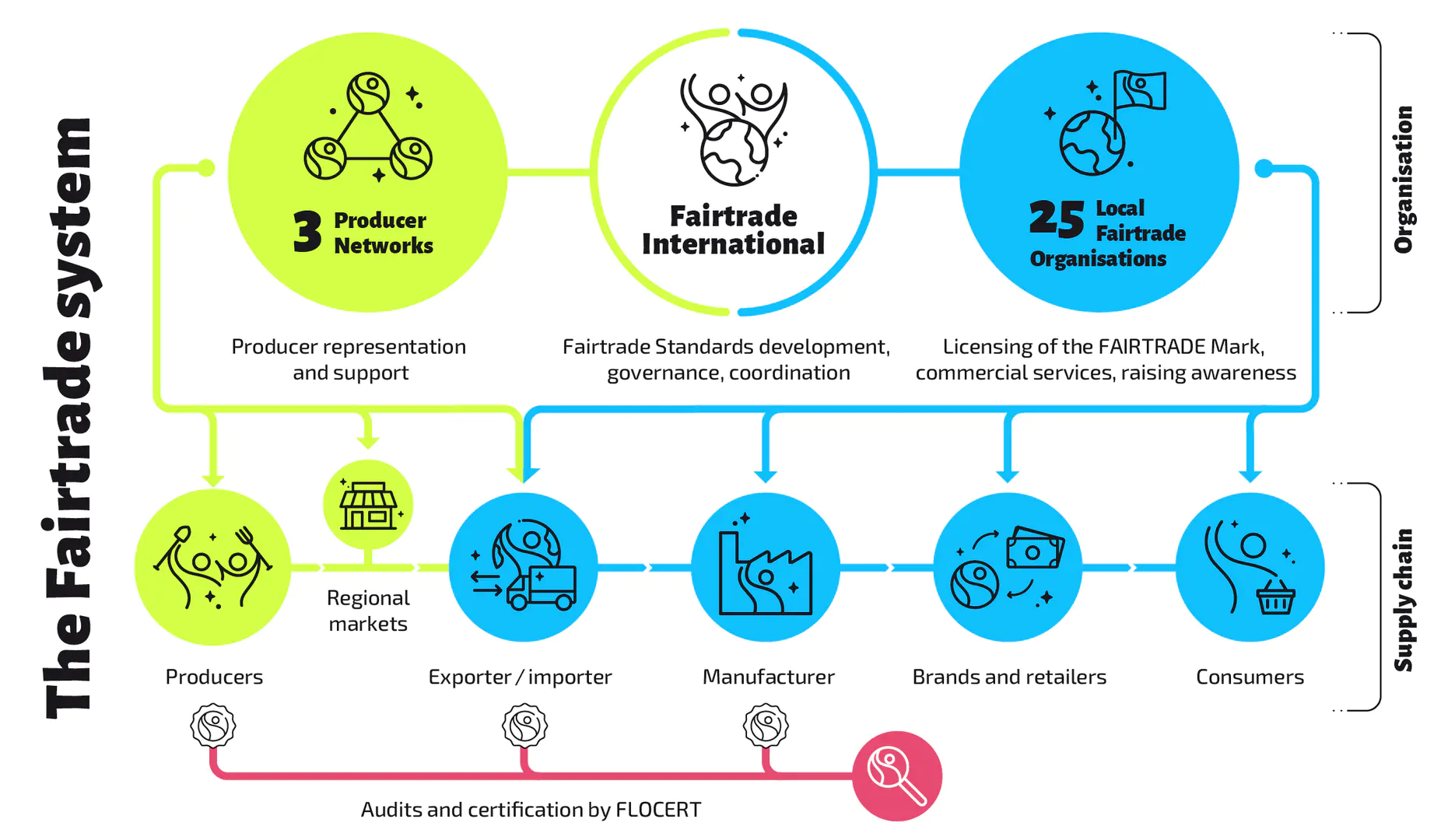

This diagram illustrates the structure of the Fairtrade system, mapping how certified goods move from producers through exporters, manufacturers, and retailers to consumers. It highlights how oversight organizations ensure ethical and sustainable production. Some institutional elements extend beyond the syllabus but help clarify how the system operates. Source.

Fair Trade: A certification and movement ensuring that producers, often in developing countries, are paid fair wages and operate under safe and sustainable conditions.

This movement responds to growing concerns about labor exploitation, global inequality, and degrading environmental conditions in conventional export-driven agriculture.

Local-Food Movements

Local-food movements promote consumption of products grown within a defined geographic area. These movements emphasize freshness, reduced transportation emissions, and community resilience.

Consumers who “eat local” support nearby farms and reduce reliance on long, complex supply chains that can compromise freshness and increase environmental cost.

Local-food movements often intersect with farmers’ markets, CSAs, and urban farming initiatives, creating integrated local food economies.

Dietary Shifts and Individual Choice

Individual dietary choices increasingly influence agricultural systems. Rising consumer interest in plant-based diets, reduced meat consumption, and sustainably sourced foods shapes production patterns.

Health concerns, ethical motivations, and environmental awareness all contribute to changing demand.

Dietary Shift: A change in typical eating patterns, often motivated by health, environmental, ethical, or cultural factors.

These shifts encourage growth in industries such as plant-based proteins, specialty grains, and sustainably sourced livestock production.

How Consumer Choice Reshapes Commodity Chains

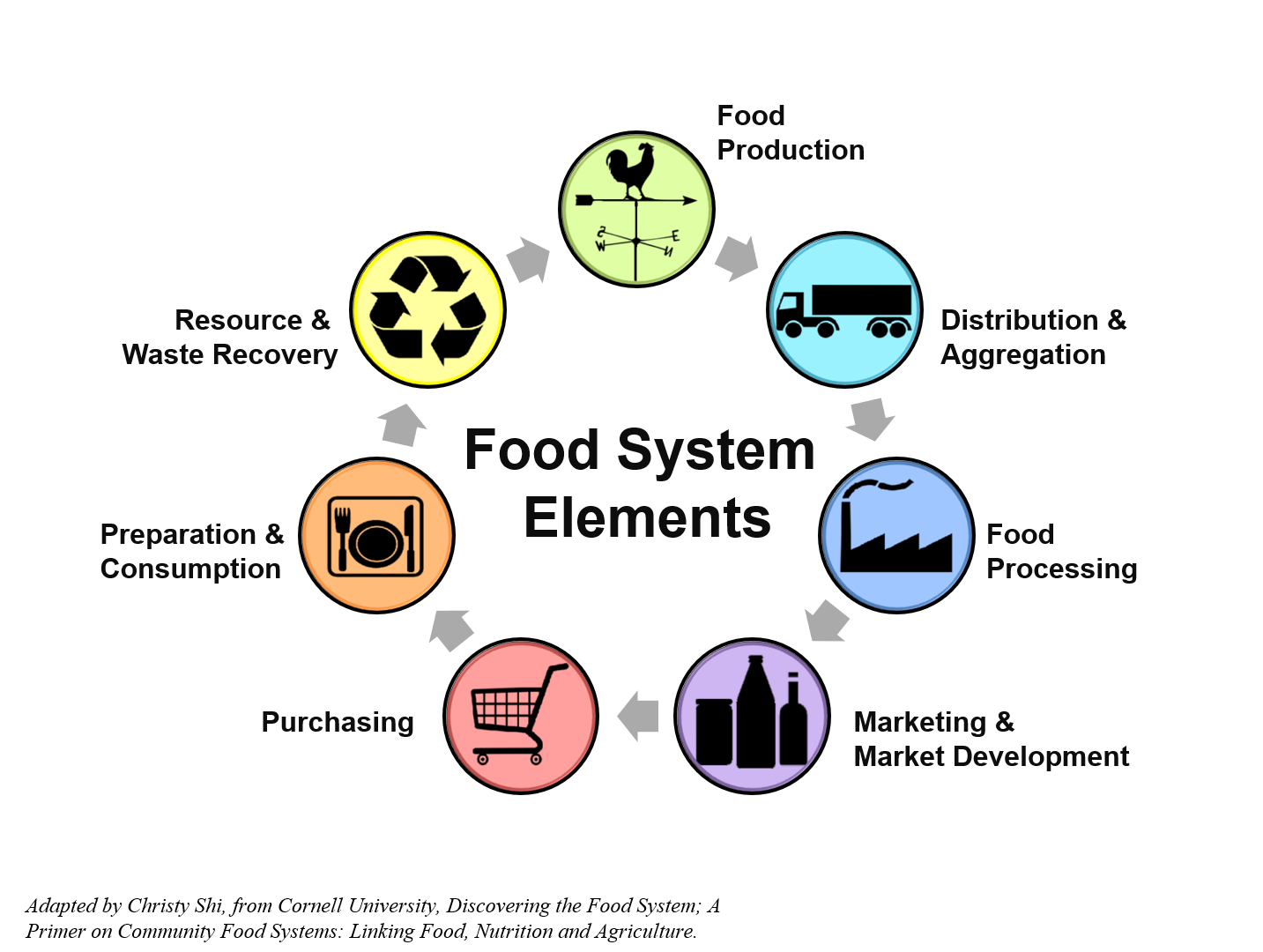

Food-system movements influence each stage of commodity chains—from production and processing to distribution and retail.

The diagram outlines key elements within a food system, showing how food moves from production to consumption and eventual waste recovery. This visual helps illustrate how food-system movements can reshape multiple points along the chain. The inclusion of waste recovery extends slightly beyond the syllabus but supports a holistic understanding. Source.

Expansion of Alternative Markets

Alternative markets emerge when consumers seek food-system movements that reject industrialized norms. These include:

Farmers’ markets, which connect buyers directly with producers

Cooperatives, where members share ownership of food retail spaces

Specialty grocers, emphasizing organic, local, and ethically sourced goods

These markets create stable demand for small-scale farmers and offer consumers direct engagement with their food sources.

Environmental and Social Implications

Food-system movements promote reduced chemical inputs, shorter supply chains, and improved labor conditions. While not universally implemented, these practices can contribute to lower ecological footprints and strengthened rural economies.

Individual choices accumulate into broader societal trends capable of reshaping agricultural landscapes, market structures, and the global food economy.

FAQ

Food-system movements often redirect consumer spending towards smaller producers through mechanisms such as farmers’ markets, CSAs, and direct online ordering. These shorten supply chains and reduce the share of revenue captured by intermediaries.

They also allow small farms to specialise in niche crops, value-added goods, or organic produce, enabling higher price points.

However, small farms may face challenges such as certification costs, labour intensity, and vulnerability to fluctuating demand.

CSA programmes face constraints related to logistics, consumer commitment, and seasonal variability. Many households are reluctant to commit to upfront payment or weekly collections.

Farms may struggle with:

• unpredictable yields

• maintaining variety in weekly boxes

• distribution beyond a small radius

Additionally, CSAs may be less accessible in low-income or rural areas where transport, time, or cost restrict participation.

Changing diets, such as rising plant-based consumption, reshape which crops become globally traded. Demand increases for pulses, nuts, and speciality grains used in plant-based products.

Supply chains must adapt by investing in new processing facilities, developing alternative protein markets, and sourcing ingredients from different regions.

These changes can also create vulnerabilities when demand surges faster than production capacity.

Organic certification can open access to premium markets, allowing farmers to earn higher prices for their crops. It may also encourage sustainable land management.

But certification requires:

• inspections

• record-keeping

• fees

• conversion periods

These costs can be prohibitive for smallholders, creating inequalities between farmers who can meet certification standards and those who cannot.

Local-food systems prioritise proximity, freshness, and small-scale production, which limits expansion over long distances. Transporting local goods nationally undermines the movement’s core principles.

Other limiting factors include:

• limited land availability near cities

• seasonal production constraints

• higher labour inputs

• higher prices than mass-produced alternatives

As a result, local-food movements tend to remain regionally focused rather than becoming national distribution networks.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which local-food movements can influence agricultural production.

Mark Scheme:

• 1 mark for identifying a basic influence (e.g., increased demand for locally grown food).

• 1 mark for describing how this changes farming practices (e.g., farmers shifting to crops suited to local markets or shorter growing cycles).

• 1 mark for explaining a geographical consequence (e.g., reduced reliance on long-distance transport or strengthened regional food systems).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Discuss how two different food-system movements have affected relationships between consumers and producers in contemporary agriculture.

Mark Scheme:

• 1 mark for identifying the first food-system movement (e.g., Community-Supported Agriculture, organic farming, fair trade).

• 1–2 marks for explaining how this movement changes consumer–producer relationships (e.g., increased transparency, direct financial support, trust-building, ethical engagement).

• 1 mark for identifying a second food-system movement.

• 1–2 marks for explaining how this second movement reshapes consumer–producer interactions (e.g., certification systems, ethical guarantees, demands for environmentally responsible production).