AP Syllabus focus:

‘Processing and market locations, economies of scale, distribution systems, and government policies shape food-production practices.’

Economic forces and government policies profoundly influence how food is produced, processed, transported, and marketed, shaping the spatial organization and efficiency of modern agricultural systems.

Economics and Policy in Food Production

Food production operates within a global economic framework where processing locations, market access, economies of scale, and policy decisions determine agricultural patterns. The geography of food systems reflects how farmers, corporations, and governments respond to costs, incentives, and distribution needs.

Processing and Market Locations

Agricultural goods rarely move directly from farms to consumers; instead, they pass through processing facilities that add value and make products suitable for distribution.

Factors Influencing Processing Locations

Processing sites tend to develop in places where economic conditions maximize efficiency. These locations often reflect:

Proximity to raw materials to reduce bulk transportation costs.

Access to labor and specialized machinery.

Connections to distribution networks, such as railways, highways, and ports.

Market size and population density that support food manufacturing.

Spatial Patterns

Because perishables and bulk goods differ in handling needs, processing locations vary:

Perishable products (milk, fruits, vegetables) often require nearby processing plants to maintain freshness.

Bulk or storable products (grains, oils, canned goods) may be processed farther from farms, often near major markets.

Global supply chains encourage clustered industrial zones, where manufacturers, logistics firms, and cold-storage facilities develop together.

Economies of Scale in Food Production

Economies of scale refer to the cost advantages gained as production volume increases.

Economies of Scale: The reduction in per-unit production cost that occurs when output increases and operations become more efficient.

Large agribusinesses benefit from economies of scale through:

Mechanized equipment that lowers labor costs.

Centralized management systems that reduce administrative expenses.

Bulk purchasing of seeds, fertilizers, and pesticides.

Streamlined distribution supported by sophisticated logistics technology.

Smaller farms may struggle to compete because they often face higher unit costs, limited access to capital, and reduced bargaining power with processors and retailers.

Distribution Systems and Spatial Efficiency

Distribution connects farms, processors, and consumers through a coordinated network of transportation and storage facilities.

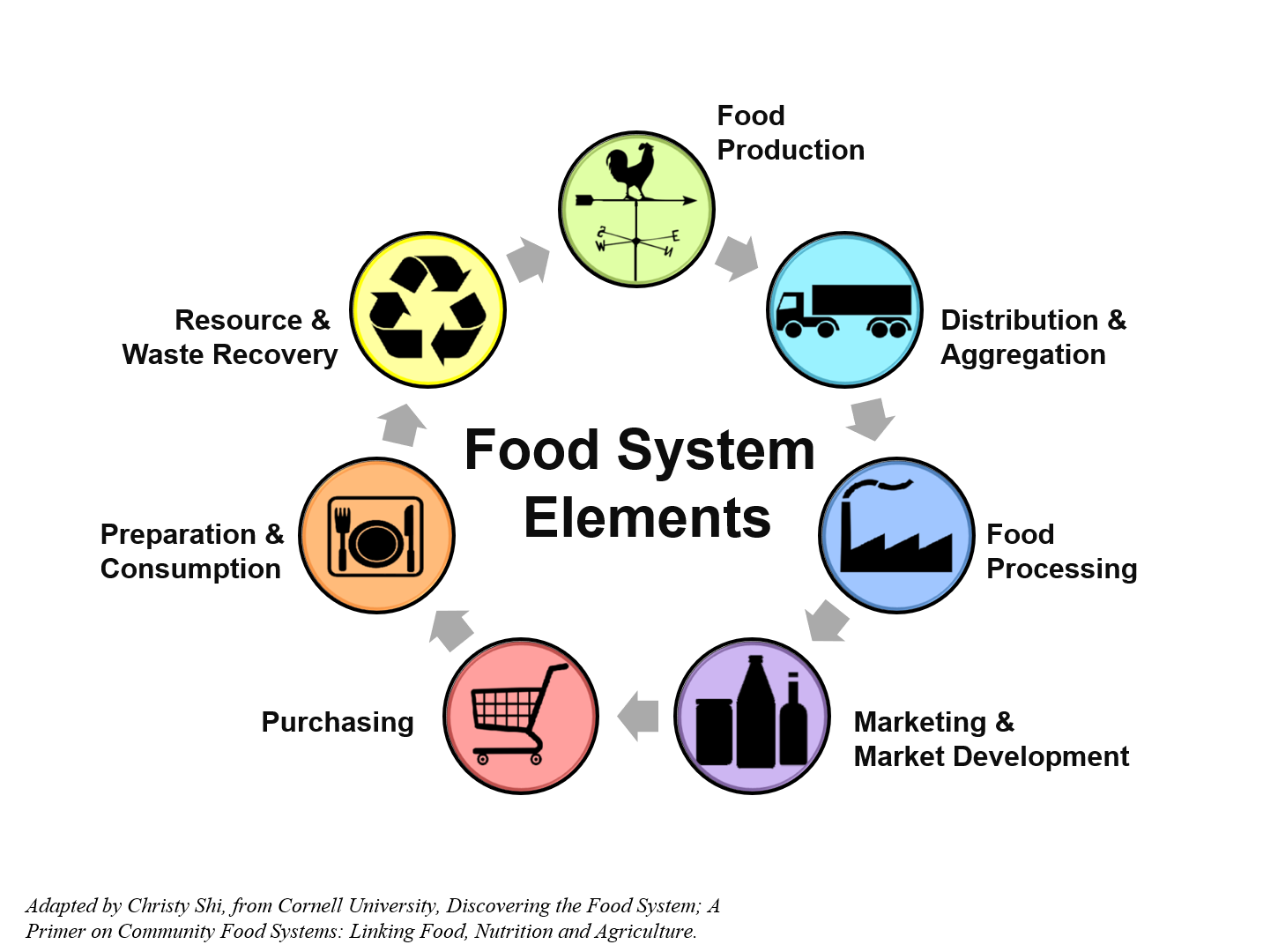

This diagram illustrates the major stages of a local food system, from food production through processing, distribution and aggregation, marketing, purchasing, and preparation and consumption. It also includes resource and waste recovery, which extends slightly beyond the AP syllabus but helps students visualize the cyclical nature of food systems. Source.

Key Components of Agricultural Distribution

Transportation networks including highways, rail corridors, ports, and air cargo hubs.

Cold-chain infrastructure essential for perishable goods.

Warehousing and storage that maintain product quality and regulate supply.

Retail and wholesale markets where goods enter consumer-oriented channels.

Spatial Considerations

The structure of distribution systems shapes agricultural geography:

Areas with stronger infrastructure attract more commercial farming.

Weak distribution networks can create regional disparities in food availability and profitability.

Global supply chains link export-oriented agriculture with international buyers, influencing where and how farmers produce crops.

Role of Government Policies in Food Production

Government intervention influences nearly every stage of food production, from land use and farm income to environmental protection and international trade.

Types of Government Policies

Subsidies that reduce farmers’ financial risks by supporting specific crops or production methods.

Price supports that keep staple crops financially viable even when market prices fall.

Regulations related to food safety, environmental impacts, and labor conditions.

Trade policies, including tariffs, quotas, and free-trade agreements, that shape global agricultural flows.

Infrastructure investment, such as building roads, irrigation systems, and storage facilities, which strengthens agricultural productivity.

Impacts on Agricultural Spatial Patterns

Policies can reshape the geography of food production by incentivizing certain crops, encouraging consolidation, or protecting rural livelihoods:

Subsidies may promote monocropping in regions where farmers depend on guaranteed payments.

Environmental regulations may shift production to areas with fewer restrictions or better natural conditions.

Trade agreements can open new markets, encouraging farmers to specialize in export crops.

Zoning and land-use rules influence the extent of farmland preservation versus conversion to urban uses.

Interactions Among Economics, Policy, and Agricultural Practices

The combination of economic forces and policy decisions generates complex outcomes:

Large-scale farms may consolidate further under policies that favor efficiency and high output.

Market-oriented agriculture often prioritizes crops with strong global demand.

Rural areas may experience economic shifts as processing facilities relocate based on transportation cost changes or labor availability.

Distribution bottlenecks, whether due to infrastructure limitations or regulatory barriers, can cause price volatility and supply shortages.

The Global Context

In a globalized economy, food production operates beyond national boundaries.

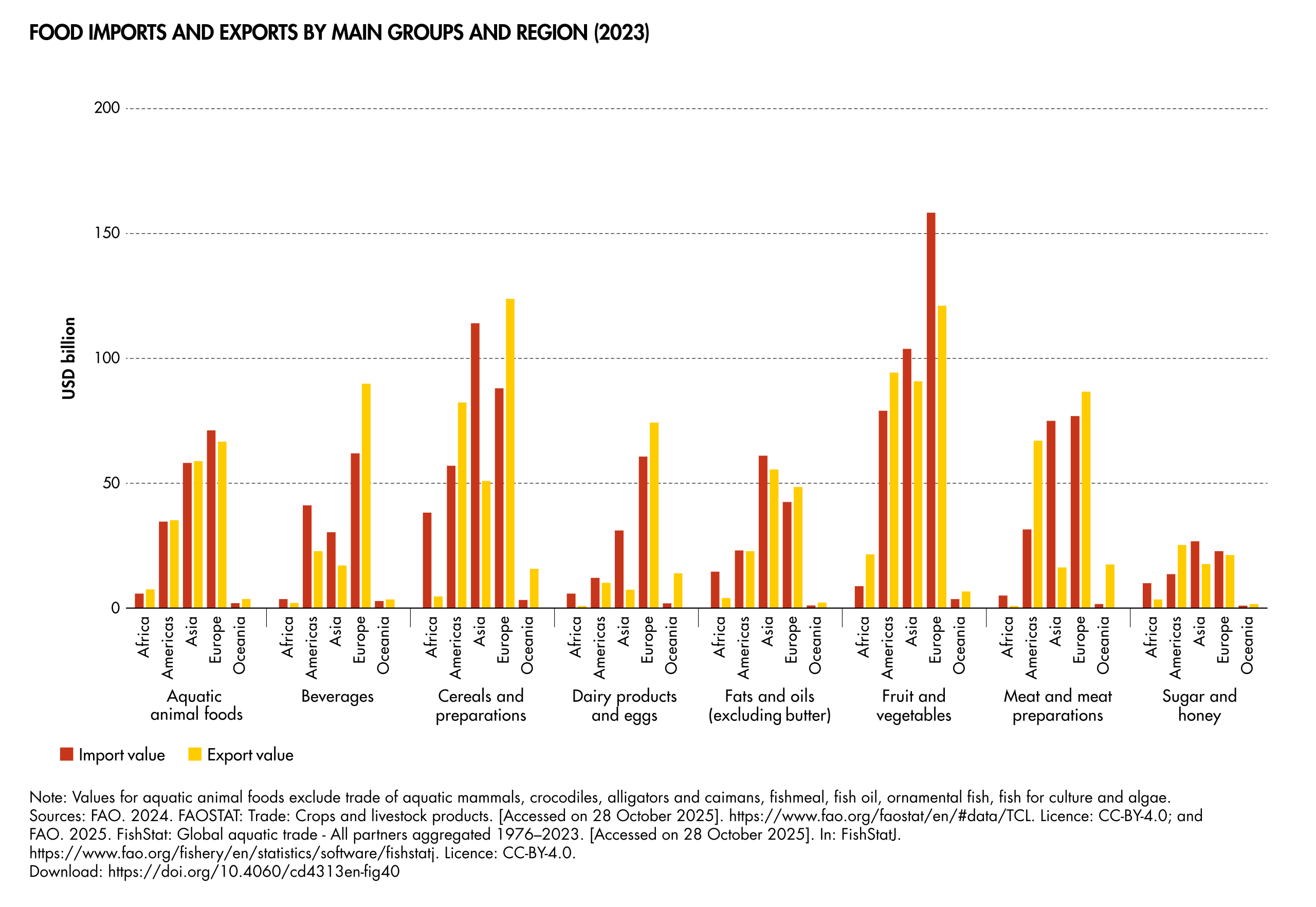

This graphic compares the value of imports and exports for major food product groups across world regions. Although it includes detailed monetary data beyond the AP syllabus, students can focus on the relative bar heights to understand regional trade dependence and export specialization. Source.

In a globalized economy, food production operates beyond national boundaries. Policies enacted in one country—such as export taxes or environmental limits—can influence international prices and reshape global trade routes. Economies of scale allow multinational agribusinesses to dominate production and distribution, creating a complex interplay between local farming practices and worldwide market forces.

FAQ

Subsidies provide direct financial assistance to farmers, often lowering production costs or guaranteeing income. Price supports raise or stabilise the selling price of particular crops.

This distinction matters geographically because:

Subsidies often influence what farmers choose to plant, shaping regional crop specialisation.

Price supports may keep otherwise uncompetitive regions in production, preserving farming in areas that might otherwise lose agricultural activity.

Different policies favour different scales of farming, affecting patterns of consolidation or persistence of small farms.

Processing plants may move to areas with cheaper labour, lower energy costs, or better access to national distribution networks.

Relocation also occurs when:

Major markets shift geographically.

Firms seek proximity to motorways, ports, or rail hubs.

Corporate consolidation places multiple plants into one larger, more efficient facility.

These movements can reshape local economies, even if farming patterns stay stable.

Trade agreements reduce tariffs and increase market access, encouraging countries to focus on crops for which they have cost or climatic advantages.

Specialisation emerges because:

Guaranteed market access reduces risk and encourages investment.

Countries shift towards export-oriented production for goods demanded internationally.

Competing domestic products may decline if imports become cheaper, changing national agricultural landscapes.

Cold-chain systems—refrigerated transport and storage—allow perishable goods to travel long distances without spoiling.

Their growing importance reflects:

Rising global demand for fresh produce, meat, and dairy.

Increased international trade in perishables.

Expansion of urban populations requiring stable food supplies.

Regions with robust cold-chain infrastructure gain an advantage in commercial farming, shifting investment and production towards areas with better facilities.

Environmental rules can impose costs related to water use, emissions, waste, or fertiliser application.

This can indirectly reinforce economies of scale because:

Large farms can more easily absorb compliance costs.

Bigger operations often have the capital to invest in cleaner technologies.

Smaller farms may find regulations financially burdensome, encouraging consolidation.

As a result, environmental policy can unintentionally promote larger farm sizes and more concentrated production regions.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which government policy can influence the spatial distribution of agricultural production.

Mark scheme

Award up to 3 marks:

1 mark for identifying a relevant government policy (e.g., subsidies, price supports, trade agreements, environmental regulations).

1 mark for describing how that policy affects farming decisions or land use.

1 mark for explaining how this leads to a change in the spatial distribution of agricultural production (e.g., concentration of certain crops, shift of production to or away from specific regions).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Using examples, analyse how economies of scale and distribution systems shape commercial food production at a national or global scale.

Mark scheme

Award up to 6 marks:

1 mark for a correct definition or explanation of economies of scale.

1 mark for explaining how large-scale operations reduce per-unit costs or increase efficiency.

1 mark for describing a feature of distribution systems (e.g., transport networks, cold-chain logistics, warehousing).

1 mark for explaining how distribution systems enable wider market access or allow producers to specialise.

Up to 2 additional marks for well-developed analysis using accurate examples showing links between economies of scale, distribution systems, and spatial patterns of commercial production.