AP Syllabus focus:

‘Women’s roles in food production, distribution, and consumption vary by place and by the type of agricultural production involved.’

Women participate in food systems worldwide, yet their roles vary greatly depending on cultural norms, economic structures, agricultural technologies, and regional development patterns influencing production and distribution.

Geographic Variation in Women’s Roles in Food Systems

Women’s involvement in food production, distribution, and consumption differs significantly across regions. These variations reflect social expectations, access to resources, agricultural practices, and political–economic systems shaping opportunities for participation.

Women in Food Production

In many parts of the world, particularly in developing regions, women form the backbone of small-scale agriculture. Their responsibilities are often shaped by the type of farming system and local land tenure norms.

In subsistence agriculture, especially in Sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, women frequently perform labor-intensive tasks such as planting, weeding, harvesting, and processing.

In commercial agriculture, women may be employed in plantation work, horticulture, or packing operations, though often with limited access to higher-paying or managerial positions.

In pastoral nomadism and extensive systems, gender roles can be more rigid, with women tending small livestock or processing dairy while men manage long-distance herding.

Gender division of labor is a foundational concept explaining how agricultural responsibilities differ between men and women. It reflects culturally assigned tasks and expectations, often restricting women’s access to technology, credit, and training.

Gender Division of Labor: The allocation of specific tasks to men or women based on cultural norms rather than biological or skill-based factors.

These patterns influence productivity, as women may rely on manual tools or traditional practices when they lack access to mechanization or improved seeds. Policies and reforms addressing land rights and agricultural extension services can significantly reshape women’s roles by granting greater autonomy in decision-making.

A woman farmer in Uganda discusses crops with an agricultural trainer, illustrating how extension services and new knowledge can change women’s decision-making power in farming. The interaction highlights the importance of access to information and technology, not just physical labor, in shaping women’s roles in food systems. The image includes extra contextual detail about coffee production that is not specifically required by the syllabus but effectively represents women’s engagement with modern agricultural support programs. Source.

Women in Food Distribution Networks

Women play vital roles in distributing food within local and regional markets, though their participation varies widely by region and economic system.

In many African urban markets, women dominate informal food vending, acting as crucial intermediaries between rural producers and consumers.

In Latin America, women frequently work in cooperatives, managing the sale of coffee, cacao, or artisanal foods.

In East and Southeast Asia, women often participate in wet markets and small-scale fisheries, controlling the sale and processing of fish or vegetables.

These distribution roles highlight the importance of informal economies, which rely on small-scale trading rather than formal corporate supply chains. Women’s participation in such networks provides income security, community cohesion, and diversified diets.

Informal Economy: Economic activity not regulated or taxed by the government, often based on small-scale or family-run enterprises.

Women in distribution frequently navigate complex social networks, transportation challenges, and market fluctuations, illustrating how local geographies shape economic opportunities.

Women in Food Consumption and Household Decision-Making

Across much of the world, women are the primary managers of household food consumption. Their responsibilities influence nutrition, food preferences, and budgeting.

Women often select crops for home gardens based on cultural preference, nutrition, or medicinal value.

In some regions, women manage household food storage, preservation, and preparation, ensuring year-round food security.

Cultural expectations can place women last in line for food in patriarchal societies, affecting their nutritional status.

These patterns reveal the interconnectedness of gender, culture, and power within food systems. Women’s decision-making authority can improve dietary diversity, especially when they control household income.

Regional Differences in Women’s Food-System Roles

Women’s roles vary across major world regions due to differing histories, technologies, and social structures.

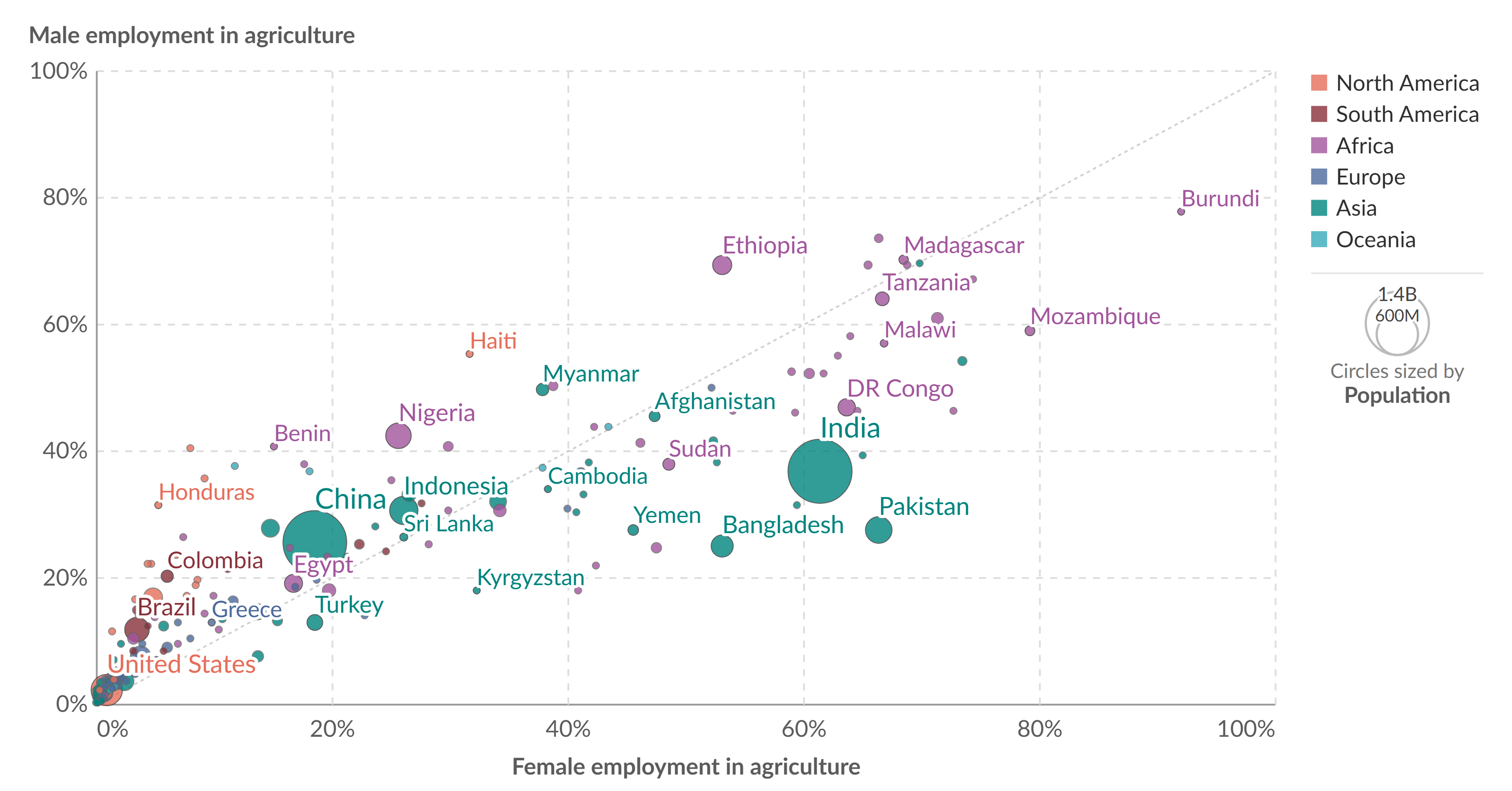

This chart compares the share of male and female employment in agriculture across countries, showing large regional differences in how heavily women depend on farm work. Countries toward the right have a larger share of employed women working in agriculture, while those toward the top have a larger share of employed men in agriculture. The graphic includes extra detail on male employment levels beyond the syllabus, but it helps illustrate how gendered agricultural roles differ by place and development level. Source.

Sub-Saharan Africa

Women account for a large share of agricultural labor and often manage small farms. However, limited access to land titles, technology, and credit constrains productivity. Female-headed households may rely heavily on communal networks and cooperative groups.

A female coffee farmer in Ethiopia works with coffee cherries on a small plot, representing women’s labor-intensive roles in smallholder agriculture. The scene reflects how women in Sub-Saharan Africa often manage crops critical for household consumption and regional markets. The image includes specific detail about coffee farming that is not required by the syllabus but offers a concrete example of women’s production work. Source.

South and Southeast Asia

In rice-based systems, women participate in transplanting, threshing, and processing. Green Revolution technologies increased yields but often reinforced gender inequalities because men received priority for training and resources.

Latin America

Women increasingly join agricultural cooperatives, gaining more control over production and marketing. Urban–rural migration patterns have left many women managing farms independently, a trend known as feminization of agriculture.

Feminization of Agriculture: A demographic trend in which women become the primary agricultural labor force as men migrate to cities for wage work.

Middle East and North Africa

Social norms can restrict women’s mobility and participation in public markets, though women frequently contribute to food processing and household cultivation of olives, grains, or vegetables.

Developed Regions

Mechanized and commercialized food systems create new opportunities in agribusiness, science, and supply-chain management. However, women remain underrepresented in land ownership and high-wage agricultural technology sectors.

Factors Driving Geographic Variation

Several key factors shape women’s roles across different food systems:

Cultural norms governing labor expectations and mobility

Access to land through inheritance or legal ownership

Technological change, which can expand or limit women’s participation

Market integration and the growth of global supply chains

Government policies affecting land rights, credit access, and employment protections

These drivers highlight why women’s roles are not uniform across regions or agricultural systems. Women’s contributions are essential to local, regional, and global food systems, yet their opportunities and constraints reflect deep geographic differences.

FAQ

Land ownership determines whether women can make independent choices about crops, investment, and land improvements. Without legal ownership, women may be excluded from credit schemes or technology programmes.

Secure land rights encourage longer-term planning, such as soil conservation, agroforestry, or investment in higher-value crops. This often improves household nutrition because women tend to allocate production towards food security rather than purely commercial outputs.

Women frequently manage seed selection, storage, and exchange, especially in subsistence farming communities. Their knowledge helps sustain local crop varieties adapted to microclimates.

Key contributions include:

Selecting seeds based on taste, cooking quality, or seasonal resilience

Preserving traditional varieties not prioritised by commercial markets

Participating in community seed networks that enhance biodiversity

These practices strengthen resilience against climate variability and market fluctuations.

Male out-migration often increases women’s responsibility for agricultural labour, farm management, and market activities. This shift can expand women’s autonomy but also increase workload.

Where remittances are reliable, women may gain resources for improved tools or inputs. In contrast, irregular income flows can intensify vulnerability, especially in regions where women lack legal authority to make major farm decisions.

Informal markets usually have low entry barriers, allowing women to trade small quantities of produce without licences, large capital, or formal infrastructure.

They offer:

Flexible hours compatible with household responsibilities

Social networks that provide credit, protection, or customer bases

Opportunities to reinvest earnings immediately into household needs

Formal markets, by contrast, require transportation, regulation compliance, and financial capital—barriers that disproportionately affect women.

Women’s tasks often rely on predictable rainfall, fertile soils, and seasonal cycles, making them highly sensitive to climate disruptions.

Impacts include:

Increased labour time for water or fuelwood collection

Reduced yields affecting women-managed crops

Shifts in market availability, influencing women’s trading activities

These pressures may deepen gender inequalities unless adaptation resources explicitly reach women farmers and traders.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one reason why women’s roles in food production vary between world regions.

Mark scheme

Award up to 3 marks:

1 mark for identifying a valid reason (e.g., cultural norms, access to land, or level of technological development).

1 mark for explaining how this factor shapes women’s participation in agriculture.

1 mark for providing a geographically relevant example (e.g., women’s high labour contribution in Sub-Saharan African smallholder farming versus more mechanised roles in developed regions).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Using specific examples, analyse how economic and social factors influence women’s roles in food distribution networks in different parts of the world.

Mark scheme

Award up to 6 marks:

1–2 marks for identifying relevant economic and/or social factors (e.g., informal market structures, cooperative membership, gender norms).

1–2 marks for explaining how each factor influences women’s participation in food distribution (e.g., informal markets enabling women to act as key intermediaries).

1–2 marks for integrating specific geographic examples from at least two regions (e.g., women dominating informal markets in West Africa; women’s role in Latin American agricultural cooperatives).