AP Syllabus focus:

‘The Green Revolution used high-yield seeds, increased chemical inputs, and mechanized farming to boost output.’

The Green Revolution dramatically transformed global agriculture through new technologies that increased crop yields, reshaped farming systems, and altered human-environment relationships across diverse regions during the mid-twentieth century.

Key Characteristics of the Green Revolution

The Green Revolution refers to a suite of innovations developed from the 1940s to the 1960s that boosted food production, primarily in developing countries. These technologies were designed to address widespread food shortages, especially in Asia and Latin America. Its defining features centered on high-yield varieties (HYVs) of staple crops, expanded use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides, and increased mechanization, all of which interacted to raise productivity.

High-Yield Seeds

The central innovation was the development of high-yield varieties (HYVs), especially for wheat, rice, and later maize. HYVs produced larger harvests under controlled conditions and responded strongly to fertilizer inputs.

Mature rice panicles developed and studied at the International Rice Research Institute illustrate the kind of high-yield varieties promoted during the Green Revolution. These HYV crops were bred to convert fertilizer and water into greater grain output, a central feature of Green Revolution technology packages. The image shows a specific rice cultivar rather than the full range of HYVs used globally, so it is a representative example rather than a complete catalogue. Source.

HYVs were engineered for traits such as dwarf stalks, which reduced lodging (falling over) in windy or rainy conditions, and shorter maturation periods that enabled multiple annual harvests. Their adoption required farmers to adjust planting routines and rely more heavily on external inputs. These seeds quickly spread through programs supported by institutions such as the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) and national agricultural ministries.

Following the initial introduction of HYV wheat in Mexico and India, additional varieties were adapted to local climates, helping countries increase overall grain production and reduce dependency on food imports.

Chemical Fertilizers and Pesticides

A second defining feature of the Green Revolution was the dramatic expansion of chemical fertilizer and pesticide use to support the needs of HYV crops. These inputs replaced many traditional soil-nutrient strategies and were necessary because HYVs extracted nutrients from soil at higher rates.

Chemical Fertilizer: A manufactured nutrient compound, typically containing nitrogen, phosphorus, or potassium, applied to soil to promote rapid plant growth and increase yields.

Pesticides limited crop loss by controlling insects, weeds, and diseases that could undermine productivity. Their systematic application enabled farmers to maintain the intensive cultivation cycles that HYVs required. The increased reliance on these chemicals reshaped agricultural landscapes, creating more uniform fields with fewer fallow periods.

Although chemical inputs improved output, they also raised concerns about soil degradation, water contamination, and human exposure to toxic substances. These effects would become major topics of debate in later assessments of the Green Revolution.

Mechanization and Irrigation Expansion

Many farmers adopted new tools and machines to support the intensified cultivation enabled by HYVs. Mechanization included tractors, harvesters, and mechanical pumps, all of which reduced labor needs and allowed for quicker planting and harvesting cycles. Mechanization also made large-scale monocropping more feasible.

Mechanization: The use of machinery to perform agricultural tasks such as plowing, planting, and harvesting, reducing manual labor and increasing efficiency.

Mechanization worked hand-in-hand with expanded irrigation infrastructure. HYVs required regular and predictable water supplies, so regions that invested in canals, tube wells, and pump systems experienced the greatest yield increases. India’s Green Revolution, for example, was concentrated in states with reliable water and electricity for pump operation, such as Punjab and Haryana.

These technologies collectively raised carrying capacity—the amount of population a region’s agricultural system can support—though outcomes varied based on environmental and economic factors.

Changes in Farming Systems

The Green Revolution shifted agricultural practices from traditional subsistence systems to more commercially oriented production. Farmers increasingly specialized in a small number of high-value cereal crops rather than maintaining diverse, mixed-crop fields. This specialization increased dependence on global seed companies and agricultural input suppliers.

Key farming system changes included:

Monocropping, with large fields dedicated to a single HYV crop.

Decreased fallow periods, as HYVs matured quickly and encouraged multiple cropping cycles.

Greater capital intensity, since farmers required money for seeds, fertilizer, irrigation, and machinery.

Reduced labor needs, which contributed to rural-to-urban migration in some regions.

These structural shifts aligned with broader economic development goals, linking rural agriculture with national markets and industrial growth.

Geographic Reach

The Green Revolution most strongly affected Asia and Latin America, particularly countries with government support for agricultural modernization. India, Pakistan, Mexico, and the Philippines saw major gains in wheat and rice production.

Rice farmers in the Philippines work in irrigated paddy fields that reflect the intensified cultivation associated with Green Revolution technologies. The scene highlights how HYV seeds, fertilizers, and improved water control were implemented on the ground by farmers in key Asian countries. The image also shows rice straw being incorporated as organic matter, a management detail not specifically required by the syllabus but consistent with field practices in these regions. Source.

In contrast, much of Sub-Saharan Africa adopted fewer Green Revolution technologies due to variable climates, limited infrastructure, and reduced investment.

The overall outcome was substantial global growth in cereal production, accompanied by greater regional disparities in agricultural capacity.

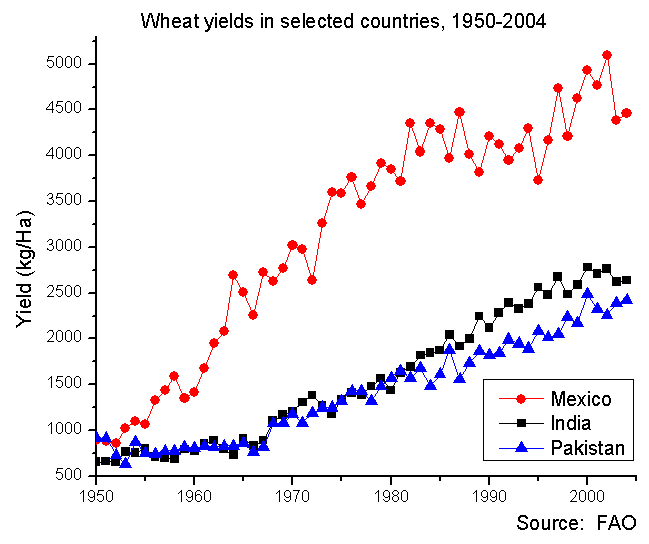

This graph shows rising wheat yields in selected countries from 1951 to 2004, reflecting the impact of Green Revolution technologies on cereal output. The increasing lines correspond to the widespread adoption of high-yield varieties, chemical fertilizers, and improved irrigation systems in many regions. The figure includes detailed country-by-country data and a long time span, which go beyond the AP Human Geography syllabus but provide helpful visual evidence of how the Green Revolution boosted production. Source.

FAQ

Adoption depended heavily on whether regions had the necessary infrastructure, including reliable irrigation systems, access to fertilisers, and transport networks to distribute inputs.

Governments also played a major role: countries such as India and Mexico invested in agricultural extension services, credit schemes, and seed distribution, which enabled rapid uptake. Social factors, including landholding size and farmers’ ability to take financial risks, further shaped where HYV packages could be implemented effectively.

Wheat and rice were chosen because they were staple foods for large populations in Asia and Latin America, where food shortages were most severe.

These crops also responded well to selective breeding techniques and produced clear yield improvements under controlled conditions. Their importance to national food security made them priority targets for international research institutions.

The development of HYVs shifted seed production from local, farmer-saved varieties to commercially distributed seed systems.

This encouraged the rise of national and international seed industries that produced patented or tightly managed varieties. As a result, farmers increasingly relied on annual seed purchases rather than traditional seed-saving practices, reinforcing commercialisation in agriculture.

Institutions such as the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) and the International Rice Research Institute (IRRI) developed new seed varieties and trained agronomists from developing countries.

These organisations facilitated technology transfer by conducting field trials, sharing germplasm, and supporting national research centres. Their networks enabled the rapid diffusion of improved crop strains across regions facing food insecurity.

HYVs encouraged monocropping and the replacement of diverse traditional varieties with a smaller number of genetically uniform crops.

This led to reduced on-farm genetic diversity, making agricultural systems more vulnerable to pests, diseases, and environmental stress. Although this loss was not always visible immediately, it raised long-term concerns about resilience and ecological stability.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which high-yield varieties (HYVs) contributed to increased agricultural productivity during the Green Revolution.

Mark scheme

Award up to 3 marks:

1 mark for identifying a valid contribution of HYVs (e.g., higher yields, shorter growing seasons, resistance to lodging).

1 mark for explaining how this characteristic increased productivity (e.g., allowed more harvests per year, produced more grain per plant).

1 mark for a clear link to overall agricultural output (e.g., enabling countries to reduce food shortages or increase cereal production).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Discuss the role of chemical inputs and mechanisation in transforming agricultural practices during the Green Revolution. Refer to both benefits and potential drawbacks.

Mark scheme

Award up to 6 marks:

1–2 marks for describing the use of chemical fertilisers and pesticides (e.g., supplying nutrients, reducing pest losses).

1–2 marks for explaining how mechanisation changed farming (e.g., faster planting and harvesting, reduced labour needs, enabling large-scale cultivation).

1 mark for outlining at least one benefit (e.g., increased yields, more reliable production).

1 mark for outlining at least one drawback (e.g., environmental damage, soil degradation, increased dependency on purchased inputs).