AP Syllabus focus:

‘The Green Revolution created both positive and negative consequences for human populations and the environment.’

The Green Revolution dramatically reshaped global agriculture, raising yields while creating significant human and environmental impacts that continue to influence farming practices, rural livelihoods, and ecological conditions worldwide.

Human Consequences of the Green Revolution

The Green Revolution’s reliance on high-yielding varieties (HYVs), synthetic fertilizers, pesticides, and mechanization transformed food production but also reshaped demographics, nutrition, and economic opportunities.

Improvements in Food Availability and Nutrition

Increased grain yields—especially wheat and rice—expanded national food supplies in countries such as India and Mexico.

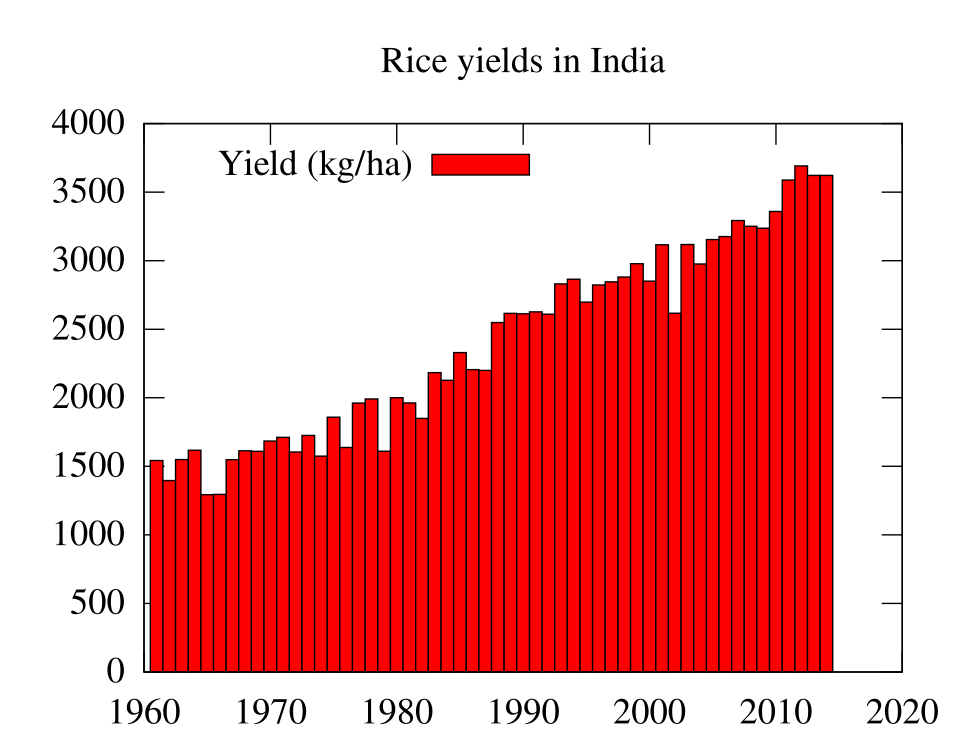

Rice yields in India have risen sharply since the 1960s, reflecting the adoption of high-yielding varieties, fertilizers, and irrigation. This trend illustrates how the Green Revolution converted technological innovation into higher food production and improved food security. The image includes more detailed annual data than required by the syllabus but remains directly relevant to the concept. Source.

More reliable harvests reduced famine risk and contributed to population growth in regions where food scarcity previously limited survival rates.

Enhanced calorie availability allowed many households to access more consistent diets.

Uneven Social and Economic Benefits

While the Green Revolution increased total food production, its benefits were distributed unevenly.

Farmers with capital could purchase HYV seeds and chemicals, expanding production and reinforcing agrarian inequality.

Smallholders without access to credit often struggled to afford required inputs, limiting their ability to compete.

Rural wage laborers sometimes benefited from greater agricultural activity, but mechanization reduced the need for manual labor in some regions.

Market dependence increased as farmers relied more heavily on purchased inputs rather than traditional seed-saving practices.

Gendered Effects on Agricultural Roles

Women in many rural societies experienced shifting roles as Green Revolution technologies spread.

In some areas, mechanization reduced women’s involvement in planting or threshing.

In other regions, labor burdens increased when men migrated to cities and women were left to manage farms dependent on HYV inputs.

Access to agricultural credit often favored men, further exacerbating gender disparities.

Environmental Consequences of the Green Revolution

Although the Green Revolution raised agricultural productivity, its heavy reliance on chemical inputs and resource-intensive methods created long-term environmental challenges.

Soil Degradation and Chemical Dependency

The push to maximize yields led to widespread use of nitrogen fertilizers, pesticides, and herbicides.

Soil degradation: The decline in soil’s physical, biological, or chemical quality due to intensive land use and input-heavy farming.

Overapplication of fertilizers damaged soil fertility and altered nutrient balances such as nitrogen and phosphorus levels.

Pesticide overuse reduced biodiversity, harmed beneficial insects, and created chemical-resistant pest populations.

Soil acidification and nutrient leaching became common in areas with repeated monocropping.

A normal sentence appears here to comply with formatting guidelines and clearly transition to new material.

Water Use, Irrigation Stress, and Pollution

HYVs typically require abundant water, leading to significant hydrological impacts.

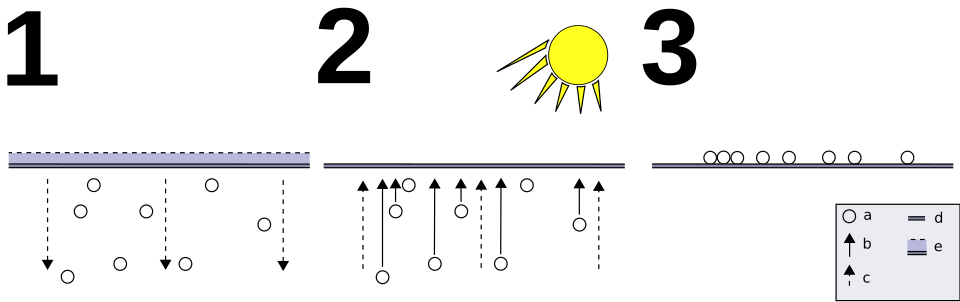

This diagram shows how repeated irrigation draws dissolved salts upward, where they accumulate and damage crops. It directly illustrates the process of soil salinization associated with intensive irrigation in Green Revolution regions. The labeled zones and arrows add detail beyond the syllabus but reinforce the key environmental process. Source.

Heavy irrigation accelerated aquifer depletion, especially in regions such as northern India and the North China Plain.

Waterlogging and salinization occurred when poor drainage systems allowed salts to accumulate in the soil.

Runoff containing fertilizers and agrochemicals polluted rivers, lakes, and groundwater, contributing to algal blooms and degraded water quality.

Biodiversity Loss and Monocropping

Green Revolution strategies emphasized large-scale monoculture.

Monocropping: The agricultural practice of growing a single crop species repeatedly on the same land.

Monocropping reduced genetic diversity in crop species, increasing vulnerability to disease and climate stress.

Traditional seed varieties declined as HYVs spread, decreasing local adaptation and resilience.

Agricultural landscapes became simplified, reducing wildlife habitats and diminishing overall ecosystem health.

A normal sentence appears here to maintain the required separation between definition blocks and narrative explanation.

Long-Term Sustainability Challenges

As Green Revolution methods expanded, questions arose about long-term environmental and economic sustainability.

Energy and Input Intensity

HYVs often depend on high external inputs such as fuel for machinery, processed fertilizers, and commercially manufactured pesticides.

Energy-intensive farming increased greenhouse gas emissions from fertilizer production and mechanized operations.

Land and Resource Pressures

Continuous cultivation placed pressure on marginal lands, accelerating erosion and degrading ecosystems.

Increased irrigation demands strained river systems and groundwater reserves in semi-arid and arid regions.

Chemical accumulation in soils created persistent contaminants harmful to crops and human health.

Socioeconomic Vulnerability

Communities became increasingly exposed to fluctuations in global input prices.

Rising fertilizer and seed costs made farmers dependent on external markets and multinational agribusiness companies.

Crop failures involving HYVs—often less resilient to drought or pests—created severe economic stress for farmers who had invested heavily in purchased inputs.

Interconnected Human–Environment Impacts

Human and environmental consequences of the Green Revolution are deeply intertwined.

Social inequalities often intensified when environmental degradation reduced productivity for those least able to adopt newer technologies.

Health risks increased in areas where farmers and communities were exposed to toxic agrochemicals.

Long-term agricultural resilience was undermined where ecosystems were stressed beyond their capacity.

Toward More Sustainable Approaches

Although the Green Revolution achieved its goal of boosting yields, recognition of its human and environmental consequences has shaped modern agricultural debates.

Shifts Toward Alternative Practices

Integrated pest management, organic farming, and conservation agriculture emerged as attempts to reduce chemical dependence.

Policymakers and scientists now emphasize sustainability, equity, and resilience to balance productivity with environmental stewardship.

The legacy of the Green Revolution continues to influence contemporary discussions of food security, environmental protection, and community wellbeing.

FAQ

Farmers shifted from locally sourced inputs to externally purchased ones, including hybrid seeds, synthetic fertilisers, and industrial pesticides.

This created long-term dependence on commercial suppliers and reduced traditional practices such as seed saving and organic soil management.

Environmental impacts varied because regions differed in water availability, soil structure, and local capacity to manage inputs.

Areas with fragile soils, limited drainage, or over-extracted aquifers—such as semi-arid zones—were more vulnerable to salinisation, waterlogging, and depletion.

Mechanisation and rising input costs reduced demand for agricultural labour in some areas, pushing workers towards urban centres.

Where yields rose significantly, some regions saw temporary in-migration for seasonal work, but these gains often declined as machines replaced manual labour.

Pesticides reduced populations of pollinators, natural predators, and soil microorganisms.

Over time this weakened ecosystem resilience, making farms more vulnerable to pest outbreaks and reducing biodiversity in surrounding habitats.

Governments often expanded subsidy programmes, irrigation schemes, and extension services to promote high-yield farming.

This increased interaction between farmers and state agencies but also created tensions when policies led to unequal access to credit, water, or technological support.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which the Green Revolution created an environmental challenge for agricultural regions.

Mark scheme

Award up to 3 marks:

1 mark for identifying a relevant environmental challenge (e.g., soil salinisation, groundwater depletion, biodiversity loss).

1 mark for describing how Green Revolution practices contributed to this challenge (e.g., intensive irrigation causing salt build-up).

1 mark for explaining a consequence of the challenge (e.g., reduced soil fertility or lower crop yields).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Assess how the Green Revolution produced both positive and negative consequences for human populations.

Mark scheme

Award up to 6 marks:

1–2 marks for describing positive impacts (e.g., higher crop yields, reduced famine risk, improved food security).

1–2 marks for describing negative human impacts (e.g., increased inequality, dependence on purchased inputs, displacement through mechanisation).

1–2 marks for assessment, such as:

showing a balanced argument

explaining variation between regions or social groups

linking outcomes to specific Green Revolution technologies (HYV seeds, fertilisers, irrigation)