AP Syllabus focus:

‘Specialty farming regions do not always follow von Thünen’s concentric-ring pattern.’

Real-world farming rarely matches von Thünen’s predicted land-use rings because complex economic, technological, environmental, and political factors modify agricultural patterns and farmer decision-making.

Factors That Distort the Von Thünen Model

Physical Environment and Landscape Constraints

The von Thünen model assumes uniform physical conditions, but real landscapes contain significant variation.

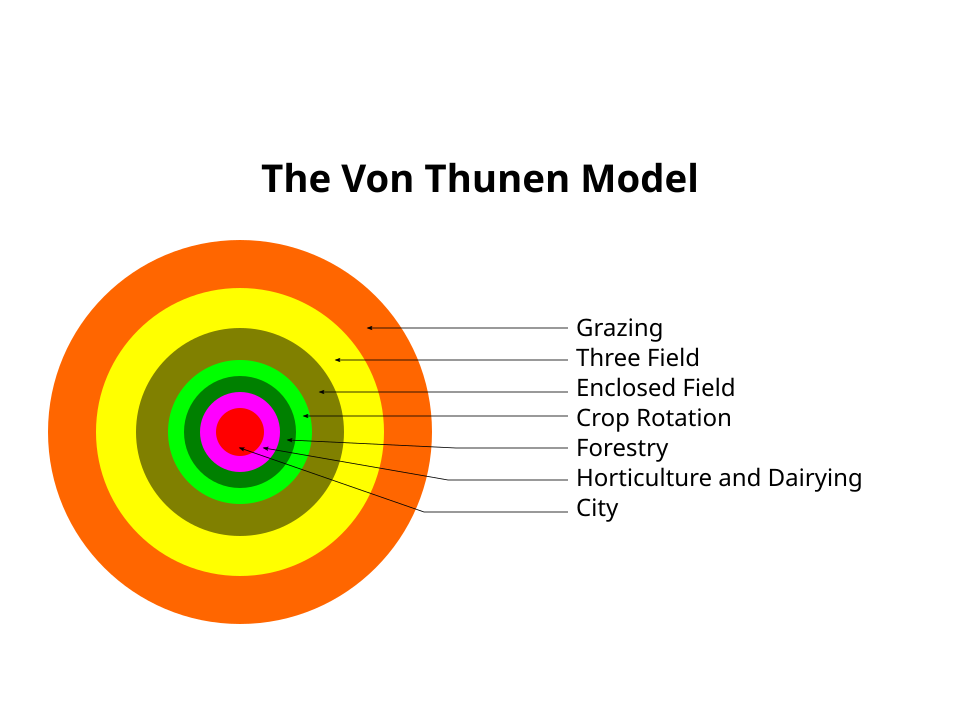

Diagram of von Thünen’s idealized concentric land-use rings surrounding a central city and market. It shows how intensive farming, forests, crops, and ranching are arranged by distance in the classical model. The ring labels provide specific examples of land uses without adding concepts beyond those discussed in the notes. Source.

Differences in topography, soil fertility, water availability, and climate reshape agricultural choices.

Steep slopes increase production and transport difficulties, pushing farmers to cultivate only certain crops.

Irregular rivers, wetlands, and mountain barriers can interrupt ring patterns and redirect transport routes.

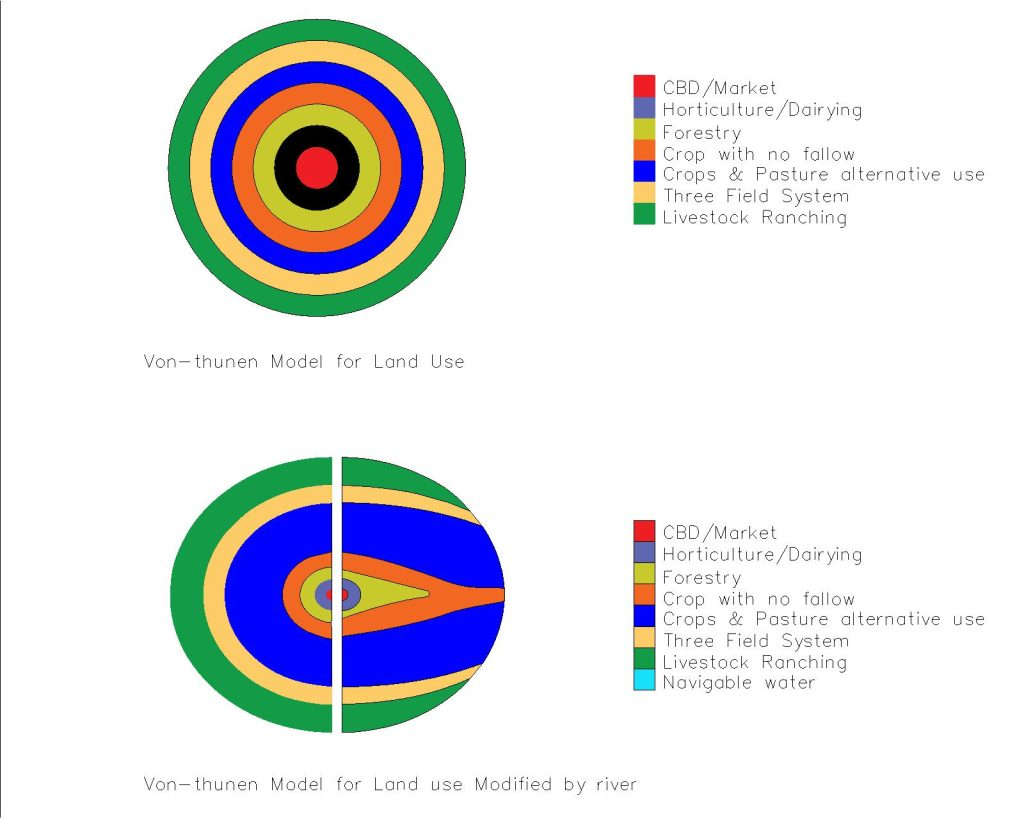

Comparative diagrams of von Thünen’s model showing ideal conditions and a modified version influenced by a river. The second diagram demonstrates how rings stretch and bend along the river corridor due to cheaper water transportation. The added detail reinforces how real environments disrupt the model’s symmetry. Source.

Fertile river valleys may attract intensive agriculture even if they lie far beyond the zone predicted by the model.

Because location‐based decisions depend partly on ecological suitability, farmers prioritize land that supports their crop or livestock system rather than adhering to concentric distance rings.

Satellite montage of agricultural patterns showing global variation in field geometries and scales. The mosaic illustrates how real farming landscapes form irregular circles, grids, and patchworks shaped by irrigation, terrain, and land tenure rather than perfect rings. Additional visual detail about cropping intensity supports the concept that real landscapes diverge from von Thünen’s ideal. Source.

Urban Influence Beyond a Single Market

Von Thünen’s theory assumes one isolated market center, yet modern agriculture operates within multi-nodal urban networks. Multiple nearby cities alter pricing, demand, and accessibility.

Competing urban markets create overlapping zones of production, distorting neat ring shapes.

Farmers may orient production toward the closest or most profitable urban center, not necessarily the largest or the nearest.

Expanding metropolitan regions introduce urban sprawl, raising land costs unevenly and shifting agricultural zones outward.

These complex urban connections fundamentally disrupt the model’s assumption of a single, dominant market.

Transportation Technology and Infrastructure

The original model relied on horse-drawn carts and slow overland movement. With modern transport innovations, distance exerts less control over land use.

Transportation Technology: The set of tools, vehicles, and infrastructure that affect how quickly and cheaply goods can move across space.

Farmers can send perishable or bulky goods farther from markets thanks to:

Highway networks and paved roads

Refrigerated trucks and cold-chain logistics

Railways, inland ports, and air freight

Global shipping routes linking agricultural exporters with distant consumers

Because transportation costs decline and mobility increases, distance from markets no longer determines crop choice as rigidly as the model proposes.

Government Policies and Political Decision-Making

Political intervention can strongly influence farming location, leading to patterns that do not resemble von Thünen’s rings.

Subsidies encourage specific crops regardless of market distance.

Zoning laws restrict or permit agriculture in particular areas.

Protected lands (national parks, conservation areas) prevent agriculture where the model might predict it.

Trade regulations alter profitability in ways the model does not anticipate.

Policies shift economic incentives, often overriding spatial logic.

Globalization and International Markets

The von Thünen model is based on a locally self-sufficient economy, yet contemporary agriculture is embedded within global commodity chains.

Farmers may produce for international export rather than for the nearest urban center.

Global price fluctuations drive crop choices based on profit maximization, not local demand.

Long-distance shipping allows crops such as soybeans, palm oil, and coffee to be cultivated far from a consuming region.

Global economic integration makes agricultural activity less dependent on immediate proximity to markets.

Advances in Agricultural Technology

Modern technology increases yields, enhances land productivity, and reduces natural risk, contributing to deviations from concentric patterns.

Irrigation allows intensive agriculture in arid regions far from cities.

Genetically modified seeds and improved fertilizers expand feasible crop locations.

Mechanization reduces dependence on labor availability, enabling intensive farming in remote or sparsely populated regions.

These innovations weaken the direct link between land quality, distance, and agricultural land use assumed by the model.

Cultural Preferences and Historical Patterns

Cultural and historical traditions shape farming choices in ways the model does not predict.

Long-established agricultural communities may continue raising specific crops or livestock due to heritage, knowledge systems, or identity.

Certain specialty crops, such as wine grapes or olives, cluster in culturally valued regions regardless of distance to markets.

Historical landholdings and property boundaries persist, limiting the idealized circular patterns envisioned by the model.

Cultural landscapes therefore add complexity to agricultural spatial patterns.

Market Specialization and Niche Production

Specialty farming often contradicts the general economic assumptions of the model.

Viticulture, orchards, and organic farming locate in areas with environmental or branding advantages rather than dictated by distance.

Value-added agriculture (such as artisanal cheeses or specialty vegetables) may thrive near tourism routes or high-income suburban markets.

Farmers producing niche goods may choose locations based on prestige, terroir, or contractual arrangements.

These decisions are profit-driven but not tied to concentric zones.

Environmental Regulations and Sustainability Considerations

Contemporary agriculture is increasingly shaped by environmental awareness. Regulations may restrict land uses where the model might place intensive production.

Limits on fertilizers or pesticides reduce agricultural intensity in sensitive areas.

Conservation programs pay farmers to leave land fallow.

Buffer zones near waterways restrict livestock or crop operations.

Sustainability concerns impose spatial constraints beyond economic cost–distance relationships.

Summary of Why the Model Does Not Fit

Real-world farming diverges from von Thünen’s rings because environmental variation, urban complexity, modern transportation, government policies, globalization, technology, cultural factors, market specialization, and environmental regulations all reshape agricultural land-use patterns beyond what the model’s simplified assumptions can capture.

FAQ

Rail lines and motorways channel movement along specific routes rather than evenly in all directions, concentrating agricultural activity near these corridors.

This creates elongated or clustered zones of production shaped by accessibility to transport nodes rather than distance to a central market.

Areas lacking transport connections may become marginal agricultural zones even if they lie close to a city.

Perishable-goods supply chains prioritise reliable cold storage, distribution hubs, and rapid logistics over pure geographic proximity.

Producers often locate near processing facilities, distribution centres, or motorway junctions instead of following distance-based patterns.

Specialised storage requirements also allow some producers to operate farther from markets without sacrificing freshness or profitability.

Labour varies widely across space, and farmers often choose locations where seasonal or low-cost labour is accessible.

This can shift intensive agriculture towards regions with affordable farmworkers, even if these regions lie farther from urban centres.

High-wage peri-urban areas may push labour-intensive farming away despite being near markets.

Some agricultural products are tied to place-based identity, making location part of the product’s value.

Producers may cluster in culturally recognised regions to maintain authenticity, tourist appeal, or certification labels.

Examples include heritage cheeses, premium wines, or regionally branded horticulture.

Historic land divisions, inheritance patterns, and long-standing property rights result in irregular patchworks of ownership.

Farmers cannot easily relocate to form neat rings because boundaries restrict movement and consolidation.

Land parcels may be fragmented, elongated, or shaped by past political decisions, giving rise to spatial patterns that diverge from theoretical predictions.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one reason why real-world agricultural patterns often do not display the concentric rings predicted by the von Thünen model.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for a basic statement.

2 marks for a developed point.

3 marks for a fully explained point with reference to real-world conditions.

Acceptable points include:

Transport technology reduces the effect of distance on land use (1 mark).

Explanation that modern transport allows perishable goods to travel far from markets, weakening the expected ring pattern (2–3 marks).

OR

Physical landscape varies and is not uniform (1 mark).

Explanation that factors such as rivers, mountains, or fertile valleys redirect land use away from the model’s ideal rings (2–3 marks).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Using examples, analyse two factors that cause agricultural land-use patterns to deviate from the classic von Thünen model.

Mark scheme:

1–2 marks: Identifies two appropriate factors (e.g., government policy, global markets, technological change, environmental constraints).

3–4 marks: Provides explanation of how each factor alters land-use patterns away from concentric rings.

5–6 marks: Provides detailed analysis with clear real-world or conceptual examples demonstrating how these factors disrupt the assumptions of the model.

Examples of acceptable points:

Government subsidies may encourage farmers to grow specific crops regardless of distance from the market (identification 1 mark; explanation 2 marks; illustrative example such as US maize subsidies 1 mark).

Global trade enables production aimed at international markets rather than a single local city, breaking the isolated market assumption (identification 1 mark; explanation 2 marks; example such as export-oriented coffee farming 1 mark).

Physical environment such as mountain ranges, rivers, or areas of high soil fertility disrupts circular land-use patterns (identification 1 mark; explanation 2 marks; relevant example 1 mark).