AP Syllabus focus:

‘Food and other agricultural products move through global supply chains that link producers and consumers.’

Global agricultural supply chains connect farmers, processors, distributors, and consumers across international networks, shaping how food is produced, transported, marketed, and accessed in an increasingly interdependent world economy.

Global Agricultural Supply Chains

Global agricultural supply chains refer to the networked processes that move agricultural goods from production to consumption across international borders. These chains illustrate how distant producers and consumers become linked through trade, transportation systems, and economic relationships. They also reveal how political decisions, corporate strategies, and technological advances determine what food is available, where it comes from, and how it is priced. Because the AP specification emphasizes the connection between producers and consumers, understanding the steps and actors involved in these chains is essential.

Key Components of Supply Chains

The movement of agricultural products involves multiple stages, each shaped by economic systems, infrastructure, and global demand.

Input supply: Seeds, fertilizers, machinery, and labor that enable productive farming. Input suppliers may be small regional firms or large global corporations.

Primary production: Farmers cultivate crops or raise livestock based on climate, available resources, and market incentives.

Processing: Raw agricultural goods are transformed into more valuable products, such as turning wheat into flour or cocoa into chocolate.

Packaging: Goods are prepared for distribution using standardized materials and labeling that meet regulatory requirements.

Transportation and logistics: Products move by road, rail, ship, or air. This stage involves coordinating routes, storage, and timing to maintain quality and minimize costs.

Distribution centers and wholesalers: Products are aggregated, sorted, and sent toward retail or industrial buyers.

Retail and consumption: Goods reach consumers through supermarkets, small shops, farmers’ markets, or online delivery systems.

These stages highlight how supply chains rely on both global integration and local-scale decisions.

This diagram shows key elements of a local and regional food system, from production and distribution to marketing, purchasing, and consumption. It also includes resource and waste recovery, which goes slightly beyond the AP Human Geography syllabus but helps students see how food systems connect production with environmental impacts. The circular layout emphasizes that agricultural supply chains are continuous and interconnected rather than a simple linear path. Source.

Linking Producers and Consumers

The defining feature of global agricultural supply chains is the direct and indirect connection between production regions and consumption markets. This relationship is reinforced by international trade, corporate networks, and evolving consumer preferences.

Producer–consumer linkages: The economic and spatial relationships that connect agricultural producers with buyers and final consumers, often across long distances.

Agricultural products frequently travel thousands of miles before reaching consumers, creating what geographers call “spatially stretched” food networks. This spatial extension requires coordination and communication across jurisdictions, languages, and regulatory environments.

One important consequence of these linkages is the commodification of food, meaning agricultural goods are treated primarily as economic products valued for global market exchange. Commodification encourages standardized production and efficiency, but it can also distance consumers from the environmental and social origins of their food.

Globalization and Supply Chain Organization

Modern supply chains are shaped heavily by globalization. Corporations with multinational reach manage contracting, production, processing, and distribution across several continents. Retail giants play an especially important role because they set standards that influence farmers’ decisions.

Key organizational structures include:

Vertical integration: When one corporation controls multiple stages of the supply chain, from production to retail.

Contract farming: Farmers enter agreements to produce specific quantities or qualities for agribusiness companies, often receiving inputs or technical guidance.

Global sourcing: Firms search worldwide for the lowest production costs, most efficient logistics, or highest-quality products.

These structures reinforce a system in which decisions in one part of the chain ripple across others.

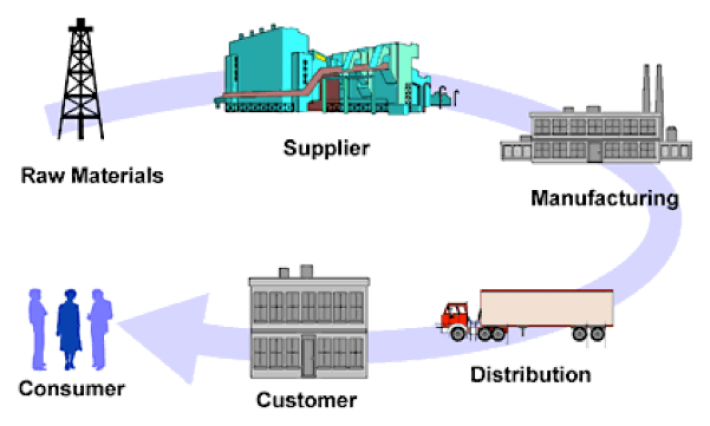

This illustration presents a simplified supply chain moving from raw materials through suppliers, manufacturing, distribution, and customers to the final consumer. While the example is generic rather than agriculture-specific, students can easily map farms into the “raw materials” stage and food processors, distributors, and retailers into later stages. The image clarifies how each node depends on the others, supporting the idea of interconnected global commodity chains. Source.

Transportation, Technology, and Quality Control

Transportation improvements have made long-distance agricultural trade faster, cheaper, and more reliable. Refrigerated shipping, sealed containers, and advanced logistics allow perishable items such as berries, seafood, and flowers to reach global markets.

This photograph shows the container ship MSC Sindy loaded with thousands of standardized containers, some of which are refrigerated for perishable goods. Large vessels like this are central to global agricultural supply chains, carrying grains, fruits, meats, and processed foods between world regions. The port cranes and infrastructure visible in the image reflect additional logistical steps that help illustrate how global trade physically operates. Source.

Digital tools also streamline operations. Satellite tracking, data analytics, and automated inventory systems increase efficiency and reduce waste. These tools support traceability, the ability to follow a product’s path through the chain for safety, quality, or marketing purposes.

Cold chain: A temperature-controlled supply system that preserves perishable products during storage and transport.

After applying these technologies, firms can monitor spoilage risks, optimize routing, and coordinate delivery windows. Traceability has become especially important as consumers demand transparency about environmental impacts, labor conditions, and production methods.

Economic and Political Influences

Global agricultural supply chains do not operate in a vacuum. They are shaped by:

Trade agreements and tariffs that determine which products move freely and which face restrictions.

National regulations, including food safety rules, labor laws, and environmental policies.

Subsidies that influence what farmers grow and how competitively they can export.

Infrastructure quality, particularly ports, highways, warehouses, and communication systems.

Geopolitical relationships, which can strengthen or weaken trade routes.

These factors can either strengthen connections between producers and consumers or disrupt them entirely.

Environmental and Social Dimensions

Global supply chains affect landscapes, labor markets, and cultural practices. They can promote economic growth and market access for farmers, but they may also create environmental pressure through resource-intensive production. Social impacts appear in the form of labor conditions, gender roles within agriculture, and the economic vulnerability of producers dependent on volatile global markets.

Why Supply Chains Matter in Human Geography

Understanding global agricultural supply chains helps explain:

Uneven economic development

Global trade patterns

Regional specialization in crops and livestock

Environmental impacts of commercial agriculture

How consumers shape agricultural production through preferences

Through these complex networks, agricultural goods move from fields to households worldwide, linking people, places, and economies across vast distances.

FAQ

Multinational agribusinesses often control large segments of the supply chain, giving them significant leverage over pricing, quality standards, and sourcing decisions.

They may influence:

What crops are grown and where

Contract terms for farmers

Global distribution routes and partnerships

This consolidation of power can weaken bargaining positions for small-scale farmers while strengthening the influence of firms that manage processing, logistics, and retail.

Major nodes often emerge where economic, infrastructural, and political advantages converge.

Key factors include:

Access to deep-water ports and efficient transport networks

Strong regulatory frameworks and quality control systems

Access to cold storage and large-scale processing facilities

Stable trade relationships and low tariff barriers

Established logistics and finance industries

Countries with these assets become preferred hubs for aggregation, processing, or global distribution.

Supply chains typically pivot by sourcing from alternative producing regions, often those with similar climates or established export capacity.

Responses may involve:

Increasing reliance on inventories and buffer stocks

Diversifying sourcing to multiple regions

Adjusting shipping routes to access alternative suppliers

Such disruptions can temporarily raise global prices, redistribute trade flows, and expose vulnerabilities in highly specialised production systems.

Supply chain complexity varies based on perishability, processing requirements, and regulatory oversight.

More complex chains typically involve:

Highly perishable goods such as berries or seafood

Products requiring multi-stage processing or strict temperature control

Goods subject to tight international safety and quality regulations

Staple crops like grains require simpler, more standardised handling, while fresh or highly regulated items need layered logistical systems.

Growing demand for ethically sourced or environmentally sustainable goods encourages firms to adjust sourcing patterns, invest in traceability, and modify processing or distribution methods.

This often leads to:

Certification schemes such as Fairtrade or organic verification

Greater transparency requirements across all chain stages

Pressure on producers to adopt greener or more socially responsible practices

Retailers may prioritise suppliers who meet these standards, shifting market power toward more sustainable producers.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain how global agricultural supply chains connect producers to consumers.

Question 1

1 mark: Basic statement that producers and consumers are linked through the movement of agricultural goods.

2 marks: Clear explanation that goods pass through multiple stages such as processing, packaging, and distribution.

3 marks: Detailed explanation including the idea that international trade and corporate networks physically and economically connect distant production regions with consumer markets.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Analyse two ways in which improvements in transportation and logistics have influenced the spatial organisation of global agricultural supply chains.

Question 2

1 mark: Identifies an improvement such as refrigerated shipping, containerisation, or advanced routing technology.

2 marks: Identifies a second improvement.

3–4 marks: Explains how these improvements allow perishable goods to travel longer distances, increasing global reach and enabling new trade flows.

5–6 marks: Analyses consequences for spatial organisation, such as increased geographical specialisation of production, reduced importance of distance from markets, and the creation of extensive long-distance trade networks.