AP Syllabus focus:

‘Food distribution networks are shaped by political relationships, infrastructure, and patterns of world trade.’

Food distribution networks link producers to consumers across space, and their efficiency depends on political stability, transportation systems, and global economic interactions shaping how food moves worldwide.

Food Distribution Networks

Food distribution networks refer to the interconnected systems that move food from the site of production to places of processing, distribution, retail, and consumption. These networks vary in scale from local supply chains to globalized commercial trade routes, and they are shaped by the geographic, political, and economic contexts through which agricultural goods flow.

Key Components of Food Distribution Networks

Food distribution networks operate through several interconnected stages that influence how quickly and affordably food reaches consumers.

Production zones where crops and livestock are grown or raised.

Processing centers that convert raw agricultural goods into market-ready products.

Transportation routes including roads, railways, shipping lanes, and air freight.

Wholesale and retail systems, ranging from global commodity exchanges to local markets.

Consumers, whose locations and purchasing power affect demand.

When discussing these components, geographers use the term supply chain to describe the full sequence of activities connecting producers and consumers.

Diagram of key food system elements, including food production, distribution and aggregation, processing, marketing, purchasing, preparation and consumption, and resource and waste recovery. It visually reinforces the idea of a multi-stage supply chain linking producers and consumers. The diagram contains additional elements beyond the AP syllabus, such as waste recovery, but still supports understanding of food distribution networks. Source.

Supply Chain: The network of people, activities, technologies, and resources involved in moving a product from production to consumption.

Food distribution networks differ dramatically across regions because they reflect available infrastructure, state investment, cultural food preferences, and integration into global markets.

Infrastructure and Spatial Efficiency

Infrastructure is one of the most critical determinants of distribution efficiency because it affects transportation speed, transportation costs, and reliability. Regions with extensive highway systems, deepwater ports, rail corridors, and cold-storage facilities typically have lower losses and greater ability to move perishable goods long distances.

Cold-chain logistics maintain temperature control throughout transport, expanding trade in fruits, vegetables, meat, and dairy.

Port capacity determines how rapidly bulk agricultural goods like grain or soybeans can be exported.

Aerial view of the Port of San Juan in Puerto Rico, illustrating how container yards and deepwater berths facilitate large-scale cargo movement. The port infrastructure shown here also supports agricultural shipments, including refrigerated containers. While the image depicts general freight rather than only food cargo, the same infrastructure underpins global food distribution networks. Source.

Rural road quality influences the ability of small farmers to participate in national or international markets.

Limited or deteriorating infrastructure increases spoilage, raises prices, and can contribute to national food insecurity.

Global Trade Patterns in Food Distribution

Food distribution networks today are heavily shaped by global trade systems. Modern agriculture depends on the worldwide exchange of commodities, technological inputs, and manufactured food products. The rise of containerized shipping and multinational agribusinesses has allowed food to travel farther and more efficiently than ever before.

Drivers of Global Food Trade

The structure of global food trade reflects a combination of environmental, political, and economic forces:

Comparative advantage, meaning countries export crops best suited to their climate and import goods they cannot efficiently produce.

Political stability, which encourages foreign investment and long-term trade agreements.

Trade blocs such as the European Union or USMCA, which reduce tariffs and streamline cross-border movement.

Global demand, shaped by population size, dietary transitions, and income levels.

Corporate influence, as transnational companies coordinate production and distribution across multiple continents.

Because of these factors, food grown in one hemisphere is routinely consumed in another, contributing to strongly interconnected global markets.

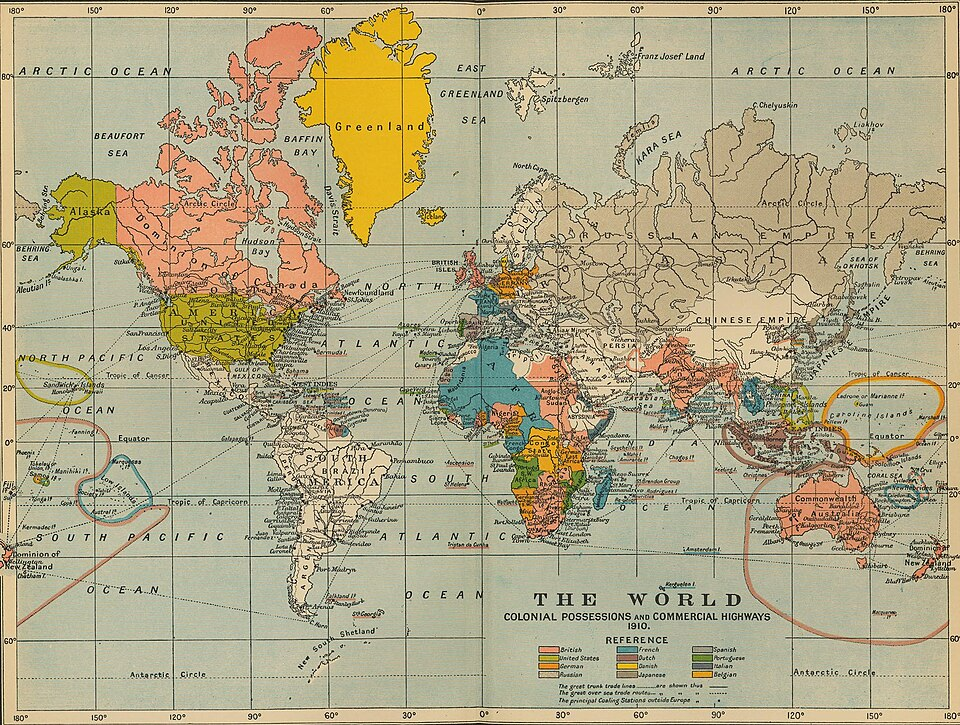

Historical map showing colonial territories and the major sea routes linking them in 1910, illustrating how long-distance commercial corridors structured global trade. The shipping lanes reveal concentrated pathways that connected distant markets. The map includes broader imperial and historical details not required by the AP syllabus, but the trade routes directly support understanding of global distribution networks. Source.

Comparative Advantage: The ability of a region or country to produce a good at lower opportunity cost than others, encouraging specialization and trade.

The interaction of global trade with regional food systems makes supply chains vulnerable to disruptions, but it also increases the diversity and quantity of foods available worldwide.

Political Relationships and Trade Governance

Food distribution networks operate within a political landscape that can either facilitate or restrict the movement of agricultural goods. Government policy shapes access to markets, cost structures, and export potential.

Factors Shaping Political Influence

Several political forces directly affect the structure and direction of food flows:

Tariffs, which raise the cost of imported food and protect domestic agriculture.

Sanctions and trade embargoes, which restrict or block food movement between states.

Subsidies, especially in wealthy countries, which reduce production costs for farmers and influence the competitiveness of exported crops.

Food safety standards, which regulate what can be sold in international markets.

Diplomatic relationships, which affect trade negotiations and long-term agricultural agreements.

These political decisions alter supply availability, market prices, and the geographic pattern of trade connections.

The Geography of Food Distribution

Spatial perspectives help explain why food distribution varies so widely across countries and regions. Distribution networks intersect with uneven economic development, environmental barriers, and historical patterns of trade.

Geographic Variability in Distribution Capacity

Key geographic factors influencing distribution include:

Distance from major markets, which affects transportation costs and delivery times.

Landlocked status, often increasing reliance on neighboring states’ ports and infrastructure.

Climate constraints, which influence what food is produced locally and what must be imported.

Urbanization, which increases demand for high-volume and high-speed distribution systems.

Urban centers often function as distribution hubs, redirecting food across national and international networks.

World Trade Patterns and Food Accessibility

Global trade shapes not only where food moves but also who is able to access it. International food flows contribute to regional food surpluses and deficits, affecting diet quality, price stability, and vulnerability to shocks.

How Trade Affects Food Access

Large import-dependent countries may face food shortages during supply-chain disruptions.

Export-oriented economies risk overreliance on global commodity prices.

Low-income states may struggle to compete with subsidized agricultural exports from wealthier nations.

Trade liberalization can increase food availability but may also displace local farmers.

The spatial patterns of world trade ultimately determine the affordability, diversity, and reliability of food supplies within different regions, demonstrating why political relationships, infrastructure development, and global market dynamics lie at the center of modern food distribution networks.

FAQ

Multinational agribusinesses coordinate production, processing, and distribution across multiple countries, allowing them to control large segments of the global food supply chain.

They influence what crops are grown, where facilities are located, and which transport routes are prioritised. Their financial power can shape global trade patterns by negotiating favourable trade terms and investing in infrastructure in strategic regions.

They may also standardise quality and safety requirements across suppliers, making it easier for food to move internationally but potentially disadvantaging smaller producers who cannot meet these standards.

Even with political stability, countries may lack the physical infrastructure needed to support efficient trade, such as deepwater ports, refrigerated storage, or major highways.

They may also face institutional constraints, including slow customs procedures, corruption, or limited investment capital. These factors reduce reliability and increase the cost of exporting food.

In addition, geographic challenges such as mountainous terrain or long distances to major markets can limit participation even when governance is strong and consistent.

Food distribution networks adapt through a combination of short-term adjustments and longer-term structural changes.

Short-term responses may include rerouting shipments, shifting to alternative suppliers, or increasing use of air freight for high-value perishables.

Long-term changes often involve diversifying supply chains, investing in more resilient infrastructure, or adopting digital tracking systems to improve visibility across stages of transport and storage.

Shipping alliances allow major carriers to share vessels and routes, increasing efficiency and lowering operating costs. This helps maintain stable shipping schedules and reduces the cost of moving food internationally.

Container-sharing agreements expand access to refrigerated containers in particular, which is crucial for transporting perishables such as dairy, meat, and fresh fruit.

However, these arrangements can also create dependencies: disruptions within an alliance may impact many countries at once, particularly those reliant on a limited number of carriers.

Urban areas typically sit at the centre of large distribution hubs, giving them access to frequent shipments, diverse imports, and high-volume retail systems. This leads to greater food variety and more stable prices.

Rural areas may sit far from major logistics corridors, resulting in fewer deliveries, higher transport costs, and more limited selection. Seasonal availability can be more pronounced.

Some rural regions rely heavily on local production, while cities depend largely on national and international supply chains, highlighting a spatial divide in food access shaped by distribution networks.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which political relationships can influence global food distribution networks.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying a relevant political factor (e.g., tariffs, sanctions, trade agreements).

1 mark for describing how this factor affects the movement of agricultural goods.

1 mark for explaining a clear consequence for accessibility, pricing, or trade flows.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Using examples, analyse how differences in infrastructure can lead to uneven participation in global food trade.

Mark scheme:

1 mark for identifying that infrastructure varies between regions or countries.

1 mark for explaining how transportation networks (e.g., ports, roads, railways) affect speed and cost of food movement.

1 mark for linking infrastructure quality to a country’s ability to access international markets.

1 mark for providing at least one real-world example illustrating this variation.

1 mark for analysing a specific impact, such as increased spoilage, reduced competitiveness, or limited export potential.

1 mark for a clear concluding analytical statement on how infrastructure shapes uneven global participation.