AP Syllabus focus:

‘Megacities and metacities are large urban outcomes of urbanization with distinct scale, density, and governance challenges.’

Urbanization has produced extremely large urban settlements whose size, density, and complexity set them apart from typical cities, creating major spatial, economic, and governance implications.

Megacities and Metacities in Global Urban Systems

Megacities and metacities represent the most extreme outcomes of rapid urbanization, reflecting vast populations, intense land-use patterns, and complex administrative demands. Their scale positions them as key nodes in national and global systems.

Defining Megacities

A megacity is generally understood as an urban area with a population exceeding 10 million residents. This threshold distinguishes megacities from smaller metropolitan regions because such large populations generate intensified demands for housing, services, mobility, and governance. Many megacities have developed through sustained rural-to-urban migration, natural population growth, and the consolidation of suburban or peripheral municipalities into a single continuous built-up area.

Megacity: An urban area with more than 10 million inhabitants, characterized by high population density, extensive built-up land, and complex social and economic systems.

Megacities often emerge in countries undergoing rapid industrialization, where economic opportunity draws millions of migrants into expanding metropolitan regions. Their internal structure can reveal stark contrasts between formal and informal development due to uneven access to infrastructure and jobs.

Defining Metacities

A metacity refers to an even larger and more complex urban area—typically defined as urban agglomerations exceeding 20 million residents. Metacities are not simply “larger megacities”; rather, they represent a qualitatively different scale of urban integration where multiple cities, suburbs, and edge settlements merge into massive continuous corridors.

Metacity: A metropolitan region with over 20 million inhabitants, usually consisting of multiple interconnected urban centers forming a vast, continuously built environment.

Metacities reflect advanced stages of urban expansion where administrative boundaries no longer match functional urban regions. As a result, governance becomes fragmented, and infrastructure systems must serve extremely large and dispersed populations.

Distinct Characteristics of Megacities and Metacities

Megacities and metacities differ from smaller cities not only in population size but also in their spatial form, economic roles, and governance challenges. Their unique characteristics help explain why they play outsized roles within national and global systems.

Scale and Spatial Configuration

Their sheer scale influences transportation networks, land-use patterns, and the distribution of economic activity. Key spatial features include:

Extensive built-up areas that stretch across municipal boundaries.

High-density cores contrasted with sprawling peripheral settlements.

Polycentric structures, especially in metacities, where multiple centers operate as major employment and service hubs.

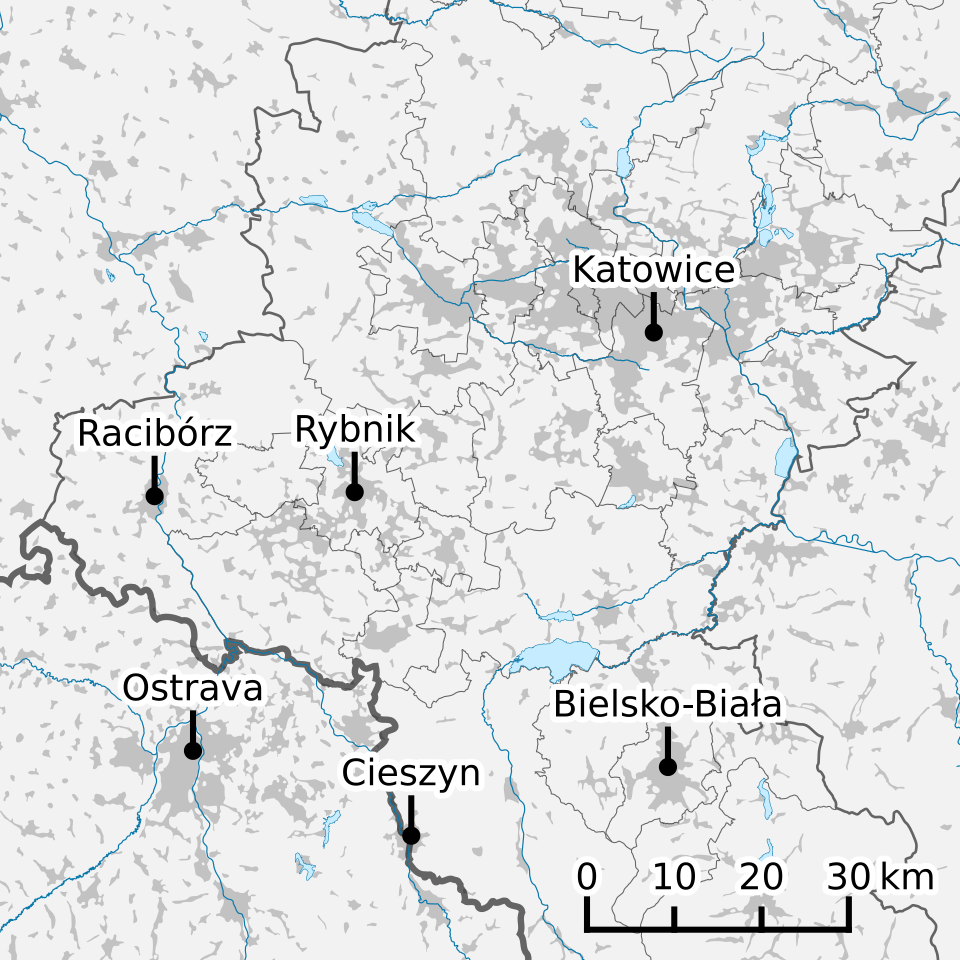

This map illustrates a polycentric metropolitan region in which several urban centers function together as a single system. It supports the concept of polycentricity often seen in metacities, where multiple nuclei serve as employment and service hubs. Specific place names exceed syllabus scope but help visualize the spatial structure. Source.

Because these areas are so large, commuting patterns often extend dozens of miles, contributing to congestion, pollution, and long travel times.

This nighttime NASA image of Tokyo shows continuous illumination across a wide metropolitan region, highlighting the extensive scale and dense built environment characteristic of megacities. Bright light corridors trace major transportation networks, while darker patches reveal parks and water bodies. These features reinforce how spatial form shapes commuting patterns. Source.

Economic Functions and National Influence

Megacities and metacities typically serve as:

National economic engines, concentrating finance, industry, and advanced services.

Hubs of innovation, attracting global talent and investment.

Key nodes in international trade, often anchored by major ports, airports, and logistical infrastructure.

Their economic dominance can produce uneven national development, drawing disproportionate investment and labor into a single huge region.

Demographic and Social Dynamics

The population composition of megacities and metacities is extremely diverse, shaped by:

Mass migration, especially from rural regions seeking employment.

Cultural heterogeneity, often resulting in multilingual, multiethnic communities.

Large youth populations in rapidly urbanizing countries.

Informal housing growth, including slums and squatter settlements when formal housing supply lags behind demand.

Such demographic patterns can heighten inequality and create pressures on public services, schools, and healthcare systems.

Governance and Infrastructure Challenges

The AP specification emphasizes that both megacities and metacities face distinct scale, density, and governance challenges. These challenges arise because traditional municipal systems were not designed to serve such massive urban populations.

Governance Fragmentation

Multiple jurisdictions operate within these giant regions, often with limited coordination. This fragmentation leads to:

Uneven zoning and land-use regulation.

Competing development priorities across local governments.

Limited capacity to manage regionwide transportation, housing, and environmental issues.

Because metacities often encompass several major cities, governance discrepancies become even more pronounced.

Infrastructure Strain

Urban systems must accommodate immense daily demand. Strains commonly appear in:

Transportation, where congestion persists despite heavy investment.

Water and sanitation, as rapid growth outpaces system capacity.

Electricity and energy, with frequent shortages in some regions.

Communication networks, which must expand to serve millions of new users.

Even well-resourced megacities experience infrastructure bottlenecks due to continual population inflows.

Why Megacities and Metacities Matter in Human Geography

Megacities and metacities illustrate the extreme outcomes of global urbanization trends. Their enormous populations, spatial complexity, and governance challenges influence migration patterns, economic development, and national planning priorities. Understanding their characteristics allows geographers to analyze the pressures and opportunities created by rapid urban growth in different world regions.

FAQ

Cities tend to make this transition when multiple urban centres merge into a continuous built-up region due to rapid population growth and spatial expansion.

Key drivers include:

• High rates of rural-to-urban migration

• Increasing economic specialisation that encourages regional clustering

• Expansion of transport corridors linking nearby cities

• Administrative boundary changes that officially join adjacent settlements

Over time, these interconnected cities function as a single metropolitan system, pushing the total population beyond 20 million.

Many Global South countries experience rapid industrialisation, high birth rates, and strong regional migration flows, which accelerate large-scale urban growth.

Limited infrastructure regulation also allows urban areas to expand outward more freely, enabling large agglomerations to form.

Additionally, economic primacy often concentrates investment into one major region, drawing millions into a single metropolitan zone.

These large urban areas often become the central hubs of national transport systems, shaping road, rail, and air infrastructure.

Impacts include:

• High-speed rail and major highways radiating from the core

• Expanded freight infrastructure supporting national and international trade

• Increased pressure on airports and seaports located within or near the region

Their dominant role can lead to uneven transport investment, widening regional disparities.

Metacities typically develop highly specialised and spatially uneven labour markets.

Common patterns include:

• Concentrated high-skilled employment in central business districts

• Clusters of manufacturing or logistics in peripheral zones

• Growth of informal employment where formal job creation cannot keep pace

• Polycentric work patterns as new business districts emerge outside the historic core

These patterns encourage long commuting distances and contribute to reinforced socioeconomic divides.

While both face environmental stress, metacities experience these pressures at a significantly larger scale due to their vast spatial footprint.

Key differences include:

• Greater energy demand across multiple urban centres

• Larger volumes of waste and wastewater to manage

• Increased risk of air pollution spreading across an entire region

• More complex challenges in protecting green space and limiting habitat fragmentation

The environmental impacts extend beyond the immediate urban core, affecting entire regional ecosystems.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which a metacity differs from a megacity.

Mark scheme:

• 1 mark for identifying a correct difference (e.g., population size bracket).

• 1 mark for a clear explanation (e.g., metacities typically exceed 20 million residents, making them larger and more complex).

• 1 additional mark for linking the difference to urban structure or governance (e.g., metacities often form polycentric regions with multiple urban centres, increasing governance challenges).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Analyse two challenges that megacities and metacities face as a result of their size and density.

Mark scheme:

• Up to 2 marks for each challenge identified, described, and explained (e.g., infrastructure strain, governance fragmentation, informal housing growth).

• Up to 2 additional marks for detailed development of either or both challenges, such as explaining underlying causes or using appropriate geographic terminology (e.g., rapid rural-to-urban migration, spatial mismatch, polycentric settlement structure).

• Maximum: 6 marks.