AP Syllabus focus:

‘Suburbanization and decentralization shift jobs and housing outward, changing where people live, work, and travel within a metro area.’

Suburbanization and decentralization transform metropolitan areas by shifting population, employment, and services outward, reshaping daily travel, economic patterns, and the organization of urban spaces today.

Aerial view of suburban sprawl on the outskirts of Adelaide, Australia. The image highlights low-density residential development with detached houses, curving streets, and limited mixed land use. It illustrates how suburbanization consumes more land per person and encourages automobile-based travel, themes discussed in this section. Source.

Understanding Suburbanization and Decentralization

Suburbanization refers to the movement of population from urban cores to surrounding suburbs, while decentralization describes the relocation of economic functions, such as jobs, retail, and services, away from a central business district (CBD). Although related, these processes unfold differently: suburbanization primarily involves residential change, whereas decentralization shifts the spatial distribution of economic activity. Together, they reshape regional spatial patterns and redefine how people interact with the built environment.

Key Drivers of Suburbanization

Transportation Improvements

Advances in transportation infrastructure, especially highways and commuter rail lines, enable residents to live farther from city centers while maintaining access to employment. This outward expansion greatly reduces travel time and increases mobility.

Transportation Infrastructure: The physical systems—such as roads, transit lines, and bridges—that enable movement within and between urban areas.

As suburbs emerge along these corridors, development tends to cluster near major interchange points, accelerating outward population growth.

Housing Demand and Lifestyle Preferences

Many households seek larger homes, lower-density neighborhoods, and perceived improvements in quality of life. Suburbs often offer more green space, newer housing stock, and schools that attract growing families.

Economic Factors

Lower land prices in suburban areas make development more cost-effective for builders and homeowners. Employers also benefit from cheaper land when relocating offices, warehouses, and retail centers to suburban locations.

Decentralization of Urban Functions

Shifting Employment Patterns

Decentralization redistributes employment by moving jobs away from the CBD into suburban office parks, industrial zones, and commercial strips. This shift reduces the dominance of the central city as the primary employment hub. Over time, multiple employment centers can emerge, strengthening suburban economic autonomy.

Central Business District (CBD): The commercial and administrative core of a city, typically containing the highest concentration of offices, services, and transportation connections.

These changes alter commuting patterns by generating more suburb-to-suburb rather than suburb-to-CBD travel.

Retail and Service Dispersion

Retail has decentralized dramatically due to the rise of shopping malls, big-box stores, and more recently, mixed-use lifestyle centers. These facilities rely on large land parcels, car access, and proximity to growing suburban populations. Services such as health care and education follow similar trajectories as providers seek to locate near their key consumer base.

Spatial Patterns Produced by Suburbanization

Low-Density Development

Suburbs typically exhibit low-density residential development, with single-family homes on larger lots. This spatial form consumes large amounts of land and expands metropolitan boundaries.

Polycentric Metropolitan Regions

As economic functions decentralize, metropolitan regions often evolve into polycentric urban forms, with multiple nodes of activity beyond the traditional center. These secondary nodes may include:

Suburban downtowns

Business parks

Major retail corridors

Research and technology districts

Such centers reduce the primacy of the historical urban core and create more complex regional geographies.

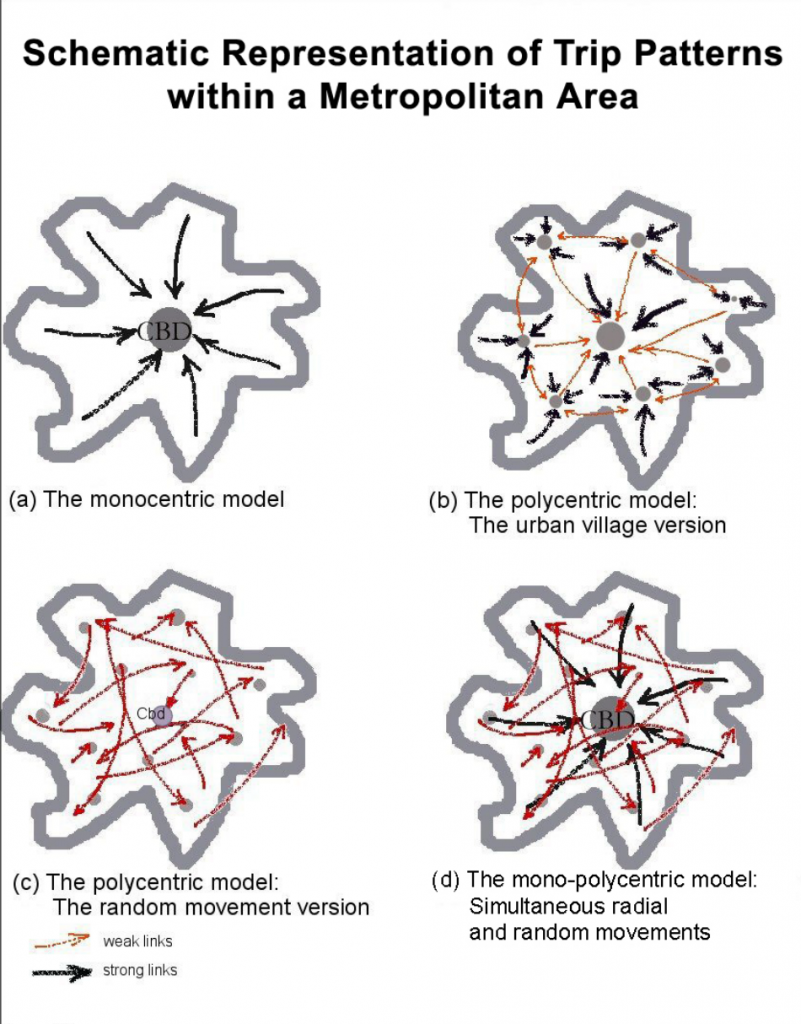

Diagram comparing trip patterns in monocentric and polycentric metropolitan structures. The upper-left panel shows a monocentric city where most trips move radially toward a single CBD, typical before large-scale suburbanization and decentralization. The remaining panels illustrate more complex trip flows across multiple centers; these additional variants extend beyond AP syllabus requirements but help clarify how decentralization reshapes regional travel behavior. Source.

Impacts on Where People Live, Work, and Travel

Changing Residential Patterns

Suburbanization redistributes population across wider areas, often leading to demographic sorting. Suburbs may attract higher-income households, leaving central areas with different socioeconomic profiles. Meanwhile, newer suburbs continue expanding outward, pushing metropolitan boundaries farther from the core.

Transformations in Commuting Behavior

As jobs and housing disperse, commuting flows diversify:

Longer commuting distances emerge as residents move farther from employment centers.

Automobile dependence increases due to limited transit coverage in low-density areas.

Reverse commuting rises as workers travel from central cities to suburban job centers.

Cross-suburban commuting becomes common in highly decentralized metros.

These shifts place pressure on roadway networks and complicate regional transportation planning.

Economic and Social Consequences

Implications for Central Cities

Decentralization can reduce the tax base of the central city as businesses and residents relocate outward. This decline may limit the city's ability to fund infrastructure, public services, and redevelopment efforts. Central areas may also experience uneven investment, with some neighborhoods revitalizing while others face disinvestment.

Metropolitan Inequality

Suburbanization often produces a patchwork of municipalities with varying levels of wealth, services, and capacity. Wealthier suburbs can invest heavily in schools, parks, and infrastructure, while others face fiscal strain. This fragmentation affects regional equity by unevenly distributing opportunities.

Environmental Challenges

Outward expansion increases land consumption, disrupts ecosystems, and heightens reliance on automobiles, contributing to air pollution and higher carbon emissions. Decentralized patterns require more extensive road networks and utility infrastructure, raising long-term environmental and financial costs.

Connections to Broader Urbanization Processes

Suburbanization and decentralization reflect major structural changes in urbanization, including shifts in economic geography, technological advancements, and demographic preferences. By moving people and functions outward, they reshape the spatial organization of metro areas and fundamentally alter how residents live, work, and travel across the urban landscape.

FAQ

Suburban expansion is strongly influenced by zoning regulations that control housing density, land use, and commercial activity. Many suburbs use single-use zoning, which separates residential, commercial, and industrial functions.

This separation reinforces decentralisation by encouraging low-density housing and creating demand for suburban retail and office parks. It also limits mixed-use development, making walking and public transport less viable and increasing reliance on private cars.

Suburbs often attract employers with lower land costs, easier parking, and proximity to skilled labour pools. As employment clusters grow, they develop specialised services, retail centres, and transport links.

Over time, these concentrated advantages can resemble those of a traditional CBD, allowing some suburbs to rival or surpass the central city in job creation and commercial activity.

A polycentric structure emerges when multiple suburban centres attract significant employment and services. This is shaped by factors such as transport access, local government investment, and availability of land for business development.

If several suburbs achieve similar economic strength, the metropolitan region becomes more spatially balanced, with multiple nodes rather than a single dominant core.

Public transport networks are typically radial, designed to funnel passengers into a single CBD. When jobs decentralise, these patterns become inefficient.

To adapt, planners may:

Introduce orbital bus or rail routes

Strengthen cross-suburban connections

Develop transit hubs outside the core

However, decentralised, low-density areas often struggle to support high-frequency services.

Environmental impacts vary depending on the pace and pattern of decentralisation. Rapid outward growth increases land consumption, habitat fragmentation, and car emissions.

Regions that decentralise through large-lot housing or dispersed business parks tend to see greater ecological strain than those focusing growth in compact, well-served suburban centres.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way in which suburbanisation can alter commuting patterns within a metropolitan area.

Mark scheme

1 mark for identifying a valid change in commuting patterns (e.g., increase in suburb-to-suburb commuting, rise in car dependence, longer travel distances).

1 mark for explaining why suburbanisation leads to this change (e.g., jobs relocating outward reduces travel to the CBD).

1 mark for linking the change to decentralisation or the spatial shift of population or employment.

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Using a real or hypothetical example, analyse how the decentralisation of urban functions can reshape economic and social patterns in a metropolitan region.

Mark scheme

1 mark for describing decentralisation of urban functions (e.g., movement of jobs, retail, or services out of the CBD).

1 mark for identifying at least one economic effect (e.g., reduced tax base in the central city, growth of suburban business districts, changes in commercial investment).

1 mark for identifying at least one social effect (e.g., increased socioeconomic sorting, uneven access to services, differences in school or infrastructure quality).

1 mark for providing an example (real or hypothetical) that supports the analysis.

1–2 additional marks for a clear explanation linking decentralisation to broader metropolitan restructuring (e.g., rise of polycentric regions, shifting travel patterns, environmental or equity implications).