AP Syllabus focus:

‘Residential land use changes through cycles of development, and infilling increases density by adding housing within already built-up areas.’

Cycles of Development and Infilling

Urban residential landscapes evolve through repeated phases of construction, decline, reinvestment, and reuse. These cycles shape neighborhood form, density, and long-term patterns of land use.

Urban residential areas change over time as buildings age, populations shift, and land values rise or fall, producing recurring phases of reinvestment, redevelopment, and infilling across the built environment.

Understanding Cycles of Development

Cycles of development describe the repetitive stages through which neighborhoods evolve, often driven by economic, demographic, and policy changes. These cycles help explain why some areas densify, others deteriorate, and still others are redeveloped entirely.

This aerial comparison shows how infill development can dramatically increase building coverage and reduce tree canopy over time in an existing suburb. It illustrates how cycles of development and reinvestment can shift a neighborhood from relatively low density to a tightly packed, highly built-up landscape. The specific location and dates exceed syllabus requirements, but the pattern of change directly supports understanding infilling and its impacts. Source.

Key Stages in Urban Development Cycles

Urban development rarely follows a linear path. Instead, most residential areas move through several identifiable phases:

Initial Construction: Developers build new housing to meet local demand, typically on previously unused or agricultural land at the urban fringe.

Maturation and Stability: As neighborhoods fill in, they reach a period of stability with established infrastructure, services, and community identity.

Aging and Decline: Buildings depreciate, infrastructure ages, and some households move out, often leading to lower property values.

Reinvestment and Renewal: Improvements such as renovations, zoning changes, or new infrastructure encourage renewed interest and investment.

Redevelopment: Older structures may be demolished and replaced with newer, denser, or more profitable land uses.

These shifts reflect broader processes in urban geography, including changing land values, migration patterns, and housing demand.

Factors Influencing Development Cycles

Several forces shape the trajectory and timing of these cycles within cities:

Economic Conditions: Expansions often encourage construction, while recessions may slow renewal or lead to disinvestment.

Demographic Change: Migration, generational turnover, and household-size shifts alter housing needs and preferences.

Planning Policies: Zoning, tax incentives, housing programs, and growth boundaries influence whether neighborhoods redevelop or stagnate.

Infrastructure Investment: New transit lines, highways, parks, and utilities frequently spark reinvestment.

Cultural and Lifestyle Preferences: Consumer demand for walkable neighborhoods or suburban amenities reshapes redevelopment patterns.

Infilling and Its Role in Increasing Urban Density

Infilling refers to the development of vacant or underused parcels within already built-up urban areas. This process is central to how cities increase density without expanding outward.

Infilling: The construction of new buildings on empty or underutilized lots within existing urbanized areas to increase land-use efficiency and density.

A normal sentence is included here to maintain readability following the definition block.

Why Infilling Occurs

Cities pursue infill development for a range of planning, economic, and social reasons:

Efficient Land Use: Using vacant parcels reduces urban sprawl and supports more compact settlement patterns.

Lower Infrastructure Costs: Existing roads, water systems, and transit networks can support new residents without costly expansion.

Housing Supply Pressures: Growing populations and rising housing costs push cities to find new ways to accommodate residents.

Revitalization Goals: Infilling can anchor broader neighborhood renewal efforts by attracting investment and amenities.

Types of Infilling in Residential Areas

Infilling takes various forms that reflect local needs and market conditions:

Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs), such as backyard cottages or garage apartments, which increase small-scale density.

Missing Middle Housing, including duplexes, triplexes, and courtyard apartments, which fit into existing residential blocks while adding units.

Subdivision of Large Lots, allowing more homes to be built where land is underutilized.

Redevelopment of Abandoned or Underused Properties, including former industrial sites, parking lots, or aging single-story structures.

Benefits of Infilling

Infilling can significantly reshape spatial patterns within neighborhoods:

Higher Residential Density: More residents share the same land area, reducing per-person land consumption.

Walkability and Transit Use: Concentrating housing near jobs, services, and transit supports sustainable mobility.

Vibrant Urban Environments: Increased population density can support retail, public spaces, and community facilities.

Environmental Advantages: Compact development reduces emissions from transportation and preserves open land at the urban fringe.

Challenges and Tensions Associated with Infilling

Although infilling supports efficient growth, it can also create tensions in existing communities:

Neighborhood Opposition: Residents may resist new construction due to concerns about congestion, parking, or changing character.

Infrastructure Strain: Older systems may need upgrades to handle higher population density.

Affordability Issues: In some cases, infill development targets higher-income households, raising prices and reducing accessibility.

Regulatory Barriers: Strict zoning rules often limit housing types that support infill opportunities.

Interactions Between Development Cycles and Infilling

Cycles of development and infilling operate together to shape long-term urban change. As buildings age and neighborhoods decline, infill development can introduce renewed investment. At the same time, successful infilling can accelerate redevelopment cycles, attracting new residents, businesses, and infrastructure improvements that transform the character and density of urban areas.

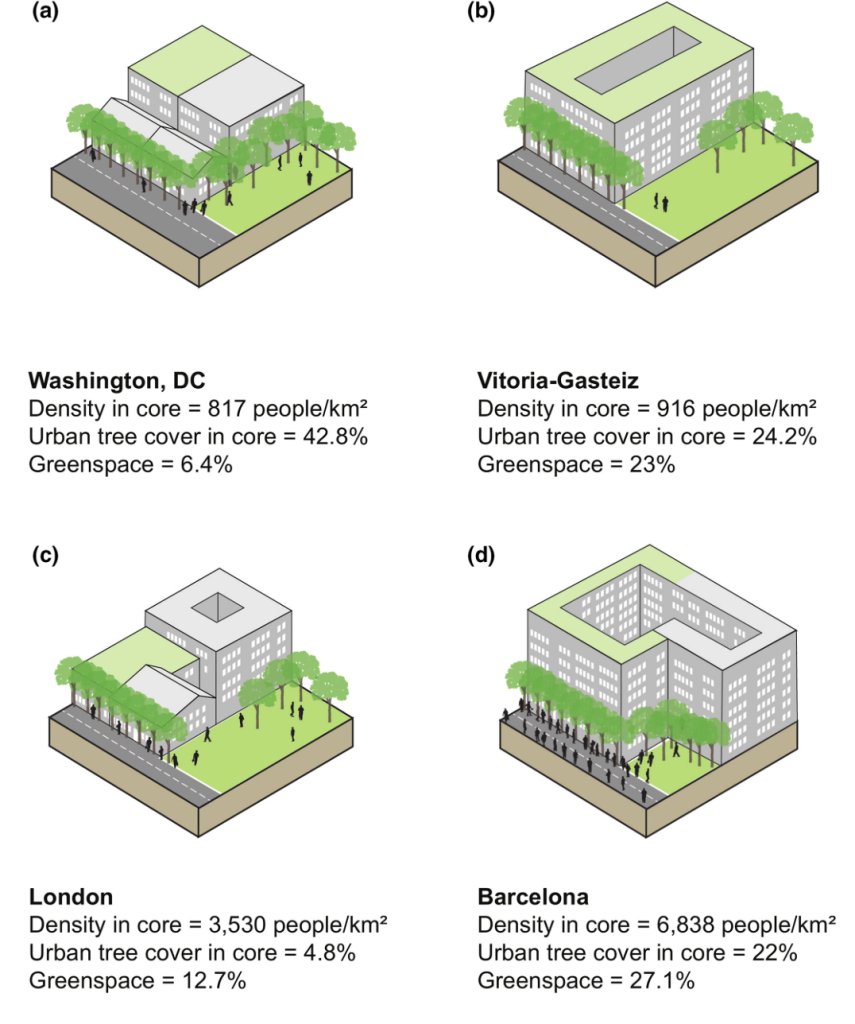

These four diagrams compare different compact building forms, showing how similar levels of density can be paired with varied amounts of tree canopy and greenspace. The image demonstrates that higher density—often achieved through infilling—does not necessarily reduce environmental quality if design is intentional. Numerical values and specific cities exceed syllabus requirements but effectively illustrate how built form and green space can be balanced. Source.

FAQ

Planners evaluate parcels based on factors such as zoning restrictions, access to infrastructure, proximity to services, and environmental constraints. Sites with existing utility connections, good transport access, and minimal ecological sensitivity are usually prioritised.

They also consider community plans, land-value assessments, and the likelihood that redevelopment will align with local housing or sustainability goals.

Neighbourhoods with rising land values, strong transport links, or growing demand often undergo repeated cycles, as reinvestment becomes more profitable.

Areas with weak infrastructure, limited market appeal, or restrictive zoning may remain stable or stagnant, delaying or preventing new development.

Indicators include:

Increased renovation activity

Rising property prices

New planning applications for higher-density housing

Improvements in local services or public transport

These early signals often precede larger-scale redevelopment or infilling.

Infilling may introduce new housing types that attract different income groups, household sizes, or age cohorts, changing the demographic composition.

It can enhance local vitality by increasing footfall and supporting new amenities, but it may also cause tensions if long-term residents feel that neighbourhood character is shifting too quickly.

Small or oddly shaped parcels can make construction costly or technically difficult. Developers may struggle to fit standard housing types onto such sites.

Cities often respond by:

Adapting zoning to allow flexible building forms

Encouraging parcel consolidation

Offering incentives for creative or modular designs

These strategies help make infilling feasible in constrained urban environments.

Practice Questions

Question 1 (1–3 marks)

Explain one way that infilling can change the spatial pattern of a residential neighbourhood.

Mark scheme

Award up to 3 marks:

1 mark for identifying a valid effect of infilling (e.g., increased density, reduced vacant land, more compact form).

1 mark for describing how this effect alters the spatial arrangement of housing or land use (e.g., adding new units within existing blocks).

1 mark for explaining the geographic consequence (e.g., increased walkability, more mixed housing types, reduced pressure for outward expansion).

Question 2 (4–6 marks)

Using your knowledge of urban development cycles, explain how reinvestment and infilling together influence long-term patterns of urban change.

Mark scheme

Award up to 6 marks:

1 mark for describing reinvestment as a stage in the development cycle involving upgrades, renovation, or renewed capital.

1 mark for describing infilling as development on vacant or underused parcels within the built-up area.

1 mark for explaining how reinvestment can attract new demand or alter land values, encouraging redevelopment.

1 mark for explaining how infilling increases density and changes land-use intensity within existing neighbourhoods.

1 mark for linking both processes to broader shifts in the urban landscape (e.g., reduction of sprawl, more mixed-use areas, neighbourhood transformation).

1 mark for a clear, geographically reasoned conclusion connecting cycles of decline and renewal with spatial changes over time.